Los suelos de fideicomisos estatales en el oeste intermontañoso de Estados Unidos podrían cumplir un papel importante en el creciente mercado de energía renovable. El Congreso concedió estos territorios, que cubren 14 millones de hectáreas, a los estados tras su incorporación a la Unión, con el fin de respaldar el sistema educativo y otras instituciones públicas. Los administradores de estos suelos de fideicomisos estatales tratan de encontrar maneras innovadoras y sostenibles de arrendar y vender parcelas para generar ingresos, y la energía renovable podría proporcionar una doble ventaja: suministrar energía limpia y sostenible, y al mismo tiempo generar un flujo de ingresos significativo para el beneficio público.

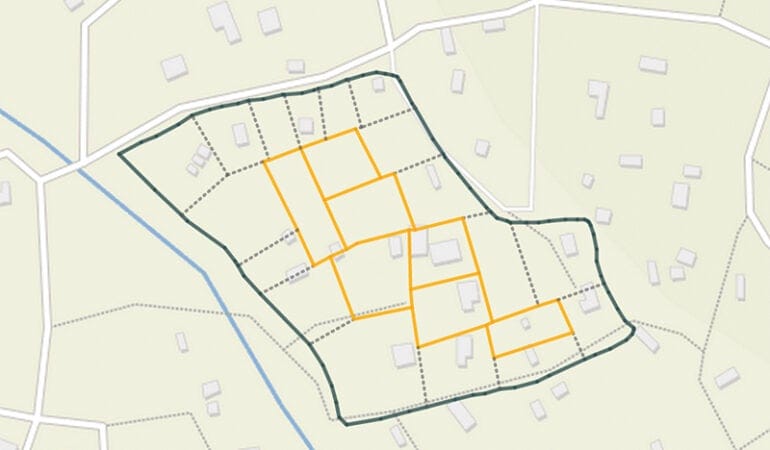

Los siete estados del oeste intermontañoso (Arizona, Idaho, Colorado, Montana, Nuevo México, Utah y Wyoming — ver figura 1) están usando los suelos de fideicomisos estatales para desarrollar energía renovable, con proyectos de energía eólica, solar, geotérmica y biomasa. Sin embargo, la industria no ha alcanzado todavía su pleno potencial. En 2011, la capacidad instalada de producción de energía renovable en fideicomisos estatales era de solo 360 megavatios, lo cual no es siquiera suficiente para alimentar el 2 por ciento de los hogares de la región. Los US$2 millones de ingresos generados por estas fuentes en suelos de fideicomisos estatales son menos del 1 por ciento de los más de US$1000 millones generados anualmente por otros medios (Berry 2013; WSLCA). La energía eólica es la que está experimentando la mayor actividad; todos los estados del oeste intermontañoso han arrendado suelos de fideicomisos estatales para proyectos eólicos, y todos cuentan con parques eólicos operativos. Si bien Arizona, Nuevo México y Utah han arrendado suelos de fideicomisos estatales para operaciones solares, hay solo una planta de generación en producción en el oeste intermontañoso, en Arizona. Sólo Utah tiene una planta geotérmica en suelos de fideicomisos estatales, y no hay ningún estado en la región que cuente con plantas activas de biomasa en suelos de fideicomisos estatales.

Este artículo se enfocará en tres tipos de energía renovable en tres estados distintos: un parque eólico en Montana, proyectos geotérmicos en Utah y generación de energía solar en Arizona, y en las condiciones, legislación y otros factores que han permitido su explotación exitosa. Estos tres ejemplos demuestran que dichos territorios tienen un potencial desaprovechado en su mayor parte para este mercado naciente de energía sostenible, proporcionan oportunidades de aprendizaje en todos los estados y ayudan a satisfacer la creciente demanda de energía renovable.

Parque eólico Judith Gap, Montana

Judith Gap es el único parque eólico operativo en suelos de fideicomisos en el estado de Montana, parcialmente ubicado también en suelos privados, en el centro-este del estado. Cuenta con 90 turbinas en total, cada una con una capacidad de generación de 1,5 megavatios; 13 de ellas están en suelos de fideicomisos estatales, en el borde delantero del parque eólico, con una capacidad total de 19,5 megavatios. El arancel por megavatio de aproximadamente 2,6 por ciento de los ingresos brutos produce alrededor de US$50.000 por año, según Mike Sullivan, del Departamento de Recursos Naturales y Conservación de Montana (DNRC). En el momento de su construcción, se cobró un único arancel por la instalación de US$20.000 (Rodman 2008).

Bob Quinn, el fundador de una compañía local de desarrollo eólico llamada Windpark Solutions, inició el proyecto en el año 2000, cuando le pro-puso la idea a un pequeño grupo que incluyó a representantes de la empresa de servicios públicos local, del Departamento de Calidad Medioambiental de Montana y del DNRC. Quinn dice que la colaboración cercana entre el emprendedor y el personal de estas entidades estatales fue la clave para ubicar con éxito el proyecto en suelos del fideicomiso estatal. El personal estatal también ayudó a Quinn a navegar por los trámites burocráticos, que incluyeron demoras imprevistas en el proceso de licitación requerido por el estado.

Después de realizar estudios preliminares —con un permiso de un año otorgado por medio de una licencia del uso del suelo del DNRC— los emprendedores deben presentar una solicitud ante el DNRC para proseguir con los proyectos de energía. El estado después hace una solicitud de propuestas. Los candidatos que tienen una licencia del uso del suelo no reciben tratamiento preferencial. Después de haber identificado a un candidato competente, éste tiene que realizar un estudio medioambiental, llegar a un acuerdo de compra de energía con una empresa de servicios públicos y determinar la factibilidad económica de su proyecto antes de firmar un contrato de arriendo con el DNRC. En la actualidad, los aranceles de licencias nuevas para el uso del suelo son generalmente de US$2 por acre (equivalente a 0,40 hectáreas) al año. Los costos de los acuerdos de arriendo para nuevos proyectos eólicos incluyen un arancel de instalación único de US$1.500 a US$2.500 por megavatio de capacidad instalada, y aranceles anuales del 3 por ciento de los ingresos brutos anuales o un mínimo de US$3.000 por cada megavatio de capacidad instalada (Rodman 2008, Billings Gazette 2010).

Estructura de arriendo y aranceles

Cada estado tiene un sistema de arriendo distinto para los proyectos de energía renovable en suelos de fideicomisos estatales, pero todos siguen un patrón similar. El proceso comienza en general con un arriendo de corto plazo para planificación, que permite la realización de estudios meteorológicos y de exploración. A continuación está la fase de construcción, seguida de un arriendo de largo plazo para la producción. Los pagos a la agencia que administra los suelos de fideicomisos estatales incluyen en general un monto por hectárea durante la etapa de planificación, que puede continuar durante la etapa de producción. Hay cargos adicionales por instalación de equipos, como torres meteorológicas, turbinas eólicas, colectores de luz solar, estructuras y alguna otra infraestructura. Durante la etapa de producción, el arancel se basa generalmente en la capacidad instalada o en los ingresos brutos de la planta de generación.

Desde que se completó el parque de Judith Gap en 2005, se han propuesto varios parques eólicos en suelos de fideicomisos estatales en Montana, pero ninguno de ellos ha alcanzado todavía la fase de producción. Entre éstos se incluye el proyecto de energía eólica de Springdale, un parque eólico de 80 megavatios compuesto por 44 turbinas, 8 de las cuales estarían en suelos de fideicomisos estatales. El DNRC también ha arrendado 1.200 hectáreas cerca de Martinsdale a Horizon Wind Energy para un parque eólico de 27 turbinas, de las cuales de 7 a 15 estarían en suelos de fideicomisos estatales. El parque eólico de Martinsdale podría ampliarse en el futuro a 100 turbinas (Montana DNRC).

Para que los suelos de fideicomisos estatales sean más atractivos para estos y otros emprendedores de energía renovable, el DNRC debería simplificar el proceso. Los emprendedores que han trabajado en los suelos de fideicomisos estatales en Montana han citado problemas de demoras, financiamiento, mitigación medioambiental, falta de cooperación de las empresas de servicios públicos y transmisión (Rodman 2008). Según Quinn, Judith Gap tuvo éxito en parte debido a la dedicación y colaboración cercana entre el personal estatal y el emprendedor de energía. En el futuro, el DNRC quizá tenga que asignar personal dedicado a proyectos de energía renovable para ayudar a los emprendedores con este proceso. El DNRC también podría atraer proyectos otorgando a los licenciatarios del uso del suelo un estado preferencial en el proceso de licitación y acelerando dicho proceso. Quinn señala que el sistema podría mejorar si se evaluaran las ofertas de acuerdo a la prestación, en vez de tener en cuenta solamente el precio.

