The Colorado River Basin includes four of the eight fastest-growing states in the nation: Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, and Utah. All seven of the basin states project strong population growth over the next decade, placing pressure on a river system that is already overallocated. Water conservation, water sharing agreements, and the integration of water into land use planning will be key strategies for ensuring long-term, sustainable resource use.

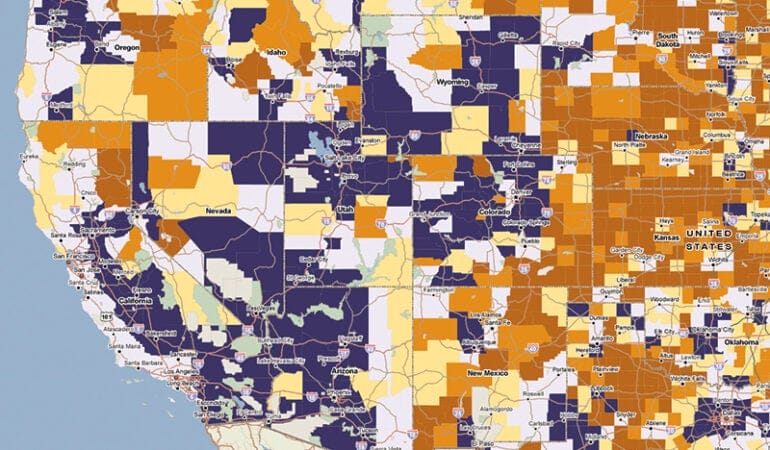

View the PDF version of this map for more detail and a key.

Source: The Place Database. www.lincolninst.edu/research-data/data/place-database

Four years ago, I found myself in an airplane above the Colorado Delta with Katie Lincoln, our board chair. From our shared vantage point, we could see miles and miles of dry and dusty river sediment and scarce vegetation. It was a stunning, vast, otherworldly landscape, painted with a thousand shades of beige.

On the ground, we saw a different story. Eleven months earlier, the United States and Mexico had released a “pulse flow” from dams on the Colorado River to mimic the historic spring floods that occurred for millennia before humans began managing the river’s waters. More than 100,000 acre-feet of water—enough to meet the annual needs of more than 200,000 households—flowed south to satisfy provisions and promises that had been made between the two countries years before; for the first time in two decades, the river reached the Gulf of California.

Leading up to that event, public and civic actors from the two countries prepared an experiment to see whether the natural habitat of the delta could be restored with improved water flow. They cleared about 320 acres of land near Laguna Grande of non-native vegetation, seeded some of the land with native plants, and planted native trees in other sections. By the time Katie and I visited the site, the success of the experiment was obvious. Native flora was thriving, and it was attracting native fauna back to the site. Both migratory and non-migratory birds made their presence known with a cacophony of calls and responses. As luck would have it, two beavers had taken up residence next to the restoration site. Their dam captured return flow from groundwater and agricultural irrigation to provide a more reliable water supply.

This land use experiment, which had been invisible from the air, demonstrated clearly that native habitat could be restored in the delta. It also was clear that much more needed to be done.

At one time, the delta was the largest wetland in North America, covering some 173 million acres. After the headline-making pulse flow in 2014—which was actually a return of water due to Mexico that had been stored in Lake Mead, following a 2010 earthquake that damaged irrigation canals south of Mexicali—the United States and Mexico negotiated the release of more regular, more gradual base flows. In September 2017, they agreed on the delivery of 210,000 acre-feet of water to the delta over the next decade. Earlier this year, the Natural Resources Defense Council reported that the original restoration site at Laguna Grande had grown to more than 1,200 acres.

In many ways, the success of that little patch of land is the story of the entire Colorado River Basin. When you look at the big picture—when you peer down from an actual or figurative mile-high perspective—you see a complex system, a tangle of geography and history and culture, a limited, nearly tapped out resource that multiple states, tribes, and countries have relied on, shared, and fought over for the last century. But get down to the ground and poke around a little, and you see something else: Little patches where innovation and collaboration are blooming. Restorative partnerships and renewed commitments to confronting seemingly intractable issues. A growing understanding of the importance of recognizing the intersections of water, land, and people.

During our debrief following the tour, I asked our hosts about the end game for the delta—what would it take to restore the entire place? The pulse flow was a singular moment, produced by a constellation of events and aided by diplomatic intervention. It would take a different alignment of actors to generate a permanent solution. But which actors? Would it be possible to promote civil discourse among the river’s stakeholders to conceive a collective solution to manage this precious resource? Who would convene them?

This is a hotly contested watershed. The river supplies drinking water to more than 40 million people, more than half of whom live outside the basin; irrigates more than 5.5 million acres of farmland; and produces more than 4 gigawatts of electrical power. Because the river is allocated—actually, overallocated—through a byzantine web of water rights, interstate agreements, and an international treaty, forging new agreements and practices among these stakeholders might seem to be an insurmountable task.

Just because something is hard doesn’t mean it’s not worth doing. We decided to find out whether and how the Lincoln Institute could contribute to better stewardship of the river.

We embarked on field research to find out who was already working on water issues in the basin and assessed our own core competencies. We wanted to see whether there was demand for our potential contributions. Could we leverage our knowledge and experience in the areas of land policy and stakeholder engagement? Should we extend our efforts at collecting, curating, and mapping new data sets? Should we adapt and advance the use of our scenario-planning tools to promote informed decision making and better civic engagement?

We encountered a crowded field of researchers, advocates, technicians, and dedicated public servants. Universities and government agencies continuously study the science of the river. Policy makers and analysts cover the broad contours of basinwide policy. Various experts are producing and perfecting technical projections of demographic, drought, and development scenarios. We noted, however, that the nexus of land and water policy was a neglected but critical niche in the field. Land use decisions are often made without consideration of their impacts on water, putting the sustainability of our communities and the river at risk. We founded the Babbitt Center for Land and Water Policy to explore and nurture the critical economic and environmental connections between land and water.

We dedicated the center to Bruce Babbitt, former U.S. Secretary of Interior, governor of Arizona, and member of the Lincoln Institute’s board of directors. Babbitt first first codified the connection between land use planning and water management in state law when he signed the Arizona Groundwater Act of 1980.

The Babbitt Center primarily focuses on the Colorado River and those who depend on it, but we don’t work alone. We know that effective long-term stewardship of this immense but fragile resource is a huge endeavor requiring broad collaboration. With intellectual and financial support from the Lincoln Institute, the center is leveraging the resources of others, establishing partnerships with universities, NGOs, and funders.

