Challenging Social Norms Around Drinking Water

The Lincoln Institute provides a variety of early- and mid-career fellowship opportunities for researchers. In this series, we follow up with our fellows to learn more about their work.

How do you get people to consider drinking recycled wastewater? That was the challenge Marisa Manheim sought to address as a doctoral student at Arizona State University. With the help of a Babbitt Center Dissertation Fellowship, Manheim worked with 15 tap-water skeptics to conceive and codesign an exhibit aimed at inspiring curiosity about—and perhaps even acceptance of—a concept that many people reflexively reject.

While all water is recycled, in a sense—that’s how the water cycle works—some communities in arid areas, such as Scottsdale, Arizona, have been piloting direct potable reuse (DPR) systems, using advanced purification processes to treat wastewater to standards that exceed those of bottled water. Manheim decided to investigate the public’s response to such programs, bringing theories of embodied cognition to her research and exploring how emotions and bodily sensations contribute to decision-making.

Before pursuing her PhD, Manheim earned a master’s degree in experience design, and worked in corporate design research roles she found less than fulfilling. “A detour into activism” led her into urban agriculture just as the movement gained national momentum in the early 2000s.

Now an assistant professor of environment and sustainability at the University at Buffalo in New York, Manheim continues to take an interdisciplinary approach to her research. In this interview, which has been edited for length and clarity, Manheim explains how good music can influence our choices, why urine makes great fertilizer, and what she’s learned about challenging social norms.

JON GOREY: What was the focus of your dissertation research?

MARISA MANHEIM: I was always trying to answer the question, why is urban agriculture such an amazing launching point for environmental awareness building and intersectional justice and civic participation and all these pieces that have a really hard time getting traction otherwise? And I eventually landed on embodied cognition and activism, which are ideas from cognitive philosophy and psychology about how we process the world around us. It’s very much trying to reintegrate ideas about the body and sensation and social situations into how we conceptualize consciousness and cognition, decision-making, and so forth. I wanted to study something that helped me to explore those ideas further, but didn’t know what it would be.

When I found the concept of recycling wastewater as a drinking water supply, it was basically love at first sight. It’s just such an interesting topic, because it’s about water policy, it’s about food policy, and it’s about novel technologies and the way we tend to be very distrustful or suspicious of them. And because it really comes down to this moment of disgust and reaction, and the way that all manifests, it allowed me to ask a lot of questions about embodied cognition.

The research itself looks at how we are responding to the idea of introducing recycled water into the drinking water supply in central Arizona, how the people in charge of that from a policy and instrumentation side are anticipating and responding to those consumer perceptions, and also how we can apply lessons from design practice and design research to help inform and improve how the decision-making plays out around that topic.

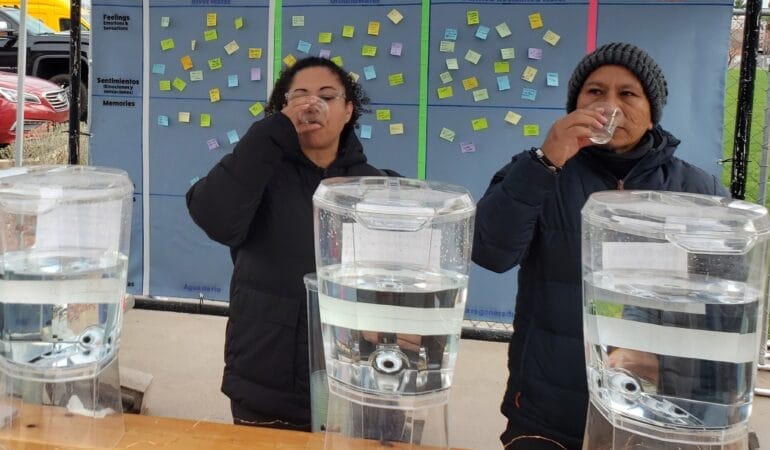

I recruited people who are specifically going out of their way to secure alternative drinking water—so they don’t drink their tap water. I worked very closely with this group of 15 water skeptics to understand and cocreate ways to help other people become curious about the possibilities of incorporating advanced purified water into the drinking water supply . . . and then turned that into an exhibit that engaged 1,100 people in three public festivals.

It starts at the entrance, where there are panels teaching you about water scarcity and the changing climate and the uncertain future of the water supply. Then you go through this inflatable tunnel with this big display about direct potable reuse and how it works. And then you go out of the tunnel, and you’re in this circle where people are standing around drinking water, and there’s lots of fun colors and greenery and music, and you’re invited to sample the water and share your responses to it.

At the entrance to the exhibit, which is called the Future Taste of Water, we had people vote by dropping a marble into one of three water bottles, so they were able to say whether they would support the use of recycled water as a drinking water supply. Something like 77 percent said they wouldn’t support it at the entrance. And then at the exit, they had the same question, and almost everybody supported it.

So the concept is, what works to promote curiosity about a topic with a group of extreme skeptics is highly likely to work with people who are more neutral or who haven’t made up their mind yet.

JG: Many solutions to our biggest challenges hinge on some kind of shift in human behavior. Has your research revealed any strategies that can help reshape people’s attitudes and actions?

MM: Mainly it’s bringing in materiality. It’s very easy to do with recycled water, because we have this artifact, this thing, the water itself. Taking it out of this conceptual, speculative space and making it about something that people can directly interact with completely changes the dynamics.