Energía geotérmica, Utah

La energía geotérmica es una fuente potencial de energía constante, al compensar las fluctuaciones de las energías renovables intermitentes como la eólica o solar. No obstante, también es técnicamente compleja y cara — y por tanto inusual en los suelos de fideicomisos estatales del oeste intermontañoso. En la actualidad, Utah es el único estado de la región con plantas geotérmicas activas en suelos de fideicomisos estatales. Por superficie, la geotérmica es la mayor fuente de energía renovable en Utah, con aproximadamente 40.000 hectáreas situadas en suelos de fideicomisos estatales. En la actualidad hay dos plantas de energía geotérmica en producción que generan ingresos de entre US$200.000 y US$300.000 al año. Para los proyectos geotérmicos, la Administración de Suelos de fideicomisos estatales e Institucionales (SITLA), que administra los suelos de fideicomisos estatales en Utah, cobra un 2,25 por ciento de las ventas de electricidad durante los primeros 5 a 10 años y un 3,5 por ciento de ahí en adelante.

La planta de 34 megavatios de PacifiCorp en Blundell, en territorio de propiedad mixta privada, federal y estatal, fue la primera construida en el estado en 1984. Blundell explota una reserva subterránea que se encuentra a 1.000 metros de profundidad, a una temperatura de más de 260° C y una presión de 34 atmósferas (500 psi). Se perfora un pozo para que el agua caliente y de alta presión suba a la superficie e impulse una turbina de vapor. La planta de Blundell tiene dos unidades, una de 23 megavatios, construida en 1984, y otra de 11 megavatios, completada en 2007.

La planta más reciente de Raser en el condado de Beaver ha tenido menos éxito. Raser pensó instalar originalmente una planta de 15 megavatios usando una tecnología modular más moderna producida por United Technologies, dijo John Andrews, subdirector de SITLA. La empresa intentó reducir el costo y el tiempo de desarrollo explorando el recurso geotérmico al mismo tiempo que construía la planta de generación, en vez de perforar primero los pozos geotérmicos y después construir la planta. Desafortunadamente, el recurso geotérmico fue más escaso de lo previsto y no pudo soportar la potencia nominal de 15 megavatios. Con ingresos limitados, Raser no pudo cubrir sus deudas y se declaró en quiebra en 2011. La planta sigue funcionando con una capacidad limitada (Oberbeck 2009).

La experiencia de Raser demuestra que los costos del desarrollo geotérmico siguen siendo desa-lentadores, y que vale la pena analizar previamente en profundidad las características del recurso geotérmico disponible antes de construir las plantas de generación, si bien este paso adicional es costoso y demora tiempo. Los futuros avances tecnológicos pueden ayudar a reducir el costo y el tiempo necesario para el desarrollo geotérmico, pero dado el estado actual de la tecnología, los proyectos geotérmicos exigen todavía importantes inversiones iniciales.

SITLA es la entidad encargada de dar respuesta a los proyectos de desarrollo de energía renovable a medida que se reciben; también puede ofrecer suelos en arriendo mediante solicitud de ofertas o proceso de licitación en pliego cerrado (Rodman 2008). El estado ha hecho un mapa de zonas de energía renovable, pero la tarea de encontrar los lugares y proponer proyectos de energía renovable recae sobre los emprendedores.

Utah también enfrenta otras dificultades para todas las formas de desarrollo de energía renovable en suelos de fideicomisos. Debido a la alta proporción y el patrón de distribución de territorios federales, las agencias nacionales a veces son las que toman la iniciativa en proyectos de desarrollo de energía. Según Andrews, la ausencia de un estándar de cartera de energía renovable (Renewable Portfolio Standard, o RPS) en Utah es otra desventaja, porque las empresas locales de servicios públicos carecen de un mandato estatal para suministrar energía renovable.

Aun sin un RPS, sin embargo, Utah está bien situado geográficamente para exportar energía a otros estados, particularmente a los centros de población en la costa oeste. Aunque la transmisión de energía puede constituir un impedimento en algunas partes del estado, existe en la actualidad capacidad de transmisión entre Utah y el sur de California. Más aún, los emprendedores pueden aprovechar una serie de recursos renovables: eólico, solar y geotérmico. SITLA podría comercializar los suelos de fideicomiso en zonas de energía renovable a emprendedores potenciales, ofreciendo aranceles reducidos para proyectos en dichas zonas.

Desarrollos solares en Arizona

Incluso en Arizona, el estado más soleado de los EE.UU., según el Servicio Meteorológico Nacional, la industria solar enfrenta varios obstáculos en los suelos de fideicomisos estatales. La única planta solar activa en suelos de fideicomisos estatales, la planta solar de Foothills, se inauguró en 160 hectáreas del condado de Yuma en abril de 2013, con la puesta en marcha de 17 megavatios. 18 megavatios adicionales entrarán en operación en diciembre de 2013. Cuando se encuentre plenamente operativa, la planta dará servicio a 9.000 clientes. El contrato de arriendo de 35 años generará US$10 millones para los beneficiarios de los suelos de fideicomisos estatales, y la mayor parte de este dinero se destinará a la educación pública.

El desarrollo lento de la industria solar en de suelos de fideicomisos refleja una tendencia más amplia a nivel nacional. En 2010, sólo el 0,03 por ciento de la energía del país provino de proyectos solares, mientras que el 2,3 por ciento fue generado por el viento (www.eia.gov). Los proyectos solares en general exigen el uso exclusivo de un sitio, lo cual genera una desventaja más grande aún en los suelos de fideicomisos estatales, donde ya hay muchas otras hectáreas arrendadas para agricul-tura, pastoreo o producción de petróleo y gas. Los proyectos eólicos, en contraste, pueden coexistir con otros usos del suelo. Los proyectos solares también requieren mucha superficie, hasta 5 hectáreas por megavatio (Culp y Gibbons 2010), mientras que las plantas eólicas tienen una huella relativamente pequeña. Y, aun cuando los precios están cayendo, las plantas de generación solar pueden ser muy caras.

A pesar de estas desventajas, hay siempre maneras en que se puede adaptar el desarrollo solar a los suelos de fideicomisos estatales. Para empezar, estos territorios no pagan impuestos ni tienen deudas; como no tienen la misma carga financiera que los propietarios privados, las agencias que administran los suelos de fideicomisos tienen una ventaja para ubicar y mantener proyectos de energía renovable. Algunos emprendedores solares encuentran atractivos los suelos de fideicomisos estatales porque permiten la utilización de grandes superficies por parte de un solo propietario. La generación solar también se adapta bien a sitios que sufrieron perturbaciones previamente, como viejos rellenos sanitarios y áreas agrícolas abandonadas, que pueden incluir los suelos de fideicomisos. Cerca de las zonas urbanas, los suelos de fideicomisos estatales que están en reserva para emprendimientos futuros se podrían usar en el ínterin para generación solar; cuando los contratos de arriendo venzan, el suelo se podría usar para emprendimientos urbanos (Culp y Gibbons 2010).

Un estándar de energía renovable estatal e incentivos tributarios también podrían alentar el desarrollo solar. Algunos estados ofrecen créditos tributarios de hasta el 25 por ciento para inversiones, exenciones del impuesto sobre la propiedad, y contratos de compra con términos estándar para energía solar, garantizando un mercado a largo plazo para la generación solar.

El Departamento de Suelos Estatales de Arizona (ASLD), uno de los terratenientes más grandes del estado, con varias parcelas consolidadas de gran tamaño, se podría posicionar como socio atractivo para la industria de energía renovable (Wadsack 2009). El ASLD está dando pasos en la dirección correcta, desarrollando un sistema de mapas de energía renovable con SIG a fin de analizar la adecuación general de los suelos de fideicomisos estatales de energía renovable para la producción solar, evitando al mismo tiempo las áreas de hábitat de vida silvestre y de preservación del desierto, y reduciendo la distancia a caminos, líneas de transmisión y centros de demanda. Pero tiene que seguir avanzando y comercializar las áreas más adecuadas para energía renovable (Culp y Gibbons 2010) y facilitar el proceso a los emprendedores, que pueden desalentarse a causa de las complejas estructuras de arriendo, los requisitos de subasta pública y las exigencias de análisis medioambiental y cultural (Wadsack 2009). Cuanta más capacidad pueda construir el Departamento para ayudar a los emprendedores en este proceso, más podría florecer la industria de energía renovable en los suelos de fideicomisos estatales. Por ejemplo, el departamento podría ofrecer contratos de arriendo de largo plazo, acelerar la venta de suelos y desarrollar un sistema de arriendo de costo reducido con participación en los ingresos, diseñado específicamente para el desarrollo de energía renovable.

