COVID-19

This article is reprinted with permission from CityLab, where it originally appeared.

As U.S. states move into the next phase of the coronavirus crisis, they may not be getting all the help they want from the federal government, but they won’t be alone. In at least three parts of the country, states have banded together to coordinate changing public health measures and recovery efforts as they consider timelines for lifting lockdowns, knowing that neither the outbreak nor modern-day regional economies adhere to jurisdictional boundaries set long ago.

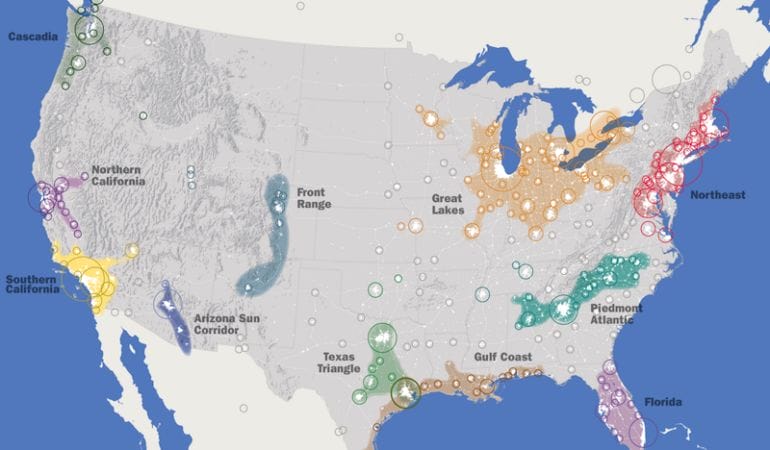

The foundation of these three multistate compacts—seven Northeast states, from Delaware to Massachusetts; the West Coast including California, Oregon, and Washington; and seven Midwestern states radiating around Chicago—is a once little-known planning framework, known as megaregions, that shows just how much big chunks of the country are interlinked.

The pandemic, it turns out, is exactly the kind of massive but geographically clotted crisis that reveals what Europeans have called “territorial cohesion.” Some parts of the country are taking it slow, while others—such as Georgia, Tennessee, and South Carolina—are moving faster to reopen.

Most may think of three basic levels of government—federal, state, and local—but planners have long recognized that much activity actually occurs at the regional scale, across geographically proximate clusters of settlement. People live in one state and commute to a city in another, or live in the city and travel to a second home many miles away if they can.

The megaregion framework has been useful for all kinds of initiatives, whether protecting wilderness and watersheds that similarly cross political jurisdictions, designing transportation policy including inter-city high-speed rail networks, agreeing on carbon emissions reductions, or building more affordable housing across a larger catchment of labor markets (though that last one is very much a work in progress).

States have been working together in some modest ways for years, forming some 200 cross-border compacts or alliances covering everything from infrastructure to regulatory regimes, says Jonathan Barnett, author of Designing the Megaregion: Meeting Urban Challenges at a New Scale. The better-together arrangements can be found at the National Center for Interstate Compacts, part of the Council of State Governments, which provides technical assistance to keep them working. New reasons to collaborate have been steadily emerging, such as the Missouri-Kansas pact limiting tax subsidies as incentives for business relocation.

And now, others who have studied megaregions say, the approach will be well-suited to coordinating reopenings, or continuing closures, as states manage the next phases of the Covid-19 pandemic. If that’s successful, states may use megaregions to make future improvements in housing, transportation, and the environment.

“It’s clear that actions to manage and recover from the pandemic will require regional action, since the virus doesn’t respect arbitrary political boundaries,” says Robert Yaro, former head of the Regional Plan Association and now a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, who is co-authoring a new book on megaregions to be published by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (where I am a senior fellow).

“We can only hope this kind of collaboration will extend to the longer-term steps needed to rebuild the economy—and build the mobility systems and settlement patterns needed to mitigate against future events of this kind,” Yaro says.

The first clue that megaregions might be a useful way of confronting the pandemic emerged as early maps chronicling outbreak patterns mirrored the 11 U.S. megaregions outlined in 2008 by the Regional Plan Association initiative America 2050.