It’s also social setting; that’s the other ingredient. We did this in a very public space and did things to make it really cool and celebratory—[provided] good music, good aesthetics—and people were almost always surrounded by other people doing the same activity. So there was an opportunity to calibrate your response based on how you think others are responding around you. And that’s the other part of it—we’re constantly calibrating in relationship with the people around us, especially around things that challenge social norms.

Social norms are so important because they reduce the transaction costs of social exchanges. We don’t have to think about, ‘How should I respond to this?’ because social norms have shaped and patterned those responses. When we’re confronted with something and asked to actually slow down and consider responding differently, we can’t rely on those social norms anymore. We have to look around, and think about what we actually feel, the sensations that we’re getting from this beverage, and how we see other people responding.

So if you can make it material for people and if you do it in a social way . . . you can really move things into a space of positivity. . . . My suspicion is that, across almost all of these difficult sustainability transitions that we’re trying to overcome—why is it so hard to get people to ride public transportation? why is it so hard to get people to eat differently, in a more low-carbon way?—if there are opportunities to experience what it would mean on a daily basis, and how it would feel over time, it can provide an experiential foundation for larger changes.

JG: What have you been working on more recently?

MM: I was invited to sign on to a [National Science Foundation] grant as part of the Convergence Accelerator program . . . and the project that I’m a part of is about urine recycling using source separation. So rather than combining feces and urine into a flow and then having to treat them and separate out the things that are valuable for reuse later, the idea is that we can work upstream—literally—and separate the urine and then recycle it as a fertilizer. The piece that I’m responsible for on that project is drawing on my user experience and design research methods, doing a lot of exploratory user and stakeholder interviews and codesign sessions.

If we’re successful in phase two, we’re going to be building out a fully functional mobile demonstration unit with toilets equipped with urinals, female urinals, and potentially a source-separating toilet, where people can go and use the facilities. So it’ll help demystify what it’s going to feel like from a toilet user perspective, but then also you can see how the treatment system works, so it’ll help to demystify what it will look like from an operator’s perspective if you’re a building engineer, architect, or municipal decision-maker.

A big part of the other side of this research, in terms of the design work that I’m involved in, is to work with farmers, extension educators, and other people involved in the agricultural system to inform the product design for the granular fertilizer created by the dehydration process. What is the packaging and labeling? What kind of certification would be necessary? How important is it that it doesn’t have any smell? It has to be a certain size so that it can fit into farm equipment, and obviously the nutrient makeup has to be very consistent and accurately communicated. But there’s a lot more that we don’t really know.

JG: What’s the most surprising thing you’ve found in your research?

MM: Disgust is different when you give people the actual thing instead of the speculative thing. When I worked with this group of water skeptics in the Phoenix region, one person in particular thought that she would never, ever allow her municipal drinking water to pass her lips. They use it for cleaning in her household, and that’s it, because of the taste.

When we gave her the opportunity to try actual DPR water, because we went to the Scottsdale water treatment facility and she got to sample their advanced purified water, she thought it was so good. She had been skeptical about DPR, and she became a huge proponent: “I want that water. Why don’t I have that water now?”

JG: When it comes to your work, what keeps you up at night? And what gives you hope?

MM: The thing that keeps me up at night is the polarization in our society. I see it as a positive feedback loop—the more polarization we have, the more echo chamber and social division, people are only listening to people they already agree with. There’s not this cross-pollination and constructive debate that goes on in a society that isn’t polarized and divided. So it just increases, because you’re surrounded by people who share your viewpoint, and anybody who doesn’t is an “other” and is demonized, or at least not afforded respect.

What I think about a lot is, what can we, as individuals, as universities, as people involved in nonprofit organizations, be doing to help to pull people out of that cycle of polarization and positive reinforcement, and into a space of engagement and interplay and deliberation?

What gives me hope is the work that people are doing and all the intersections I can find. Even though we’re in this moment of crisis and it feels very hopeless, and things are headed in the wrong direction, I don’t know why I’m such an optimist. But I just feel like if enough of us are finding the kernel of truth that we feel motivated by, and if we are doing it in a way that helps us find each other, we can be building alternative futures.

JG: What’s the best book you’ve read lately?

MM: It’s called Disabled Ecologies: Lessons from a Wounded Desert, by Sunaura Taylor, who graduated from the University of Arizona. It’s about the TCE pollution [trichloroethylene, a carcinogen] in South Phoenix related to the aeronautics industry. I picked it up because I’m teaching a Water and Society course this semester, and I was looking for texts that might be worth including. She’s telling a really important story about environmental injustice and persistent pollution, but because she’s a disability scholar, she’s telling it from this embodied perspective that I think is often really missing in these narratives around the environment and injustice.

Forever chemicals and things that are consistently present in our environment—if they’re in our environment, then they’re in our bodies. And this has been borne out by a lot of research, that we are actually part of the disabled ecologies that we’re so concerned about. When we’re trying to restore an ecosystem because it’s an important site for waterfowl or something like that, we’re actually trying to restore our own bodies as well, because we rely on those ecosystems. And so pollutants really help to bring all that into focus. It’s a great way of pulling that all together for people, and I’m definitely going to be using it in my class.

Jon Gorey is a staff writer at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Lead image: Visitors to an interactive Future Taste of Water exhibit sample recycled wastewater. Credit: Marisa Manheim.