We are lucky to have an incredibly knowledgeable and committed staff at the Babbitt Center headquarters in Phoenix, many of whom worked on this issue of Land Lines. Director Jim Holway is no stranger to western water policy negotiations, as the former assistant director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources and current vice president of the Central Arizona Water Conservation District board of directors. He had this to say when I asked him, after he took a recent Grand Canyon rafting trip, to reflect on what’s at stake in the basin:

Looking forward, Colorado River managers will face numerous political rapids and significant uncertainty about future climate, water supply, and water demand conditions. However, we face nothing like the dangers and hardships faced by the early explorers of the Colorado. Solutions to our challenges do exist, and we can build on John Wesley Powell’s legacy of exploring the Colorado Basin, of understanding how to sustainably manage the lands and limited water resources of this arid region, and of challenging conventional thinking.

Challenging conventional thinking. Although we launched our work in the Colorado River Basin, we know that it will have global relevance. Through the broader reach of the Lincoln Institute, we are already initiating partnerships with global partners like the OECD and the UN. According to the UN, more than 1.7 billion people around the world live in river basins where water use exceeds recharge.

This special issue of Land Lines—the first issue of the publication’s 30th year—captures our early efforts to build a body of knowledge that articulates the important relationship between land and water. In these pages, we identify the challenges in the Colorado Basin, take a brief tour through its history, and talk with some of the smartest people we know to find out what the future holds. We also look at some innovative efforts being undertaken to better integrate land and water policies in pioneering communities. As we share this knowledge with other communities in arid and semi-arid regions throughout the world, we will do our small part to satisfy the primordial human fascination with places where land and water meet.

Bruce Babbitt has been a leader on western land and water policy for nearly half a century. He served as Arizona attorney general from 1975 to 1978, Arizona governor from 1978 to 1987, and U.S. Secretary of the Interior from 1993 to 2001. Secretary Babbitt, the namesake of the Babbitt Center for Land and Water Policy, also served on the board of directors for the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy from 2009 to 2017. Among his numerous accomplishments was the adoption of Arizona’s Groundwater Management Act during his tenure as governor. For the past two years, he served as an advisor to California Governor Jerry Brown on state water issues. He spoke with Dr. Jim Holway, director of the Babbitt Center, for this special issue of Land Lines.

Jim Holway: Bruce, from your perspective, what is the importance of the Colorado River?

Bruce Babbitt: Well, John Wesley Powell answered that question nearly 150 years ago. We live in a land of sparse rainfall, and not enough water flowing down to our rivers. Demand will always be running ahead of supply. And how we come to grips with that as a political culture is kind of the big reality of the Colorado River. Historically, water use was largely agricultural, but urban demand is constantly increasing due to population growth. Western growth and progress is going to require a lot of imagination and innovation in our use of this river.

JH: What is the role of the river in the economy and quality of life in the Southwest?

BB: Without the Colorado River, this would be a mighty empty land. That’s the reality. We have populated and settled this land on a “build it, and the water will come” basis. And you know, it’s a spectacular part of our history. It is kind of embedded in our view of the West as a land of infinite opportunity. But we are now discovering the limits. Agricultural and urban needs are coming into conflict. We also need to factor in environmental and ecological values that have been long neglected—and that add so much to the quality of life and the appeal of the American West.

JH: What is the state of the river today, and how has it changed since your tenure as Secretary of the Interior?

BB: When I went to Washington in 1993 to become Secretary of the Interior, Lake Powell and Lake Mead were full to overflowing, and the Colorado River didn’t seem to be of much immediate concern. Our perception was driven by the fact that this was a system overflowing with possibility. Today, scarcely 25 year later, Lake Mead is approaching dead pool, at which point it can no longer release water or generate power. This transition, which we did not anticipate or plan for, is a stark reminder of the need for long-range scenario planning for use of land and water.

JH: What do you view as the major Colorado River challenges we need to address?

BB: The first challenge is to recognize that we live in a desert with huge and rapid climatic fluctuations. Across the twentieth century, we built the great system of reservoirs to store water against these fluctuations. But our assumptions regarding climate change and population growth were way off. We are now drawing more than a million acre-feet out of reservoir storage each year in excess of average inflow. And obviously that cannot continue. We must now work toward establishing balance across the entire basin. To get to that equilibrium will require adjustments from every water user: agricultural, municipal, power generation, and environmental uses. And it obviously can’t be done on a piecemeal, ad hoc basis; we’ll have to invent new processes of public involvement and shared adjustments from every town and city and farm in the basin.

JH: What policy and management structures do we need to move toward a more balanced approach?

BB: In the West, connecting and integrating land and water use is a relatively new idea. Water use, like land use and zoning, has traditionally been a local affair, with little coordination or direction at the state or interstate level. But water is a common resource; developing on a local, project by project basis without thinking about regional supply and demand constraints inevitably leads to the crises and environmental degradation that we are now experiencing. The question is how to change that.

JH: What do you see as the most difficult policy or political challenges?

BB: Moving toward more proactive planning will be a social and political challenge. It can’t be accomplished by issuing regulations from on high in Washington or Phoenix or Denver. We need to begin at the personal level and move up from the ground. Begin with a renewed personal conservation ethic, engage communities in efficiency and reuse programs, integrate water into local land use and zoning, and propagate local success stories into state policies and then into basin-wide policy.

JH: Are the states the key to this bigger, system-wide view, or is it a federal role?

BB: You know, one of the remarkable things about the Colorado River is that it’s the only river basin in the United States that is managed and operated under the direction of the federal government. In 1963, after nearly a century of warfare among the basin states, the Supreme Court stepped in, dictated a formula for sharing the water, and then appointed the Secretary of the Interior to manage the river and its reservoirs. At the time, many westerners felt that such a takeover would be a disaster. In fact, it has worked very well, mainly because successive secretaries have used their power judiciously, encouraging the states to cooperate among themselves, and stepping in only as a last resort when the states could not agree. That has provided both impetus and threat, setting the table for the states to come together.

JH: When you were Secretary of the Interior, you utilized this “speak softly, but carry a big stick” approach. Are you optimistic about the role the states are playing or do you feel they need more encouragement to step up?