Recomendaciones generales para Montana, Utah y Arizona

El arriendo para energía renovable en los suelos de fideicomisos estatales es complicado. Cada estado posee un conjunto singular de circunstancias políticas, medioambientales y económicas que hace difícil establecer un método óptimo para todos. No obstante, los logros, problemas y soluciones detalladas en los ejemplos anteriores brindan algunas recomendaciones generales para alcanzar el éxito.

A nivel de la agencia que administra el fideicomiso de suelos estatales:

A nivel estatal:

Las políticas federales cumplen también un papel importante. En particular, los créditos tributarios a la producción han estimulado el desarrollo de energía renovable en las últimas décadas. Del mismo modo los créditos tributarios federales a la inversión en energía renovable, que proporcionan a los emprendedores un crédito tributario durante las fases de planificación y construcción, han ayudado al crecimiento de la industria de energía renovable en los últimos, aun cuando la economía nacional estaba en recesión. Finalmente, se han presentado varias propuestas para un estándar federal de cartera de energía renovable, si bien los investigadores no se ponen de acuerdo sobre si este tipo de política podría interferir con las políticas de RPS a nivel estatal, que han demostrado ser extremadamente efectivas.

La energía renovable ofrece a los administra-dores de suelos de fideicomisos estatales una oportunidad para diversificar sus ingresos y beneficiar el bien común. En su mayoría, los proyectos eólicos y de transmisión se pueden ubicar en terrenos que ya se han arrendado para pastoreo, agricultura, petróleo y gas. Los proyectos solares podrían tener su mayor potencial en áreas previamente alteradas o en zonas con escaso valor alternativo. Donde haya recursos geotérmicos disponibles, se podrá generar energía en forma constante para compensar las fuentes de energía intermitentes, como el viento y el sol. Los avances técnicos podrían ayudar a reducir los precios de la energía renovable, sobre todo la energía solar, geotérmica y de biomasa. A medida que nuestras demandas de energía van creciendo, los suelos de fideicomisos estatales están en condiciones de desempeñar un papel importante en el crecimiento de la industria de energía renovable.

Este artículo fue adaptado del documento de trabajo del Instituto Lincoln “Leasing Renewable Energy on State Trust Lands” (Arriendo de energía renovable en suelos de fideicomisos estatales), disponible en línea en: www.lincolninst.edu/pubs/dl/2192_1518_Berry_WP12AB1.pdf.

Sobre el autor

Alison Berry es la especialista de energía y economía en el Sonoran Institute, donde su trabajo se concentra en temas del uso del suelo en el cambiante Oeste de los EE.UU. Tiene una licenciatura en Biología por la Universidad de Vermont y una maestría en Silvicultura por la Universidad de Montana. Sus artículos han sido publicados en el Wall Street Journal, el Journal of Forestry, y el Western Journal of Applied Forestry, entre otras publicaciones. Contacto: aberry@sonoraninstitute.org.

Recursos

Berry, Jason, David Hurlbut, Richard Simon, Joseph Moore y Robert Blackett. 2009. Utah Renewable Energy Zones Task Force Phase I Report. http://www.energy.utah.gov/renewable_energy/docs/mp-09-1low.pdf.

Billings Gazette. 2010. Wind farm developers eye school trust land. April 22. http://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/montana/article_14bfb038-4e0a-11df-bc99-001cc4c002e0.html.

Bureau of Land Management. 2011. Restoration Design Energy Project. http://www.blm.gov/az/st/en/prog/energy/arra_solar.html.

Culp, Peter y Jocelyn Gibbons. 2010. Strategies for Renewable Energy Projects on Arizona’s State Trust Lands. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper WP11PC2. https://www.lincolninst.edu/pubs/dl/1984_1306_CulpGibbon%20Final.pdf.

Montana Department of Natural Resources. 2011. Montana’s Trust Lands. Presented at the Western States Land Commissioners Association annual meeting. Online: http://www.glo.texas.gov/wslca/pdf/state-reports-2011/wslca-presentation-mt-2011.pdf accessed November 23, 2011.

Oberbeck, Steven. 2009. Utah geothermal plant runs into cold-water problems. Salt Lake Tribune. September 17. And Bathon, Michael. 2011. Utah’s Raser Technologies files Chapter 11. Salt Lake Tribune. May 2.

Rodman, Nancy Welch. 2008. Wind, wave/tidal, and in-river flow energy: A review of the decision framework of state land management agencies. Prepared for the Western States Land Commissioners Association. http://www.glo.texas.gov/wslca/pdf/wind_wave_tidal_river.pdf.

Wadsack, Karin. 2009 Arizona Wind Development Status Report. Arizona Corporation Commission.

Una versión más actualizada de este artículo está disponible como parte del capítulo 3 del libro Perspectivas urbanas: Temas críticos en políticas de suelo de América Latina.

El caso de Mexicali, capital del estado fronterizo de Baja California (México), es ejemplo destacado de una reforma exitosa hecha al sistema fiscal inmobiliario en la década de 1990. En apenas unos cuantos años, el gobierno municipal pudo aumentar las entradas provenientes del gravamen inmobiliario, así como también fortalecer sus finanzas y modernizar sus sistemas catastrales y de recaudación. Más aún, Mexicali llevó a cabo esta reforma adoptando un sistema de tributación sobre el valor de la tierra nunca antes aplicado en México, y los cambios contaron con la aceptación de la ciudadanía. A pesar de los problemas y errores surgidos a lo largo del proceso, esta experiencia ofrece lecciones provechosas a entidades interesadas en emprender reformas futuras del sistema fiscal inmobiliario, en México u otros países.

Consideraciones económicas, políticas y técnicas

Emprender una reforma del sistema fiscal sobre la propiedad inmobiliaria no parecía ser tarea fácil ni en Mexicali ni en ninguna parte de México. Desde 1983, el gobierno local ha tenido la responsabilidad de fijar y recaudar los gravámenes a la propiedad inmobiliaria, aunque ciertas responsabilidades aún recaen sobre las autoridades estatales. A lo largo de la década de 1980, tanto la recaudación del gravamen inmobiliario como los ingresos municipales en general sufrieron una caída estrepitosa causada por la combinación de una fuerte espiral inflacionaria, la recesión económica, la falta de interés político , y la insuficiente experiencia y capacidad administrativa de los gobiernos municipales, quienes preferían depender de fuentes de participación en los ingresos fiscales.

Como resultado de las mejoras en el rendimiento macroeconómico de la nación, a inicios de los noventa se dieron las condiciones para un cambio en la situación, aunque ciertos factores políticos y técnicos redujeron los incentivos para que muchos gobiernos estatales y municipales iniciaran una reforma fiscal. No obstante, el gobierno federal de Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1989-1994) se lanzó a mejorar las finanzas municipales mediante un programa de modernización catastral impulsado por el Banco Nacional de Obras y Servicios (BANOBRAS), un banco de desarrollo público.

Incluso antes de que este programa y otras políticas nacionales comenzaran a influir sobre los gobiernos municipales y estatales, Mexicali tomó la delantera en la reforma al sistema fiscal. En 1989 el presidente municipal electo, Milton Castellanos Gout, entendió la importancia de fortalecer las finanzas municipales y comenzó a trabajar para elevar los ingresos tributarios al comienzo de su mandato. Para actualizar los valores catastrales, contrató los servicios de una empresa privada dirigida por Sergio Flores Peña, graduado en planificación regional y urbana en la Universidad de California en Berkeley. Flores propuso al nuevo presidente abandonar el sistema impositivo de base mixta (construcciones y suelo) y adoptar uno basado exclusivamente en el valor del suelo, y diseñar un modelo matemático para calcular los precios del suelo.

Más que atracción por las creencias teóricas o ideológicas asociadas con un impuesto sobre el valor de la tierra, Castellanos sentía que dicho gravamen era una manera fácil y rápida de aumentar la recaudación de ingresos, y asumió el riesgo político de proponer un Comité Municipal de Catastro integrado por organizaciones de bienes raíces, organizaciones profesionales y representantes de la ciudadanía.