Just as the patterns of contagion mapped mostly along the megaregion categorization, fighting the disease intuitively seemed to require action and coordination across a broader geography than individual cities or states. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo was among the first to propose working together with other states in the Northeast. In the early days of the crisis, there was inter-state tension, as when Rhode Island stopped New Yorkers traveling to summer communities, near the Connecticut border.

In any gradual reopening, it makes all kinds of sense for neighboring states to acknowledge their interconnectedness, says Frederick “Fritz” Steiner, dean of the UPenn Stuart Weitzman School of Design. The closing and reopening of beaches, for example, would benefit from coordination, so there isn’t a patchwork of policies on either side of any state’s borders. Megaregions, which inherently recognize the interconnections in the movement of people emerging from lockdowns, “provide an ideal scale for cooperation in this crisis,” he says.

States in the newly formed alliances have also been sharing protective equipment and other vital supplies. California plans to distribute protective equipment from a ramped-up manufacturing effort throughout the U.S. West, wherever the need is greatest; Montana got more masks from North Dakota than from the national stockpile. Cuomo has proposed a purchasing consortium to avoid a repeat of the “chaos” of 50 states competing for supplies.

It’s important to note that regional interdependency and cooperation does not mean that cities and states don’t need help from the federal government; they clearly do, on such fronts as massive testing and contact-tracing, procuring medical equipment, providing financial relief to people and businesses, keeping beleaguered transit systems financially solvent, and many more pressing needs.

For many it has been gratifying to see how a planning construct could become so useful in this desperate time of need. Planners have been trying to illustrate the advantages of a regional approach for many years, though it has been an uphill battle. Historically, states have often resisted working together—Yaro quips that coordinating efforts of any kind haven’t really been seen since the days of Alexander Hamilton, and even then it was halting. In the 20th century, landscape architect Ian McHarg demonstrated how energy and ecological systems better function across boundaries. For a while, multistate climate pacts, such as the Northeast Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, were de rigeur.

Researchers at America 2050 showed that rather than thinking about a national high-speed rail network, it made more sense to focus on more self-contained chunks of the country—Florida, the Pacific Northwest (or Cascadia), Northern and Southern California, the Texas Triangle, and the Boston-to-Washington corridor. The Federal Railroad Administration has also proposed similar networks for the Midwest, Southeast, and Southwest states, roughly corresponding to the America 2050 map.

In the near-term response to the Covid-19 crisis, any megaregion-scale coordination will initially have a focus on nuts-and-bolts logistics. But the real challenge is what comes after that. Can multiple states continue to think regionally while socioeconomic structures, with all of the built-in inequities that the pandemic has revealed, are refashioned into something more resilient?

Looking ahead, megaregions could become the policy vessel for new realities, including more people working remotely, allowing them to spread out across agglomerated labor and housing markets. “It might actually help mitigate the overconcentration of jobs and population in our largest urban regions—and alleviate the extreme congestion and run-up in housing prices that has undercut the livability and functionality of America’s densest urban places,” Yaro says.

The key to that transformation, he says, will be regional transportation networks that shorten travel times across larger landscapes. That means going back to the notion of better multistate commuter and high-speed rail, at the megaregional scale, like the Regional Plan Association’s T-REX proposal for the tri-state region around New York, the Transit Matters vision for expanded transit all around metro Boston, and an envisioned North Atlantic rail network, including a rerouted Acela through Hartford, for the six New England states and downstate New York. The U.K. is advancing similar strategies with its decision to build HS2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail, underpinning a broader economic development initiative for the north of England.

In a post-pandemic world, better rail networks could speed the economic recovery by providing access to major urban centers by residents of even distant, midsize and legacy cities, bringing in areas across a larger landscape that have been left to decline economically in recent decades.

The deadly coronavirus has laid waste to so much and taken tens of thousands of American lives so far. The rebuilding process, which stands to be a national project not seen since the Great Depression or the aftermath of World War II, might well be more effective if it is structured on a more regional basis. A more megaregional future awaits.

Anthony Flint is a senior fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and a contributing editor to Land Lines.

Image credit: America 2050/Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.