BB: Although this federal-state management system has worked well to date, it needs improvement. An example is the current negotiation among the Interior Department and the states over the shortages occurring in Lake Mead. Those discussions have moved in fits and starts, with shortage projections constantly under revision. Remarkably, there is not even a standing interstate organization in existence to guide data gathering, research, and planning efforts. We’re going to have to find some way to be more proactive, not to wait until the eleventh hour. We’re going to have to move it up to the sixth or seventh hour and anticipate the possible scenarios we’re looking at in the next decade, the next two or three decades.

JH: Along the lines of rethinking old patterns, what are the most effective ways to bring local land and water planning and management together?

BB: We need to devise new means of planning within each of the basin states. We can learn a lot from traditional land use planning and zoning, which can now be connected with and integrated into planning for water use. Call it land-water use planning. We can begin with local examples of conservation and water use efficiency, which should then extend to broader planning efforts such as the “assured water supply” legislation in Arizona—a very basic but innovative law that simply said, before you put a spade in the ground, you’ve got to show us what’s going to run through the faucets for the next 100 years . . . Climbing up the staircase of water management and across the staircases of municipal, county, state, multi-state, and federal government, it is important to go out and look at good examples like that.

JH: As Governor of Arizona, you led efforts to adopt the 1980 Groundwater Management Act. Do you feel the conversation about rural water issues has changed since then?

BB: It has not changed. Arizona is an instructive example of the need to set up planning processes and then keep up the effort, year after year, to improve and expand their application. The Groundwater Management Act of 1980 revolutionized water management in the urban counties that include Phoenix and Tucson. However, in the 35 odd years since then, the Act has not been extended to the rural areas of the state, which are now encountering the same issues of rapid development and demand. Political leadership matters, and it has been in short supply in Arizona and across the West.

JH: You have served as both the Governor of Arizona and the U.S. Secretary of the Interior. With the advantage of hindsight, are there key things you would have done differently?

BB: Well, look, where you stand often depends on where you sit. It would not be unfair to look across my time in public office and say, didn’t he used to be kind of a state’s rights guy, giving all those speeches about that evil bureaucracy in Washington, and then you pick up my speeches 20 years later, and I tended to frame it the other way. The fact is, it’s not one or the other; we must work together at all levels of government, from the very local up to the state capitols and on to Washington.

Looking back, I know I sometimes underestimated the importance of advocacy and direct voter engagement. In the past, there were times when I was impatient, when I wished I could take action instead of taking time to listen at town halls. I think if I could go back, I would spend more time on federal-state partnerships—and I’d also spend a lot more time thinking about those town halls.

JH: Where does the leadership need to come from to address the challenges you’ve identified?

BB: Americans have always been skeptical of government, and that’s really what the Constitution is about—appropriate limits on government. In the sweep of American history, we have tended to be pragmatic, optimistic, and open-minded about what needs to be done. We are perfectly capable of saying we don’t want the federal government, then in the same breath demanding federal help.

At present we are witness to a near collapse of the traditional federal-state partnership as the federal government declines into an idiosyncratic and unpredictable presence in the West. It’s really unfortunate. We’ve been through these periods in American history before. And we’ll get through this one.

This collapse at the national level is being counterbalanced by a renewal of interest and participation in local government. American history is instructing us once again that when the national government goes stale, there often comes a grassroots renewal across the land. And that is a great opportunity for all of us to reinvigorate planning from the grassroots upward.

JH: What led you to give your name to the Babbitt Center for Land and Water Policy?

BB: I was educated as a geologist and tend to approach problems in linear, formulaic terms. During my time as a Lincoln Institute board member, I came to a much deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of land and water use with economics, and the social and political aspects of land use. Lincoln has a long and impressive history of bringing together deep, data-driven research, multiple academic disciplines, and real-world practitioners to bring new insights to how we live and prosper on the land. If my presence and experience can add even a small amount to the Lincoln mission, I am eager to continue learning and contributing.

JH: Given your extensive international experience, what lessons from elsewhere do you think the Babbitt Center and others could bring back to the Colorado River Basin?

BB: Early on, David Lincoln and his family decided to extend the work of the Lincoln Institute to two places that have always been of special interest to me: China and Latin America. Both regions face complex water issues, heightened by the onset of global warming, from which we can learn and to which we can contribute from our own experience. Climate change is accelerating most at the poles and in the tropics and the near-tropics. So we kind of have an advanced projection, in a different context, of the kinds of things that we’re going to need to be dealing with in the Colorado River Basin.

JH: What are you doing now? What’s next for you?

BB: Well, at some point I’ll probably head back to Brazil and the Amazon Basin, where I have long been involved in conservation causes. But out here in the West, those of us who are obsessed with water are known as “water buffaloes.” And water buffaloes never stray far from the water hole, so you are likely to see me around the West, still learning and thinking about our future on this land.

Jim Holway is director of the Babbitt Center for Land and Water Policy.

Photograph credit: Gisele Grayson, NPR

Nineteen years after it began, a record-setting drought is still choking the Colorado River Basin. The so-called “Millennium Drought” is now recognized as the worst of the past century.

On the rocky walls that hem in Hoover Dam and Lake Mead behind it, the deepening drought can be plainly seen in scaly white “bathtub” rings left behind by the falling water levels. Amazingly, thanks to the river’s massive reservoir system, no one has been forced to go without water—yet. But officials throughout seven U.S. states and Mexico now obsessively monitor mountain snowpack estimates each winter in the hope that the coming year might bring relief.

The drought has haunted water managers not only because it has lasted so long, but also because “things turned really bad really fast—much faster than we thought,” says Jeff Kightlinger, head of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which supplies water to 19 million people in Los Angeles, San Diego, and surrounding areas.

The drought has also brought a series of hard reckonings about the future, and spurred a tremendous amount of soul-searching among those who manage and rely on this river. The unprecedented conditions, along with increasingly available science about the looming impacts of climate change, have forced water managers to contemplate scenarios far outside what they’re comfortable with, and to radically rethink some of their most basic assumptions about the river—beginning with how much water it can actually provide.

Over the past decade and a half, water managers have been in near-perpetual negotiations with each other over how to deal with the drought. The tempo of that process has been relentless, and has, at times, had a distinctly Sisyphean air: Negotiators have been working overtime to stay ahead of the problem, yet the drought presses on.