Los resultados fueron espectaculares desde dos puntos de vista: primero que todo, el nuevo impuesto elevó los ingresos rápidamente (ver fig.1); y segundo, no hubo oposición ni política ni legal en contra de las medidas fiscales por parte de los contribuyentes. El aumento de ingresos por concepto de mayores gravámenes a la propiedad inmobiliaria y ventas de bienes raíces ¾la mayor fuente de ingresos municipales¾ permitió al presidente poner en marcha un importante programa de servicios públicos. No obstante, al año siguiente Castellanos decidió disminuir el control fiscal y no actualizar los valores del suelo, lo cual llevó al abandono del modelo matemático que había sido creado originalmente para ese propósito.

Tanto el Comité Municipal de Catastro como los funcionarios gubernamentales que estaban a cargo de la oficina de valuaciones y de catastro se opusieron a fijar los nuevos valores catastrales. Estas personas carecían de la capacidad técnica para manipular el modelo y temían disminuir su poder y control si dejaban el asunto en manos de la empresa consultora privada. Como resultado, se abandonó el modelo matemático y en lo sucesivo se definieron los valores del suelo mediante un proceso de negociación y convenios entre las autoridades locales, los representantes electos y el comité.No obstante, no se modificó el sistema de cálculo del valor catastral de base suelo.

Al mismo tiempo, el gobierno de Castellanos lanzó un programa de modernización catastral con recursos financieros del gobierno federal. Sin embargo, dado que el presidente consideraba que ya se había logrado el objetivo principal de aumentar los ingresos, relegó a un segundo plano la modernización del sistema catastral y no se pudo lograr el mismo éxito.

En las administraciones subsiguientes varió la política de recaudaciones tributarias y modernización catastral. El próximo presidente, Francisco Pérez Tejeda (1992-1995), era miembro del mismo partido político (Partido Revolucionario Institucional, PRI). Durante su primer año de gobierno hubo un descenso en los ingresos por gravámenes a la propiedad inmobiliaria, y los impuestos aumentaron sólo al final de su mandato. Pérez abandonó el programa de modernización catastral, pero mantuvo el sistema de tributación sobre el valor de la tierra.

La siguiente administración estuvo presidida por Eugenio Elourdy (1995-1998), miembro del Partido de Acción Nacional (PAN) quien fue el primer líder de un partido de oposición en Mexicali, aun cuando un miembro del PAN había gobernado en el ámbito estatal de 1989 a 1994. En la administración de Elourdy se actualizaron los valores catastrales, hubo un crecimiento continuo de la recaudación del gravamen inmobiliario y se volvió a implementar la modernización catastral. La actual administración de Víctor Hermosillo (1999-2001) está continuando con la reforma catastral.

Evaluación de la experiencia de Mexicali

Sin duda alguna, el proceso de reforma fiscal ha convertido la recaudación del gravamen inmobiliario en la más rápida e importante fuente financiera de los gobiernos municipales. Esta recaudación representa actualmente más del 50 % de los ingresos municipales locales. El rendimiento relativo del gravamen inmobiliario respecto a los ingresos totales de Mexicali está muy por encima de los promedios estatales y nacionales (15,3 % en 1995, comparado con 8,4 % para el estado y 10,3 % para todo el país). Los funcionarios del gobierno municipal que están a cargo de los sistemas catastrales y de valuación están bien preparados, poseen el conocimiento técnico y están conscientes de la necesidad de conducir reformas permanentes dentro del sistema. El ejemplo de Mexicali ha sido ya imitado en el resto del estado de Baja California y en el estado vecino de Baja California Sur.

El caso de Mexicali ofrece lecciones importantes. La primera de todas es que los gravámenes a la propiedad inmobiliaria son fundamentales para fortalecer los gobiernos municipales, no sólo para recaudar ingresos suficientes para el desarrollo urbano, sino también para proporcionar a los funcionarios gubernamentales las destrezas necesarias que les permitan organizar el sistema fiscal de una forma exitosa, legítima y transparente ante los ojos de la ciudadanía.

En segundo lugar, una reforma al sistema fiscal sobre la propiedad inmobiliaria es algo que requiere visión, liderazgo, y sobretodo, voluntad política y compromiso por parte de los dirigentes. Asimismo, el éxito de una reforma que vaya acompañada por un aumento de impuestos, requiere también contar con una base técnica sólida y con aceptación por parte del público.

En tercer lugar, se demostró la enorme utilidad del impuesto sobre el valor de la tierra para lograr una reforma exitosa en una etapa temprana. Claramente, la razón fundamental para adoptar dicho sistema tuvo que ver más con un abordaje pragmático que con bases o posiciones teóricas sobre diferentes filosofías. Sin embargo, ello no debe impedir que los funcionarios gubernamentales, asesores, expertos y el público en general emprendan un análisis cuidadoso de las diversas consecuencias de tal abordaje en términos de eficiencia económica, justicia y equidad fiscal.

Aunque el sistema de impuesto sobre el valor de la tierra tuvo éxito en el caso de Mexicali, no debe ser visto como una panacea aplicable en todas las situaciones. Es importante reconocer que el impuesto sería muy poco útil sin otras medidas que deben ser consideradas como parte de la reforma al sistema fiscal sobre la propiedad inmobiliaria, tales como modernización catastral, transparencia en la fijación de tasas impositivas y participación del público. Por último, es importante ver las reformas al sistema fiscal sobre la propiedad inmobiliaria en otras ciudades del mundo como procesos integrales, y no como “éxitos” o “fracasos”. Tal como el caso de Mexicali, son experiencias que combinan aciertos y desaciertos. Lejos de ser ejemplo de una reforma perfecta, Mexicali es una buena experiencia de aprendizaje porque demuestra que los cambios sí son posibles incluso cuando no lo parecen.

Manuel Perló Cohen es investigador del Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Para este estudio recibió apoyo del Instituto Lincoln. Perló Cohen ha participado en numerosos cursos y seminarios patrocinados por el instituto en varias ciudades de América Latina.

Figura 1. Recaudación del gravamen inmobiliario en Mexicali, 1984-1998

Fuente: Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público. Tesorería del XVI Ayuntamiento de Mexicali. Instituto Nacional de Estadistica, Geografia e Informatica.

Una versión más actualizada de este artículo está disponible como parte del capítulo 3 del libro Perspectivas urbanas: Temas críticos en políticas de suelo de América Latina.

América Latina es una región de marcados contrastes en cuanto al uso del suelo: la extensa selva del Amazonas y crecientes áreas de deforestación, grandes regiones despobladas y enormes concentraciones urbanas, la coexistencia de la riqueza y la pobreza en los mismos vecindarios. Muchos de estos contrastes derivan de las políticas de suelos establecidas por intereses poderosos que se han perpetuado gracias a registros desactualizados o distorsionados. Esta herencia es parte del proceso de colonización de la región que se ha caracterizado por la explotación y la ocupación de tierras a cualquier precio.

El primer sistema de información para el registro de parcelas de tierra en América Latina lo estableció en 1824 la Comisión Topográfica en la Provincia de Buenos Aires de la República Argentina. Las oficinas de catastro territorial en toda la región actualmente manejan sistemas de información sobre suelos públicos en los que se registran mapas y datos sobre los terrenos sujetos a impuestos y se otorgan derechos a los propietarios u ocupantes de la tierra.

¿Qué es un catastro?

Un catastro moderno es un sistema integrado de bases de datos que reúne la información sobre el registro y la propiedad del suelo, características físicas, modelo econométrico para la valoración de propiedades, zonificación, sistemas de información geográfica, transporte y datos ambientales, socioeconómicos y demográficos. Dichos catastros representan una herramienta holística de planificación que puede usarse a nivel local, regional y nacional con la finalidad de abordar problemas como el desarrollo económico, la propagación urbana, la erradicación de la pobreza, las políticas de suelo y el desarrollo comunitario sostenible.

Los primeros registros de agrimensura de propiedades en el antiguo Egipto utilizaron la ciencia de la geometría para medir las distancias. Más tarde los catastros europeos siguieron este modelo antiguo hasta que nuevos conocimientos dieron lugar a sistemas más integrados que podían usarse para fines fiscales, como la valoración, la tributación y las transferencias legales, así como la gestión del suelo y la planificación urbana. En los Estados Unidos no existe un sistema nacional de catastro, pero los procesos municipales semejantes son reflejo de la política y el protocolo de los programas internacionales de catastro.