But something remarkable is happening. The drought has helped bring people together on what has been a famously contentious river. And the so-called “Law of the River”—an accretion of agreements, treaties, acts of Congress, and court rulings often criticized as hopelessly inflexible—may be evolving to meet the hard realities of the twenty-first century.

Throughout much of last year, water managers in the upper and lower Colorado River basins pushed hard to finalize a pair of “drought contingency plans,” referred to collectively as the DCP. They are the biggest and most ambitious effort yet to come to terms with the problems on the river. And yet the DCP will ultimately be just a starting point.

“The DCP, in my mind, is like a tourniquet,” says Kightlinger—an emergency measure to stanch traumatic fluid loss and stave off shock. “We really need to start pulling together a summit of the states, and say, ‘OK, that’s bought us a decade or so—but now we need our 50-year plan. So let’s get to work.’”

Dealing with Drought

Like most of us, Colorado River water managers tend to keep a pretty close eye on their gauges. And the single most important indicator on the river is, for a variety of complicated reasons, the water level in Lake Mead, just outside of Las Vegas.

Although it’s not necessarily intuitive for laypeople, the water level’s elevation above sea level is a proxy for the amount of water in the reservoir. Lake Mead is full when the water level is at roughly 1,220 feet above sea level. “Empty”—or what managers ominously refer to as “dead pool”—lies somewhere around 895 feet.

In 2003, after the severity of the Millennium Drought started becoming apparent, representatives of the seven states that depend on the Colorado—Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming—began meeting to negotiate a plan for softening the blow. Their focus was on holding the water level in Lake Mead at 1,075 feet, or roughly 35 percent of capacity, a level that water managers simply refer to as “ten-seventy-five.” If the level dipped down even more, to about 1,025 feet, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior would likely declare a shortage. Avoiding that declaration is important to the states, because if a shortage is declared and the states can’t agree how to handle it, the federal government has the authority to take over management of the river.

At press time, Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Brenda Burman announced a January 31, 2019 deadline for the states to complete their drought contingency plans. Speaking at the annual Colorado River Water Users Association convention, Burman spelled out the consequences of failing to meet this deadline: the federal government will step in to impose cuts in water deliveries. Five of the basin states have approved their plans; Arizona and California announced they are close and expect to finish before the deadline. “‘Close’ isn’t done,” Burman said. “Only ‘done’ will protect this basin.”

Together, they came up with the so-called 2007 interim shortage guidelines, the first major interstate agreement about how to respond to the drought. Were Lake Mead to fall below ten-seventy-five, Arizona and Nevada (but not, owing to some complicated legal history, California) would cut back their water allocations in three stages, each progressively more drastic.

Taking this step would force the two states to make do with less water in any given year. But it would also slow the decline in Lake Mead and reduce, or at least delay, reaching more severe drought levels.

The plan included several measures intended to keep Lake Mead above ten-seventy-five for as long as possible. That effort has worked—but just barely. Not once since the drought began has Lake Mead sunk below ten-seventy-five. This is in large part because the states and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation have managed to add an extra 23 feet of water to the lake, primarily due to some irrigation districts and tribes agreeing to cut back on their own water use. But for the past four years, the reservoir has been hovering within feet of 1,075 feet. Meanwhile, scientists have released a succession of increasingly dire projections about the long-term impact that climate change will have on Colorado River water supplies.

To better prepare for worsening conditions, the states’ representatives began meeting again to negotiate a new set of drought contingency plans, one for the Upper Basin and one for the Lower Basin. In October, the states, together with the federal Bureau of Reclamation, finally released the draft agreements, which will essentially beef up and expand the 2007 shortage guidelines.

In the Lower Basin, Arizona, Nevada, and California committed to trying to keep Lake Mead above 1,020 feet through the year 2026. To do that, Arizona would progressively reduce its use of Colorado River water by up to 24 percent, a commitment 50 percent bigger than what the state had made under the 2007 guidelines. Nevada agreed to cuts its uses by up to 10 percent, also a 50 percent larger commitment than under the 2007 guidelines. Notably, California—whose Colorado River entitlement is effectively the most senior on the river, and therefore is exempt from reductions under the Law of the River and the 2007 guidelines—has agreed to reduce its use by up to eight percent in any given year by “banking” water in Lake Mead. In exchange, California, along with the two other Lower Basin states, will have new flexibility to recover and use this “banked” water for use within its borders when necessary; until it uses the banked water, any such supply will help keep the reservoir elevation higher. The idea is to delay and, with hope, reduce the severity of potential shortages.

In the Upper Basin, meanwhile, the drought contingency plan will set up a “drought operations agreement” to buttress water levels in Lake Powell—which lies to the north of Lake Mead and is now a little less than half full—by sending water down from reservoirs higher in the basin when necessary. Significantly, the Upper Basin DCP will also open the door to a “demand management program”—similar to an arrangement that has existed in the Lower Basin since the 2007 guidelines—that would allow state or municipal water agencies to pay farmers to temporarily cut back on water use in order to put more water in Lake Powell. The DCP also includes a program to augment river flows through cloud seeding—a technology that can increase precipitation levels and has proven popular in the West—and the eradication of water-thirsty plants like tamarisk.

In the course of these complex negotiations, Mexico pledged that if the seven U.S. states could agree on the DCP, it would reduce its use of Colorado River water by up to eight percent. All told, the twin DCPs will be a major step forward. Yet many observers—and water managers themselves—say they still won’t resolve the biggest problem that’s been haunting the river for decades.

As Doug Kenney, director of the University of Colorado’s Western Water Policy program, puts it: “We’re just using too much water.”

Facing Facts

It’s never been a secret that there wouldn’t be enough water in the river to meet the obligations hammered out among U.S. states, tribes, and Mexico during the twentieth century, and that there would eventually be some hard choices to make. The closest anyone ever got to tackling the issue head-on was in the 1960s, during congressional debates about whether to approve the Central Arizona Project—a massive, 336-mile canal system that diverts water into the southern and central parts of the state—when it became clear that in the future, there would not always be enough water to keep the project’s canals full. But Congress essentially punted, authorizing studies to evaluate ambitious plans to “augment” the flow of the Colorado River through a number of approaches. Those included cloud seeding, desalination of both ocean water and saline groundwater, and “importing” water from other rivers—including an early attempt to target the Columbia River, more than 800 miles away in the Pacific Northwest, an idea that was swiftly beaten back by the Washington congressional delegation.

For the next several decades, the issue went forgotten, for the simple reason that no one needed augmentation. But the conversation has begun to come full circle as demand has grown, the basin has been in a drought cycle, and climate change has diminished supplies. “Inventing augmentation,” says Eric Kuhn, who for decades led the Colorado River Water Conservancy District in western Colorado, “was a way of putting off the pain into the future, and the future is here.”

The first hints that the problem was no longer a purely theoretical possibility came in the mid-1990s, when California, Nevada, and Arizona began running up against the limits of their Colorado River entitlements. The Upper Basin states began worriedly asserting that there was not enough water left for them to ever receive their full entitlements under the Colorado River Compact.

Then came the drought, which transformed these pinch points into actual pain. On top of the drought and usage issues, there’s some basic math making things even more challenging: Each year, massive amounts of water—some 600,000 acre-feet, enough water for nearly half a million people—simply evaporate from Lake Mead. The traditional accounting system under the Law of the River failed to budget for the water lost to evaporation. In addition, Mexico’s share of the river water is simply “deducted” from the shared supply in Lake Mead, rather than being divvied up among the states. Together, evaporation and the Mexico delivery draw roughly 1.2 million acre-feet more water from Lake Mead each year than is released from Lake Powell, upstream—even without a drought.

Under the 2007 shortage guidelines, the Lower Basin states can receive extra water—so-called equalization releases—if river conditions are good enough. But “in most years, we’re still going to have a deficit at Mead of a million or more acre-feet,” says Terry Fulp, the federal Bureau of Reclamation’s Lower Colorado regional director.

That imbalance has come to be known as “the structural deficit,” and it lies at the heart of the Colorado River’s problems. “It’s a code word, in my mind, for overallocation,” says Fulp. “We’ve got an absolutely overallocated system.”

Untangling this problem will be key to long-term sustainability on the river. It will also be a tremendous challenge—and tremendously expensive. The 23 feet of water the states have managed to add to the water level in Lake Mead since the DCP negotiations began has cost at least $150 million.

That slug of extra water is “important when you’re right at the threshold,” says Kenney of the University of Colorado. But in the bigger picture, he says, “it’s a terribly small amount of water, and it’s a terribly big price tag.” Truly stabilizing the system will require much bolder action, and will cost far more.

Beyond DCP

So what might efforts beyond DCP actually look like?

“You’ve got to be focused on reducing the absolute load on the system,” says Peter Culp, an Arizona attorney who advises both the City of Phoenix and several environmental nongovernmental organizations. But because of wild swings in natural variability like the current drought, he says, “you also need to be prepared to deal with high levels of instability.”

As the states begin to look at longer-term solutions, several broad possible components seem likely to come to the fore:

Augmentation

Today, the term has a far more modest connotation than it did in the 1960s, when vast water-importation plans and massive nuclear-powered desalination plants seemed within the realm of feasibility. Conventionally powered desalination of seawater is now the augmentation option cited most frequently, although the sole operating example is the Poseidon desalination plant that serves San Diego. It produces a relatively modest 56,000 acre-feet per year at a cost double that of water supplied from the Colorado River (Hiltzik 2017). Cloud seeding—artificially induced rainfall—has been carried out for decades, but has only limited effectiveness.

“Augmentation is part of the portfolio,” says Chuck Cullom, the Central Arizona Project’s Colorado River programs manager, “but there aren’t, and have never been, any silver bullet answers.” Augmentation projects, he says, “are all going to be hard-fought, challenging, modest-sized—and more expensive than we thought.”

Markets, Leasing, and Transfers

The ability to move water between water-rights holders will play a huge role in increasing the flexibility needed to weather the looming problems on the river. Although there are still gains to be made in urban water-use efficiency (think reduced water use for grass and landscaping), the water needs of the West’s 40 million, primarily urban, individual water users are relatively inelastic. A discussion is slowly taking shape about ways in which cities can make deals to acquire water from both native tribes and farms in a way that doesn’t threaten the survival of any of those three sectors.

Tribal Rights

Local tribes will likely play a bigger role in meeting future demands, particularly in Arizona, where their right to significant amounts of water has recently been affirmed. “The tribes are increasingly important political players, and they are increasingly important in this idea of leasing and flexibility within the existing rules,” says Dave White, who heads Arizona State University’s Decision Center for a Desert City, which is largely focused on finding ways to help policy makers make better decisions about uncertain futures. “That makes them an important lynchpin in moving from the current allocation system to the future one.” Tribes have rights to an estimated 2.4 million acre-feet of Colorado River water (Pitzer 2017).

Daryl Vigil is the water administrator for the Jicarilla Apache Nation in New Mexico and is head of the Ten Tribes Partnership, which has long pushed for the ability to lease its members’ water to other users. Vigil says that in an era of drought and climate change, tribal water can help cities and other users stabilize their water-supply portfolios while securing much-needed revenue. “Right now, there are tribes that, because of infrastructure issues or policy issues, aren’t able to develop their water rights, so it’s just going downstream” and being used by non-tribal entities without compensation, Vigil says. “To a large degree, we’re already the solution to a lot of these issues, but we’re not getting any kind of credit for it.”

Some tribes have already been able to parlay their water rights into revenue. The Jicarilla Apache tribe, for example, leases water to the federal Bureau of Reclamation to provide minimum river flows for endangered fish, and in 2017 the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona struck a deal with the Bureau, the City of Phoenix, and the Walton Family Foundation to lease its water in order to boost levels in Lake Mead.

Agriculture

Farms will also play a big role in a more comprehensive solution on the river. Agriculture accounts for around 75 percent of water use in the basin, the vast majority of which is used to grow forage and pasture, like alfalfa, for beef and dairy cattle. Farm water supplies could potentially be used for farm-to-city water transfers, or to help cushion the impact of temporary shortages on cities.

In fact, the framework for agricultural-to-urban water transfers on the Colorado River was first created in the late 1990s. The years since have seen a series of test runs and a slow expansion of the concept throughout the Lower Basin and even across the border to Mexico. The terms of the 2007 interim shortage guidelines allow irrigation districts in Arizona, California, and Nevada to “forbear”—that is, to forgo the use of a portion of their water allocation for a year, thereby freeing up water to be stored in Lake Mead for drought protection. The proposed Demand Management Program included in the Upper Basin drought contingency plan would open the door to a similar framework there.