La Federación Internacional de Agrimensores fue fundada en París en 1878 bajo el nombre de Fédération Internationale des Géomètres y se conoce por su acrónimo francés FIG. Esta organización no gubernamental reúne a más de 100 países y fomenta la colaboración internacional en materia de agrimensura mediante la obtención de datos de las características de la tierra sobre, en y bajo la superficie y su representación gráfica en forma de mapas, planos o modelos digitales. La FIG lleva a cabo su labor a través de 10 comisiones que se especializan en los diferentes aspectos de la agrimensura. La Comisión 7, Catastro y Manejo de Suelos, se concentra en los asuntos relacionados con la reforma catastral y catastros de usos múltiples, sistemas de información sobre suelos basados en parcelas, levantamientos catastrales y cartografía, titulación y tenencia de suelos y legislación sobre los suelos y registro. Para obtener más información, visite la página Web www.fig.net/figtree/commission7/.

Catastros multifuncionales

En años recientes, la visión del catastro como un sistema de información multifuncional ha comenzado a evolucionar y a producir grandes avances en la calidad de los sistemas de información sobre suelos, pero también algunos problemas. El origen de estas inquietudes puede hallarse en el concepto mismo de los sistemas de catastros multifinalitarios y en las decisiones administrativas que se necesitan para su implementación. Existe una noción frecuente según la cual para implementar un catastro multifuncional es necesario ampliar las bases de datos alfanuméricas –incluidos los datos sociales, ambientales y también físicos (ubicación y forma), aspectos económicos y jurídicos de la parcela– y vincular esta información a un mapa de parcelas en un sistema de información geográfica (SIG). Aunque es un paso importante, no es suficiente.

La implementación de un catastro multifuncional implica un cambio de paradigma para su administración y exige una nueva estructura de usos del suelo y nuevas relaciones entre los sectores público y privado. En 1996 Brasil ideó un Congreso Nacional sobre Catastro Multifuncional que se celebraría cada dos años para evaluar sus propios programas estatales de catastro y los programas de otros países vecinos. Pese a la atención dedicada a los catastros y los muchos artículos que se han publicado desde entonces sobre el tema, no hay indicios de ninguna municipalidad en la cual el sistema catastral multifuncional opere de la manera que se esperaba.

Según las publicaciones existentes, para que un catastro sea realmente multifuncional es necesario integrar todas las instituciones públicas y privadas que trabajan al nivel de parcelas con un identificador único y definir parámetros para las bases de datos alfanuméricas y cartográficas. Chile es uno de los países donde todas las parcelas tienen un identificador común designado por la implementación del Sistema Nacional de Información Territorial, aunque el sistema todavía no ha integrado los datos catastrales alfanuméricos con los mapas a nivel de parcelas (Hyman et al. 2003).

Centralización y descentralización

La hegemonía del sistema unitario de gobierno que caracteriza a la mayoría de los países latinoamericanos ha propiciado el predominio de catastros centralizados, si bien este fenómeno también ocurre en países con gobierno federal. Brasil, por ejemplo, recientemente reestructuró su Sistema Nacional de Catastro Rural, el cual, a pesar de los avances tecnológicos propuestos en la Ley 10.267/2001, continuará bajo la administración de una institución del gobierno nacional.

En contraste, el movimiento de descentralización en la región aspira modernizar los gobiernos estatales mediante la transferencia de poderes a las jurisdicciones municipales, lo que abarca las instituciones encargadas de la administración del suelo. Por ejemplo, más de la mitad de los estados de México aún tienen datos catastrales centralizados, aunque algunos han comenzado la descentralización creando sistemas municipales compatibles con el catastro estatal. Una situación similar ocurre en Argentina, donde algunas instituciones provinciales están comenzando a transferir sistemas y datos a las municipalidades. Los administradores locales tienen un incentivo adicional por asumir la responsabilidad de organizar y mantener los sistemas catastrales debido a las oportunidades para recaudar impuestos sobre la propiedad y vender mapas o bases de datos registrados en el sistema catastral local a las compañías de servicios públicos y demás entidades del sector privado.

Sin embargo, todas estas buenas intenciones a menudo se tropiezan con el problema crónico de la escasez de personal capacitado e infraestructura. En algunos casos la descentralización puede constituir un problema más que una solución y podría poner en riesgo el mantenimiento y validación de la información. Por ejemplo, la adopción del modelo descentralizado puede conducir a la coexistencia de catastros sumamente detallados y precisos en algunos lugares y catastros casi inexistentes en otros. Tales discrepancias entre municipalidades vecinas pueden dar lugar a incongruencias cuando se incorpora la información sobre el suelo a nivel regional y nacional.

Por otra parte, un modelo centralizado puede facilitar la unificación del diseño y la estructura del catastro y garantizar la integración de sistemas geodésicos y cartográficos con la identificación de parcelas. Las dificultades de acceso y distribución de la información para satisfacer necesidades locales podrían resolverse usando Internet para organizar los datos y mapas a través de un catastro central. Algunos países, como Jamaica, Chile y Uruguay, comienzan a adoptar este enfoque para estructurar sus catastros en forma electrónica (llamados e-catastros, término derivado del concepto de eGovernment -administración electrónica- introducido por el Banco Mundial).

Al considerar las distintas etapas de desarrollo de los catastros en América Latina, podemos concluir que cada jurisdicción está obligada a analizar qué tipo de sistema resulta más adecuado para sus circunstancias particulares. Vale la pena considerar los Principios Comunes del Catastro en la Unión Europea, un documento que afirma que “no hay intención de unificar los sistemas catastrales de los Estados miembros; no obstante, si existe interés en estandarizar los productos” (Comité Permanente, 2003). Si es posible trabajar con sistemas catastrales diferentes en toda Europa, debe ser posible hacerlo en un mismo país.

Catastros públicos y catastros privados

Después de la publicación del Catastro 2014 de la Federación Internacional de Agrimensores (FIG), una de las nuevas visiones que suscitó mucho debate fue la propuesta de que el catastro debiera estar “altamente privatizado; el sector público y el sector privado trabajarán en conjunto, lo que reducirá el control y la supervisión por parte del sector público” (Kaufmann y Steudler 1998). Por ejemplo, en Japón las empresas privadas tienen el control prácticamente total de la base catastral de algunas ciudades, mientras que en los Estados miembros de la Unión Europea el catastro reside en la esfera gubernamental.

En América Latina los catastros se mantienen principalmente en manos de instituciones públicas; el sector privado por lo general participa en los procesos de implementación de actualizaciones cartográficas y sistemas de información, más no en la administración misma. La municipalidad mexicana de Guadalajara, por ejemplo, realizó un estudio comparativo de los costos y concluyó que el manejo del catastro con sus propios empleados y equipos significaría un ahorro del 50% en inversiones, lo que quedó confirmado un año después de la implementación.

Pese a los resultados positivos obtenidos en dichos proyectos desarrollados por completo dentro de la administración pública, no es posible dejar de lado al sector privado, especialmente en el contexto de la ola de privatización que ha sacudido a América Latina estos últimos años. Por ejemplo, al igual que las instituciones públicas, las compañías de teléfono, agua y energía eléctrica necesitan información territorial actualizada. El interés en común por mantener al día las bases de datos hace que las oficinas de catastro y las compañías de servicios públicos trabajen en colaboración y se repartan las inversiones, además de buscar maneras de estandarizar la información y definir identificadores comunes para las parcelas.

Conclusiones

La mayoría de los sistemas catastrales de América Latina siguen registrando tres tipos de datos según el modelo económico-físico-legal tradicional: el valor económico, la ubicación y forma de la parcela y la relación entre la propiedad y el propietario u ocupante. No obstante, existe un mayor interés en utilizar sistemas de información multifinalitarios. En este proceso de transición, algunos administradores han decidido implementar nuevas aplicaciones catastrales basadas en la tecnología, pero es evidente que no se ha logrado el éxito que ellos anticipaban. Esta incorporación de nuevas tecnologías debe estar acompañada de los cambios necesarios en los procedimientos y la legislación y de capacitación profesional de los empleados públicos.

En años recientes ciertas instituciones internacionales como el Banco Mundial, el Instituto Lincoln y muchas universidades europeas y estadounidenses han prestado su colaboración para ayudar a mejorar los catastros latinoamericanos. Ofrecen apoyo para programas educativos, actividades académicas y proyectos concretos con la finalidad de implementar sistemas de información territoriales que sean confiables y estén actualizados. A medida que continúa la transición hacia catastros multifinalitarios, se implementarán los cambios a través de una revisión minuciosa de la legislación pertinente, formas más accesibles de servicio a los usuarios, colaboración sólida entre las instituciones públicas y privadas que generen y utilicen datos catastrales, y la aplicación de estándares internacionales contemporáneos. Los catastros territoriales en América Latina llegarán a ser todavía más eficaces y útiles si generan información que propicie el desarrollo de proyectos orientados a las preocupaciones sociales fundamentales, como la regulación del suelo y la identificación de terrenos desocupados.

Diego Alfonso Erba es profesor de aplicaciones avanzadas de SIG y cartografía digital en la UNISINOS (Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos) en São Leopoldo-RS, Brasil, y docente invitado del Instituto Lincoln.

Referencias

Hyman, Glenn, Perea, Claudia, Rey, Dora Inés y Lance, Kate. 2003. Encuesta sobre el desarrollo de las infraestructuras nacionales de datos espaciales en América Latina y el Caribe. Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT).

Kaufmann, Jürg y Steudler, Daniel. 1998. Catastro 2014: Una visión para un sistema catastral futuro.

Frederiksberg, Dinamarca: Federación Internacional de Agrimensores (FIG). Documento disponible en la página http://www.swisstopo.ch/fig-wg71/cad2014/download/cat2014-espanol.pdf.

Comité Permanente sobre el Catastro en la Unión Europea. 2003. Principios Comunes del Catastro en la Unión en la Unión Europea. Roma. 3 de diciembre. Documento disponible en la página http://www.eurocadastre.org/pdf/Principles%20in%20Spanish.pdf.

State trust lands in the Intermountain West could play an important role in the growing market for renewable energy. Congress granted these territories, covering 35 million acres, to states upon their entry to the Union, to support schools and other public institutions. As managers of these state trust lands search for innovative and sustainable ways to lease and sell parcels to generate income, renewables could prove to be a double boon—by supplying clean, sustainable power and providing a strong revenue stream for the public benefit.

All seven states in the Intermountain West—Arizona, Idaho, Colorado, Montana, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming (figure 1)—are using state trust lands to develop renewables, including wind, solar, geothermal, and biomass projects. Yet the industry has not flourished to its full potential. In 2011, the installed renewable energy production capacity on state trust lands was only 360 megawatts—not enough to power 2 percent of the homes in the region. The $2 million in revenue generated by these sources on state trust lands amounts to less than 1 percent of the $1 billion-plus generated there annually by other means (Berry 2013; WSLCA). Wind energy is experiencing the most activity by far; all the Intermountain West states have leased state trust lands for wind projects, and all have operational wind farms. Although Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah have leased state trust lands for solar operations, only one generation facility is in production on state trust lands in the Intermountain West, in Arizona. Only Utah has a geothermal plant on state trust land, and no states in this region have active biomass facilities on trust lands.

This article will focus on three types of renewable energy production in three states—a wind farm in Montana, geothermal projects in Utah, and solar generation in Arizona—and the conditions, legislation, and other factors that led to successful operations. All three examples demonstrate that these territories offer a largely untapped bounty for this burgeoning, sustainable market; provide learning opportunities across state lines; and help meet growing demand for renewable energy.

Judith Gap Wind Farm, Montana

Judith Gap is Montana’s only operational wind farm on state trust land, straddling private land as well, in the central-eastern part of the state. It has 90 turbines total, each with a capacity of 1.5 megawatts; 13 are on state trust lands, on the leading edge of the wind farm, with a total capacity of 19.5 megawatts. The per-megawatt fee of approximately 2.6 percent of gross receipts brings in about $50,000 per year according to Mike Sullivan of the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation (DNRC). At the time of construction, there was a one-time installation fee of $20,000 (Rodman 2008).

Bob Quinn, founder of a local wind development company called Windpark Solutions, initiated the project in 2000, when he proposed the idea to a small group including representatives from the local utility, the Montana Department of Environmental Quality, and the DNRC. Quinn says that close collaboration between the developer and personnel in these state agencies was key to successfully siting the project on state trust land. State staff also helped Quinn navigate other difficult challenges including unanticipated delays in the request for proposals (RFP) process required by the state.

After conducting preliminary studies—allowed for one year through a land use license from the DNRC—developers must apply to the DNRC in order to proceed with energy projects. The state then issues a request for proposals (RFP). Applicants with a land use license do not receive preferential treatment. After a successful applicant is identified, the developer must conduct environmental analyses, secure a power purchase agreement with a utility, and determine economic feasibility before signing a lease with the DNRC. Currently, fees for new land use licenses are generally $2 per acre per year. Lease agreement costs for new wind projects include a one-time installation charge of $1,500 to $2,500 per megawatt of installed capacity, and annual fees of 3 percent of gross annual revenues or $3,000 for each megawatt of installed capacity, whichever is greater (Rodman 2008, Billings Gazette 2010).

Lease and Fee Structures

Every state has different leasing systems for renewable energy projects on state trust lands, but they all follow a similar pattern. The process usually starts with a short-term planning lease that allows for exploration and meteorological studies. The construction phase is next, followed by a longer-term production lease. Payments to the trust land management agency usually include a per-acre rent during the planning phase, which may continue into the production phase. There are additional installation charges for equipment, including meteorological towers, wind turbines, solar collectors, structures, and other infrastructure. During the production phase, the fee is typically based either on the installed capacity or the gross revenues of the generation facility.

Since Judith Gap was completed in 2005, several wind farms have proposed development on state trust lands in Montana, but none have reached the production phase. These include the Springdale Wind Energy project—an 80-megawatt wind farm consisting of 44 turbines, 8 of which would be on state trust lands. The DNRC has also leased 3,000 acres near Martinsdale to Horizon Wind Energy for a wind farm with 27 turbines, 7 to 15 of which would be on state trust lands. The Martinsdale wind farm could expand to 100 turbines in the future (MT DNRC).

In order to make state trust lands more attractive to these and other renewable energy developers, the DNRC would benefit from a more streamlined process. Developers working on state trust lands in Montana have cited struggles with timing, financing, environmental mitigation, cooperation from power buyers, and transmission (Rodman 2008). According to Quinn, Judith Gap succeeded in part due to dedication and close collaboration between agency personnel and the energy developer. In the future, the DNRC may need to assign personnel to renewable energy projects in order to guide developers through the process. The DNRC could also attract projects by granting land use license holders preferential status in the RFP process and by opening up bidding faster. Quinn notes that evaluating bids according to performance rather than price alone would improve the system.

Geothermal Energy, Utah

Geothermal energy is a potentially constant power source, offsetting fluctuations from intermittent renewables such as wind and solar. However, it’s also technically complex and expensive—and thus rare on state trust lands in the Intermountain West. Utah is currently the only state in the region with active geothermal facilities on state trust land. Measured by land area, geothermal is Utah’s largest renewable energy supply, with approximately 100,000 acres leased on state trust lands. There are currently two geothermal energy plants in production, generating revenue of $200,000 to $300,000 per year. For geothermal projects, the State and Institutional Trust Lands Administration (SITLA), which manages state trust lands in Utah, charges 2.25 percent of electricity sales for the first 5 or 10 years, and 3.5 percent thereafter.

PacifiCorp’s 34-megawatt Blundell plant, on a mix of federal, state, and private territory, was the state’s first, built in 1984. Blundell taps into an underground reservoir that is 3,000 feet deep, more than 500° F, and pressurized at 500 pounds per square inch. A well brings the hot, high-pressure water to the surface, where it powers a steam turbine. The Blundell plant has two units, a 23-megawatt unit built in 1984 and an 11-megawatt unit completed in 2007.

The newer Raser plant in Beaver County has been less successful. Raser originally planned to build a 15-megawatt operation using a new, modular technology produced by United Technologies, says John Andrews, SITLA associate director. The company aimed to cut costs and development time by exploring the geothermal resource while constructing the generation facility—instead of fully developing geothermal wells first, then building the power plant later. Unfortunately, the geothermal resource fell short of expectations and could not support a 15-megawatt operation. With limited income, Raser could not cover debts and declared bankruptcy in 2011. The plant continues to run at limited capacity (Oberbeck 2009).

The experience at Raser shows that the costs of geothermal development continue to be daunting and that it’s worthwhile to fully characterize the available geothermal resource prior to constructing generation facilities, although that additional step is costly and time-consuming. Future technological advances may help to cut the costs and time required for geothermal development, but, given the current state of technology, geothermal projects still require significant upfront outlays.

For renewable energy development, SITLA responds to applications as they are received; they can also offer lands through a request for proposals or a competitive sealed bid process (Rodman 2008). The state has mapped renewable energy zones, but the task of finding locations and proposing renewable energy projects devolves to developers.

Utah faces other challenges to all forms of renewable energy development on trust lands. Because of the high proportion and pattern of federally owned territory, national agencies sometimes take the lead on energy development projects. According to Andrews, the absence of an RPS in Utah is another drawback, leaving local utilities without a state mandate to supply renewable energy.