Water for such programs can be generated in a variety of different ways: simply by fallowing farmland (i.e., taking it out of production), thereby freeing up the water that otherwise would have been used to grow crops there; by switching to crops that consume less water; or by improving irrigation efficiency and transferring the conserved water. Although transferring water away from farms is, in the public imagination, often equated with drying up farms and putting them out of business, there is a long history of innovative thinking about how farms can generate water for uses elsewhere while remaining financially viable. In California, for instance, the Palo Verde Irrigation District has been the focus of a long-running “rotational fallowing” program to generate water for the Metropolitan Water District, under which at most 29 percent of the irrigation district’s farmland is fallowed in any given year.

The transfer of water from farms to cities, either temporarily or permanently, is an extremely controversial issue. Any discussion of the topic—especially in Arizona, where farmers would be the first to have their water cut due to contractual agreements made well before the current negotiations began—quickly moves from technical talk of crop consumptive water-use coefficients to basic questions of social equity.

“That’s the crux of the problem: Do people perceive that the pain is distributed fairly?” says Cullom. The drought and the contingency-planning process, he says, are forcing people to come to terms with “the visceral understanding of what a future with less water looks like.”

Win, Lose, or Draw

Back in the early 1990s, a consortium of university researchers used computer models to simulate a “severe and sustained drought” on the river, in an effort to see how water users might respond. The simulated drought used in the exercise would ultimately prove to be eerily similar to the Millennium Drought that took hold less than a decade later. But at the time, notes Brad Udall, a senior water and climate research scientist at Colorado State University, barely any water managers bought into the drought-simulation effort. “The academics wanted to go push all this stuff, but they couldn’t get any decision makers to participate,” he says. “Nobody wanted to lay their cards out.”

If there’s one up side to a 19-year drought, it may be that it has opened up conversations that wouldn’t otherwise be happening. The players are increasingly willing to lay their cards on the table. And the past 19 years have shown that some problems on the Colorado can be addressed, for better or worse, not through radical change but through incrementalism, with the stakeholders gradually playing one hand after another.

But now the stakes are getting higher. Even as representatives of the seven states were in the midst of negotiating the drought contingency plans, climate scientists were delivering more bad news: The Colorado River Basin may be on the brink of a permanent shift into a much drier reality. In 2017, Udall and Jonathan Overpeck, now the dean of the University of Michigan’s School for Environment and Sustainability, found that increasing temperatures could cause the flow of the Colorado River to decline by more than 20 percent at mid-century and 35 percent at the end of the century.

“I don’t care what level of demand management you do,” says Arizona attorney Culp, “that’s a really big problem.”

The states’ negotiators will not get much reprieve before they have to tackle the next round of even tougher questions: The provisions of both the 2007 shortage guidelines and the arduously negotiated DCP will expire in 2026, and the states have agreed on the need to open negotiations for a follow-on agreement just a year from now, in 2020. That next phase will likely serve as the forum for tackling the bigger issues on the river.

“We have to find a way to permanently reduce our demands, and find a way to augment our supply,” says Kightlinger of California’s Metropolitan Water District. That effort, he says, won’t be fast or easy— and Dave White of the Decision Center for Desert City suggests it might require “recalibrating the entire system to what we think is the new availability of water.”

Are people willing to commit to a recalibration or radical overhaul of the way the river is managed, or will they simply adopt a more ambitious follow-on to the operational “updates” of the 2007 interim shortage criteria and the drought contingency plan? A wholesale revamp of the Law of the River—what Fulp calls “the start-over scenario”—is politically taboo for water managers.

Yet the DCP may be the first step in subtly steering everyone into that difficult conversation. The emphasis on tackling “drought”—rather than overuse—may have been a considered move on the part of negotiators. “Politically speaking, I think it’s a useful word for the states,” says Kenney. “To the extent that you talk about drought contingencies and shortage, you’re talking about what we’re going to have to do in an emergency.”

The message, he says, is that “the drought is getting really bad, and we have to make some adjustments. But”—at a time when the Colorado River states are running up against the limits of their allocations—“the reality is that it doesn’t take an emergency to get you to shortage. It doesn’t take an emergency to crash the systems. Just business as usual crashes the system” if the drought worsens.

In spite of calls for radical reform on the river, the key to a durable solution—which may ultimately be just as important as a comprehensive solution—could, paradoxically, be to go slow. “Incrementalism allows people to get comfortable with changes a little bit at a time,” says Kuhn of the Colorado River Water Conservancy District. “And I actually think the incremental change will happen as fast as necessary to adapt to the real-world conditions.”

That approach is obviously not without its risks. The primary result of all the negotiations that have occurred since 2003, which have all but consumed the lives of those involved in them, is that water managers have so far managed to push off a shortage declaration by the federal government by just three years. If negotiators continue to work incrementally, will they be able to keep pace with how quickly the system is changing?

No one knows, and the river isn’t telling. But for now, the DCP process has bought everyone a little time to catch their breath. “[DCP] will get the risk back down,” says Fulp. “It will give us that time to really open up the dialogue on much bigger, and much more difficult, issues.”

On the Colorado River, Change Is the Constant

After nearly 16 years of negotiations, water managers seem to have staved off disaster—for now. Will the next round of negotiations, which begins in 2020, be able to keep pace with how quickly the Colorado River system and conditions in the basin are changing? Dr. Jim Holway of the Babbitt Center for Land and Water Policy thinks it’s going to take significant change. “I believe we will need institutional, policy, and infrastructure changes to sustainably manage the river,” Holway says. Citing challenges including climate change, highly variable conditions, population growth, conflicts over the Law of the River, and increasing water costs, Holway explains that the Babbitt Center exists to recognize and address these challenges, with a particular focus on connecting land use decisions and sustainable water management at the local level. Looking beyond 2026, when both the interim shortage guidelines of 2007 and the proposed DCP modifications expire, Holway identifies a central question: “How do we best prepare for this future, and how do we ensure our policies and decision makers at every level are up for the challenge—and able to quickly adapt as conditions change?”

Matt Jenkins has been covering the Colorado River since 2001, primarily as a longtime contributor to High Country News. He has also written for The New York Times, Smithsonian, Men’s Journal, Grist, and numerous other publications.

Photograph: Fishing boat in the Colorado River Delta. Credit: Pete McBride

References

Hiltzik, Michael. 2017. “As Political Pressure for Approval Intensifies, the Case for a Big Desalination Plant Remains Cloudy.” Los Angeles Times, May 19, 2017. http://www.latimes.com/business/hiltzik/la-fi-hiltzik-desalination-20170521-story.html.