Even without an RPS, however, Utah is geographically well-positioned to export energy to other states—particularly to population centers on the west coast. Although transmission can be a barrier in some parts of the state, transmission capacity is available between Utah and southern California. What’s more, developers can tap an array of renewable resources—wind, solar, and geothermal. SITLA would benefit from marketing trust lands within renewable energy zones to potential developers and by offering reduced rates for renewable energy projects within these areas.

Solar Developments in Arizona

Even in Arizona—the sunniest state in the U.S., according to the National Weather Service—the solar industry faces several obstacles on state trust lands. The only active solar facility on state trust lands, the Foothills Solar Plant opened on 400 acres in Yuma County in April 2013, when the first 17 megawatts came online. An additional 18 megawatts are scheduled to go online in December 2013. Once it’s fully operational, the facility will serve 9,000 customers. The 35-year lease will generate $10 million for state trust lands beneficiaries, and most of that money will fund public education.

The slow development of the solar industry on trust lands mirrors a larger trend seen nationwide. In 2010, only 0.03 percent of the nation’s energy came from solar projects, while 2.3 percent came from wind (www.eia.gov). Solar projects usually require exclusive use of a site—putting them at an even greater disadvantage on state trust lands, where many acres are already leased for agriculture, grazing, or oil and gas production. Wind projects, by contrast, can co-exist with other land uses. Solar projects also require large tracts—as many as 12 acres per megawatt (Culp and Gibbons 2010)—whereas wind facilities have a relatively small footprint. And, although prices are dropping, solar generation facilities can be very expensive.

Despite these drawbacks, there are ways in which solar development is well-suited to state trust lands. For starters, these territories are untaxed and owned free and clear; unburdened by the carrying costs that private owners might have, state trust land management agencies have an advantage for holding and maintaining renewable energy projects. Some solar developers have found state trust land attractive because they can work with one owner for very large tracts. Solar generation is also well-suited to previously disturbed sites, such as old landfills and abandoned agricultural areas, which may include trust lands. Near urban areas, state trust lands slated for future development could be used for solar generation in the interim; after the solar leases expire, the grounds could be developed for urban uses (Culp and Gibbons 2010).

State-level RPS and tax incentives could also encourage solar development. Some states provide up to 25 percent investment tax credits, property tax exemptions, and standard-offer contracts on solar, guaranteeing a long-term market for solar output.

As one of the largest landowners in the state, with several large, consolidated parcels, the Arizona State Land Department (ASLD) would do well to position itself as an attractive partner for the renewable energy industry (Wadsack 2009). The ASLD is taking steps in the right direction by developing a GIS-based renewable energy mapping system to analyze state trust lands for general suitability for solar production, based on avoiding critical wildlife habitat and wilderness areas, and minimizing distance to roads, transmission, and load. But it must follow up and market the most suitable areas for renewables (Culp and Gibbons 2010) and facilitate the process for developers, who can be deterred by complex leasing structures, requirements for public auctions, and required environmental and cultural analyses (Wadsack 2009). The more the agency can build capacity to help developers through this process, the more the renewable energy industry might flourish on state trust lands. For example, the department could offer long-term leases, expedite land sales, or develop a reduced-cost, revenue-sharing lease system specifically tailored for renewable energy development.

General Recommendations for Montana, Utah, and Arizona

Leasing renewable energy on state trust lands is complicated. Each state has a unique set of political, environmental, and economic circumstances that makes it difficult to determine any one best method for all. However, the accomplishments, problems, and solutions detailed in the examples above provide some general recommendations for success.

At the state land trust agency level:

At the state level:

Federal policies play a considerable role as well. Production tax credits in particular have spurred U.S. renewable energy deployment in recent decades. Likewise, federal investment tax credits for renewable energy—which provide developers with a tax credit during the planning and construction phases—have helped the renewable energy industry grow in recent years, even when the national economy was in recession. Finally, there have been several proposals for a federal-level renewable portfolio standard, although researchers disagree whether this type of policy would interfere with existing state-level RPS policies, which have proven extremely effective.

Renewable energy offers state trust land managers an opportunity to diversify their revenue stream to benefit the public good. For the most part, wind and transmission projects can be co-located with pre-existing leases for grazing, agriculture, oil, and gas. Solar projects could have great potential in previously disturbed sites or areas with little other value. Where geothermal resources are available, they offer consistent power that can offset intermittent sources like wind or solar. Technological advances could help bring down prices for renewables, particularly solar, geothermal, and biomass. As our energy demands grow, state trust lands are poised to play an important role in the growing renewable energy industry.

This article was adapted from the Lincoln Institute working paper, “Leasing Renewable Energy on State Trust Lands,” available online here: http://www.lincolninst.edu/pubs/dl/2192_1518_Berry_WP12AB1.pdf.

About the Author

Alison Berry is the energy and economics specialist at the Sonoran Institute, where her work focuses on land use issues in a changing West. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Vermont and a master’s degree in forestry from the University of Montana. Her work has been published in the Wall Street Journal, the Journal of Forestry, and the Western Journal of Applied Forestry, among other publications. Contact: aberry@sonoraninstitute.org.

Resources

Berry, Jason, David Hurlbut, Richard Simon, Joseph Moore, and Robert Blackett. 2009. Utah Renewable Energy Zones Task Force Phase I Report. http://www.energy.utah.gov/renewable_energy/docs/mp-09-1low.pdf.

Billings Gazette. 2010. Wind farm developers eye school trust land. April 22. http://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/montana/article_14bfb038-4e0a-11df-bc99-001cc4c002e0.html.

Bureau of Land Management. 2011. Restoration Design Energy Project. http://www.blm.gov/az/st/en/prog/energy/arra_solar.html.

Culp, Peter, and Jocelyn Gibbons. 2010. Strategies for Renewable Energy Projects on Arizona’s State Trust Lands. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper WP11PC2. https://www.lincolninst.edu/pubs/dl/1984_1306_CulpGibbon%20Final.pdf.

Montana Department of Natural Resources. 2011. Montana’s Trust Lands. Presented at the Western States Land Commissioners Association annual meeting. Online: http://www.glo.texas.gov/wslca/pdf/state-reports-2011/wslca-presentation-mt-2011.pdf accessed November 23, 2011.

Oberbeck, Steven. 2009. Utah geothermal plant runs into cold-water problems. Salt Lake Tribune. September 17. And Bathon, Michael. 2011. Utah’s Raser Technologies files Chapter 11. Salt Lake Tribune. May 2.

Rodman, Nancy Welch. 2008. Wind, wave/tidal, and in-river flow energy: A review of the decision framework of state land management agencies. Prepared for the Western States Land Commissioners Association. http://www.glo.texas.gov/wslca/pdf/wind_wave_tidal_river.pdf.

Wadsack, Karin. 2009 Arizona Wind Development Status Report. Arizona Corporation Commission.

The case of Mexicali, the capital city of the border state of Baja California, Mexico, stands out as a good example of successful property tax reform in the 1990s. In only a few years the local government was able to raise revenues associated with the property tax, as well as strengthen its municipal finances and modernize its cadastral and collection systems. Furthermore, Mexicali carried out this reform by adopting a land value taxation system, the first of its kind in Mexico, and gained the public’s acceptance for these changes. Without ignoring its problems and flaws, this case provides interesting lessons on future property tax reform endeavors in Mexico and other countries.

Economic, Political and Technical Considerations

Accomplishing property tax reform did not always seem to be an easy task in Mexicali or anywhere in Mexico. Since 1983, the local level of government has been responsible for setting up and collecting property taxes, although state authorities kept certain responsibilities. Throughout the 1980s, property tax revenues, and local revenues in general, experienced a severe drop caused by a combination of high inflation rates, economic recession, lack of political interest, and reduced administrative competence of local governments, which preferred to rely on revenue-sharing sources.

In the early 1990s, a clear improvement in the nation’s macro-economic performance made conditions more favorable for change, although political and technical factors reduced the incentives for many state and local governments to embark on fiscal reform. Nevertheless, the federal administration of Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1989-1994) launched an initiative to improve local finances through a cadastre modernization program lead by BANOBRAS (Banco Nacional de Obras y Servicios), a public development bank.

Even before this program and other national policies began to exert an influence on local and state administrations, Mexicali took the lead in property tax reform. Starting in 1989, the newly elected mayor, Milton Castellanos Gout, saw the importance of having strong local finances and wanted to raise revenues at the beginning of his term. He hired a private consulting firm to update cadastral values. The main consultant, Sergio Flores Peña, a graduate in city and regional planning from the University of California at Berkeley, convinced the mayor to change from a mixed-value tax base on land and buildings to a land value system, and to design a mathematical model to calculate land values.