Pitzer, Gary. 2017. “The Colorado River: Living with Risk, Avoiding Curtailment.” Western Water, Fall 2017. https://www.watereducation.org/western-water-excerpt/colorado-river-living-risk-avoiding-curtailment.

The desert city of Tucson, Arizona, has an average annual rainfall of just 12 inches. But when the rain comes, it often comes in the form of torrential downpours, causing damaging floods across the city. This is a perhaps ironic challenge for Tucson and the broader Pima County area in which it is situated, given that it’s part of a much larger region working to ensure that there is—and will continue to be—enough water to go around in a time of unrelenting drought.

Both of these distinct water-management challenges—too dry and too wet—can be addressed by thoughtful land use and infrastructure decisions. Of course, when making such decisions, it helps to have precise mapping data on hand. That’s why Pima County officials are working with the Lincoln Institute’s Babbitt Center for Land and Water Policy and other key partners to pilot the use of some of the most cutting-edge mapping and data analysis tools on the market.

For the Babbitt Center—founded in 2017 with the mission of providing land-use research, education, and innovation to communities throughout the Colorado River Basin—the partnership represents one early step in exploring how such technology can be used to help integrate water and land use management across the region.

The technology itself originated across the country, at the Conservation Innovation Center (CIC) of Maryland’s Chesapeake Conservancy, a key player in cleaning up the notoriously pollution-addled Chesapeake Bay. To oversimplify a bit: CIC has designed image analysis algorithms that provide distinctly more granular image data of the earth’s surface. The technology has enabled a shift from a resolution that made it possible to observe and classify land in 30-meter-square chunks to a resolution that makes that possible at one square meter.

The details are of course a little more complicated, explains Jeffrey Allenby, the Conservancy’s director of conservation technology. Allenby says the new technology addresses an historic challenge: the compromise between resolution and cost of image collection. Until relatively recently, you could get 30-meter data collected via satellite every couple of weeks or even days. Or you could get more granular data collected via airplane—but at such a high cost that it was only worth doing every few years at most, which meant it was less timely.

What’s changing, says Allenby, is both the camera technology and the nature of the satellites used to deploy it. Instead of launching a super-expensive satellite built to last for decades, newer companies the CIC works with—Allenby mentions Planet Labs and DigitalGlobe—are using different approaches. “Smaller, replaceable” satellites, meant to last just a couple of years before they burn off in the atmosphere, can be equipped with the latest camera technology. Deployed in a kind of network, they offer coverage of most of the planet, producing new image data almost constantly.

Technology companies developed this business model to respond to commercial and investor demand for the most recent information available; tracking the number of cars in big-box store parking lots can, in theory, be a valuable economic indicator. Land use planners don’t need images quite that close to real time. But Allenby says the CIC began asking the tech companies, “What are you doing with the imagery that’s two weeks old?” It’s less expensive to acquire, but far better than what was previously available. The resulting images are interpreted by computers that classify them by type: irrigated land, bedrock, grassland, and so on. Doing that at a 30-square-meter level required a lot of compromise and imprecision; the one-meter-level is a different story.

The goal is to “model how water moves across a landscape,” as Allenby puts it, by combining the data with other resources, most notably LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) elevation data. Those are the “flour and eggs” of land use data projects, supplemented with other ingredients like reduction efficiencies or load rates from different land cover, depending on the project, Allenby says: “We’re building new recipes.” For Chesapeake Bay, those recipes are meant to help manage water quality. If you can determine where water is concentrating and, say, taking on nitrogen, you can deduce the most cost-effective spot to plant trees or place a riparian buffer to reduce that nitrogen load. (See “Precision Conservation,” October 2016 Land Lines.)

In the Colorado River Basin, the most urgent current water-management challenges are about quantity. Since water policy is largely hashed out at the local level despite the underlying land use issues having implications across multiple states, the Babbitt Center serves as a resource across a broad region. There’s currently a “heightened awareness” of water management among municipal and county policy makers, says Paula Randolph, the Babbitt Center’s associate director. “People are wanting to think about these issues and realizing they don’t have enough information.”

That brings us back to Pima County. Although it lies outside the basin, it boasts two features that make it a good place to evaluate how the uses of precision mapping data might be applied in the West: Basin-like geography and proactive municipal leaders. When the manager of technology for the Pima Association of Governments saw Allenby speak about the benefits of his work in the East, he contacted the CIC to discuss possibilities for the West. A year into the resulting project, several partners are on board, the group is mapping a 3,800-square-mile area, and the open-source data lives on the Pima Regional Flood Control District website, where others throughout the county are able to access and use it.

Broadly, this process has taken some effort, Randolph notes. Satellite data gathered in the West has different contours than the East Coast imagery that Chesapeake’s sophisticated software was used to, and that has required some adjustment—“teaching” the software the difference between a Southwestern rock roof and a front yard that both look (to the machine) like dirt. “We need human partners to fix that,” she says. “We strive for management-quality decision-making data.”

Even as such refinements continue, there are already some early results in Pima County. Clearer and more precise data about land cover is helping to identify areas that need flood mitigation. It has also been useful to identify “hot spots” where dangerous heat-island effects can occur, offering guidance for mitigation actions like adding shade trees. These maps provide a visual showcase about water flow and land use more efficiently than a field worker could.

Both Allenby and Randolph stress that this partnership is still in the early phases of exploring the potential uses and impacts of high-resolution map data. Randolph points out that while the Babbitt Center is working on this and another pilot project in the Denver area, the hope is that the results will contribute to a global conversation around water-management experimentation.

And Allenby suggests that the “recipes” being devised by technologists, policy makers, and planners will ideally lead to a shift in more accurately evaluating the efficiency and impact of various land use projects. This, he hopes, will lead to the most important outcome of all: “Making better decisions.”

The Lincoln Institute has provided occasional financial support to the CIC for map- and data-related projects.

Rob Walker (robwalker.net) is a columnist for the Sunday Business section of The New York Times.

Image: High-resolution land cover data offers a closer look at Tucson, Arizona. Credit: Chesapeake Conservancy.