Rather than being attracted by theoretical or ideological beliefs about the advantages of a land value tax, Castellanos was convinced that it would be the easiest and fastest way to raise revenues. He took the political risk of proposing a Municipal Cadastral Committee, including real estate owners’ organizations, professional organizations and citizen representatives.

The results were spectacular in two ways: first, the new tax raised revenues quickly (see Table 1); and second, there was not a single legal or political objection from taxpayers. The increase in revenues from real estate property taxes and property sales, by far the most important source of local revenues, allowed the mayor to launch an important public works program. In the next fiscal year, however, he wanted to loosen his fiscal grip, so he did not pursue land valuation updates and abandoned the mathematical model that was originally created for that purpose.

Opposition to updating land values came from both the Municipal Cadastral Committee and the government officials in charge of the cadastre and valuation office who lacked the technical capability to manipulate the model and feared that their power and control might be weakened by the participation of the private consulting firm. As a result, the mathematical model was abandoned and land values where subsequently defined by a process of negotiation and bargaining between local authorities, elected representatives and the committee. However, the land value taxation system remained as the base to establish land values.

At the same time, the Castellanos administration embarked on a cadastre modernization program with financial resources from the federal government. However, since the mayor saw that his main objective of raising revenues had been achieved, the efforts to modernize the cadastral system became a secondary priority that was not as successful.

In subsequent administrations, the policy towards tax revenues and cadastre modernization varied. The next mayor, Francisco Pérez Tejeda (1992-1995), was a member of the same political party (Partido Revolucionario Institucional, PRI). He experienced a drop in property tax revenue during his first year in office, and taxes only increased at the end of his administration. He abandoned the cadastre modernization program, but maintained the land value taxation system.

The next administration was led by Eugenio Elourdy (1995-1998), a member of the Partido de Acción Nacional (PAN). He was the first opposition party leader in Mexicali, although a member of PAN had governed at the state level from 1989 to 1994. During Elourdy’s term, land values were updated, property tax revenues grew steadily and cadastre modernization was vigorously resumed. The current administration led by Victor Hermosillo (1999-2001) is continuing with cadastre reform.

Assessing the Mexicali Experience

There is no question that the process of fiscal reform has stimulated property tax revenues as the fastest and most important financial source for the city government. Currently, property tax revenues account for more than 50 percent of local municipal revenues. Mexicali is well above the state and national averages for the relative share of property tax revenues to total revenues (15.3 percent in 1995, compared to 8.4 percent at the state level and 10.3 percent at the national level). Local government officials in charge of the cadastre and valuation systems are well prepared with technical expertise and an awareness of the need to conduct permanent reform within the system. Mexicali’s example has already been replicated in the rest of the state of Baja California and in the neighboring state of Baja California Sur.

The Mexicali case offers some important lessons. First, the property tax plays a central role in strengthening local governments, not only for raising sufficient revenues for urban development but also for providing government officials with the skills to organize the tax system in a way that can be sound, legitimate and transparent.

Second, property tax reform requires vision, leadership and, most of all, political will and commitment from the executive. However, successful reform to raise taxes also depends on a sound technical base and acceptance by the general public.

Third, the land value tax proved to be extremely helpful in achieving successful reform at an early stage. It is clear that the rationale for adopting land value taxation had more to do with a pragmatic approach than with theoretical positions or debates over different schools of thought. However, this should not prevent government officials, consultants, scholars and the general public from thoroughly analyzing the diverse consequences of this approach in terms of economic efficiency, equity and administrative management.

Although a land value tax has proven to be successful in the case of Mexicali, it should not be viewed as a panacea for all situations. It is important to recognize that the tax can be of little help without other measures that have to be considered as part of property tax reform, such as cadastre modernization, clear policies on tax rates and public participation.

Finally, cases of property tax reform around the world cannot be viewed as black-and-white, success-or-failure experiences, but rather, like Mexicali, as stories that combine success, flaws and steps backward. Far from being a perfect example of property tax reform, Mexicali is a good learning experience. It shows that changes can take place in a field where very often one thinks that little can be accomplished.

Manuel Perlo Cohen is a researcher at the Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. He received support for this case study from the Lincoln Institute and he has participated in numerous Institute-sponsored courses and seminars throughout Latin America.

Latin America is a region of sharp contrasts in land use: the expansive Amazon forest and growing areas of deforestation; large uninhabited regions and enormous urban concentrations; the coexistence of wealth and poverty in the same neighborhoods. Many of these contrasts derive from land policies established by powerful land interests that are perpetuated because of outdated or distorted data. This heritage is a part of the region’s colonization process that has been characterized by the exploitation and occupation of land at any price.

The first land information system for registering parcels in Latin America was established in 1824 by the Topographic Commission in the Province of Buenos Aires in the Republic of Argentina. Territorial cadastre offices throughout the region now manage public land information systems that register maps and data about the parcels on which taxes are levied and rights are granted to the owners or occupants of the land.

What Is a Cadastre?

A modern cadastre is an integrated database system that holds information on land registration and ownership, physical characteristics, econometric modeling for property valuation, zoning, geographic information systems, transportation, and environmental, socioeconomic and demographic data. Such cadastres represent a holistic planning tool that can be used at the local, regional and national levels to address issues such as economic development, sprawl, poverty eradication, land policy and sustainable community development.

The earliest recorded accounts of property surveys in ancient Egypt used the science of geometry to measure distances. European cadastres later followed this ancient model until advancements led to more fully integrated systems that could be used for fiscal purposes, such as valuation, taxation and legal conveyance, as well as land management and planning. The United States does not have a national cadastral system, but similar municipal processes reflect both the policy and protocol of international cadastre programs.

The International Federation of Surveyors was founded in Paris in 1878 as the Fédération Internationale des Géomètres and is known by its acronym, FIG. This nongovernmental organization represents more than 100 countries and supports international collaboration on surveying through the collection of data on surface and near-surface features of the earth and their representation as a map, plan or digital model. FIG’s work is conducted by 10 commissions that specialize in different aspects of surveying. Commission 7, Cadastre and Land Management, focuses on issues in cadastral reform and multipurpose cadastres; parcel-based land information systems; cadastral surveying and mapping; and land titling, land tenure, land law and registration. For more information, see www.fig.net/figtree/commission7/.

Multipurpose Cadastres

In recent years, the vision of the cadastre as a multipurpose information system has begun to evolve, bringing with it great advances in the quality of land information systems, as well as some problems. The origin of these concerns can be found in the very concept of multipurpose cadastre systems and in the administrative decisions needed for their implementation. A common assumption holds that to implement a multipurpose cadastre it is necessary to expand the alphanumeric databases—including social and environmental data as well as the usual physical (location and shape), economic and legal aspects of the parcel—and to connect this information with a parcel map in a geographical information system (GIS). While this is very important, it is not enough.

Implementation of a multipurpose cadastre implies a change of paradigm for its administration and demands a new land use framework law and new relationships between the public and private sectors. In 1996 Brazil established a biannual National Multipurpose Cadastral Congress that examines its own state-level cadastre programs and those in neighboring countries. Despite the attention devoted to cadastres and the many papers published on the topic since then, there is no evidence of any municipality in which the multipurpose cadastral system is actually working as well as hoped.

According to the literature, the way to make a cadastre truly multipurpose is to integrate all the public and private institutions that are working at the parcel level using a unique identifier, and to define standards for the alphanumeric and cartographic databases. Chile is one of the countries where all the parcels have a common identifier designated by the implementation of the National Territorial Information System, although the system does not yet integrate the alphanumeric cadastral data with maps at the parcel level (Hyman et al. 2003).

Centralization versus Decentralization

The hegemony of the unitary system of government that characterizes most Latin American countries has caused a predominance of centralized cadastres, although this phenomenon also occurs in countries with a federal government. Brazil, for example, recently restructured its National System of Rural Cadastre, which, in spite of the technical advances proposed by Law 10.267/2001, will continue to be administered by an institution of the national government.

In contrast, the decentralization movement in the region aspires to modernize state governments by transferring powers to municipal jurisdictions, including the institutions responsible for land administration. For example, more than half of the states in Mexico still have centralized cadastral data, although some have begun to decentralize by creating municipal systems that are compatible with the state cadastre. A similar situation is occurring in Argentina, where some provincial institutions are beginning to transfer systems and data to the municipalities. Local administrators have an added incentive for assuming responsibility for organizing and maintaining cadastral systems because of the opportunities to collect property taxes and sell maps or databases registered in the local cadastral system to utility companies and other entities in the private sector.