For six centuries, a people called the Hohokam inhabited central Arizona. Among their many accomplishments, they created a hydraulic empire of sorts, a spiderlike web of canals intended to deliver water from the Gila and Salt rivers—tributaries of the mighty Colorado—to their agricultural fields. Eventually, the Hohokam abandoned their fields and canals. To this day, the reason is uncertain, but historian Donald Worster once surmised that the productive but ill-fated tribe “suffered the political and environmental consequences of bigness” (Worster 1985).

Bigness. It’s the perfect word to describe not only the Colorado River Basin, but so much of the geography, history, culture, politics, and challenges associated with it.

In its sheer complexity, the Colorado stands out among the rivers of America, and probably the world. In this river basin of 244,000 square miles, one-twelfth the land mass of the continental United States, exist great diversities, places of oven-hot heat and icy vastness. All but 2,000 of those square miles lie in the United States. Just 10 percent of that land mass, mostly in an elevation band of 9,000 to 11,000 feet in the Rocky Mountains, produces 90 percent of the water in the system.

Hydraulic infrastructure abounds at almost every turn on the river’s 1,450-mile journey. The first diversions occur at its very headwaters in Rocky Mountain National Park, before the river can rightfully be called a creek. Fourteen dams have been erected on the Colorado River, and hundreds more on its tributaries. Hoover Dam, perhaps the best known, hulks a half-hour drive from Las Vegas. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) built it in the 1930s to hold back the river’s spring floods, creating a reservoir now known as Lake Mead. A second massive reservoir, Lake Powell, lies upstream 300 miles. It’s the result of Glen Canyon Dam, built in the 1960s with the goal of providing a means for the four Upper Basin states—Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming—to store the water they had agreed to deliver to the Lower Basin states of Arizona, California, and Nevada, and to Mexico.

At their fullest, the two reservoirs—which are the biggest in the country—can hold four years of flows of the Colorado River. A recent paper suggested that the two reservoirs could be considered one giant reservoir, bisected by a “glorious ditch” (CRRG 2018). That ditch is the Grand Canyon, which celebrates the one hundredth anniversary of its designation as a national park this year.

The dams, reservoirs, tunnels, and aqueducts of the Colorado deliver water to 40 million people in seven U.S. states—more than 1 in 10 Americans—and two Mexican states. The river’s water also nourishes more than 5.5 million acres of agricultural fields within and outside the river basin. Residents of Denver, Los Angeles, and other cities outside the basin rely on the river; crops in fields reaching almost to Nebraska benefit from transbasin exports and diversions.

The river provides a cultural and economic resource for 28 tribes within the basin. A $1.4 trillion economy hums along in and around the basin. This includes the snowmaking cannons at Vail and Aspen, the nightly water spectacle at the Bellagio in Las Vegas, and the aeronautics industry of Southern California. Up and down the river, more than 225 federal recreation sites draw visitors eager to try their luck at fishing, rafting, hiking, or just taking in the sights. This river and the lands around it loom large in the public imagination.

It’s a big, complicated, and now vulnerable hydraulic web. Entering the twenty-first century, the river was already a sponge fully squeezed, its water rarely making it to the Gulf of California.

Rapid population growth, rising temperatures, and declining river flows are putting pressure on the system, forcing river managers and users to devise creative, forward-looking plans that consider both water and land. The Lincoln Institute’s Babbitt Center for Land and Water Policy strongly encourages this approach. “We are trying to think more holistically by considering the management and planning of land and water resources together,” says Babbitt Center Program Manager Faith Sternlieb. “These are the foundations upon which water policy in the Colorado River Basin has been considered and crafted, and these are the roots we must nurture for a sustainable water future.”

Taming the Colorado

The need to nurture roots has driven the development of the Colorado River Basin since the first people began farming there. The Hohokam, Mojave, and other tribes built canal systems of varying complexity to irrigate their fields. In the late 1800s, federal interest in tapping the river to boost agricultural production surged. By 1902, the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) had created what is now the Bureau of Reclamation. During the twentieth century, the Bureau became the prime builder, and funder, of agricultural water projects throughout the basin.

Work on the Laguna Diversion Dam, the first dam on the Colorado River, began in 1904, yielding water a few years later for fields near Yuma, Arizona. Yuma sits in the Mojave Desert, where Arizona, California, and Mexico come together. There, long, nearly frost-free growing seasons coupled with fertile soils and Colorado River water enable extraordinary productivity. Today, farmers in the Yuma area of Arizona and Imperial Valley of California proclaim that during winter they grow 80 to 90 percent of the greens and other vegetables in the United States and Canada. This area, declares Arizona’s Yuma County Agriculture Water Coalition, is to U.S. agriculture what Silicon Valley is to electronics and what Detroit was to automobiles (YCAWC 2015).

All told, irrigation accounted for 85 percent of total water withdrawals in the basin between 1985–2010 (Maupin 2018). Today, agriculture still accounts for 75 to 80 percent of total water withdrawals. This supports row crops such as corn and the perennial crop of alfalfa, which is grown from Wyoming to Mexico. Much of the crops go to livestock: The Pacific Institute, in a 2013 report, estimated that 60 percent of agricultural production in the basin feeds beef cattle, dairy cattle, and horses (Cohen 2013). Agriculture has always been, and will remain, a key piece of the Colorado River puzzle.

But almost as quickly as the Bureau of Reclamation began diverting water for agriculture, other needs arose, from producing electricity to slaking the thirst of booming Los Angeles. By the early 1920s, the seven states of the arid West realized they had to find a way to share a river that would become—as the river’s preeminent historian, the late Norris Hundley, would later write—“the most disputed body of water in the country and probably in the world” (Hundley 1996). Years later, Hundley famously referred to the area as a “basin of contention” (Hundley 2009).

Today, dozens of laws, treaties, and other agreements and rulings collectively called the Law of the River govern the use of Colorado River Basin water. They include federal environmental laws, a treaty over salinity, amendments to treaties, a U.S. Supreme Court case, and interstate compacts. None is more fundamental than the Colorado River Compact of 1922, which still guides the annual share of water each state gets. Representatives of the seven basin states hammered out its provisions in grueling meetings held near Santa Fe. They were driven by both ambition and fear.

Ambitious California needed federal muscle to tame the Colorado River if it was to realize its agricultural potential. Los Angeles had aspirations, too. In the century’s first two decades, it had grown more than 500 percent and wanted the electricity that a large dam on the river could deliver. A few years later, it also decided it wanted the water itself. To pay for this giant dam, California needed federal help. Congress would approve that aid only if California had secured support from the other southwestern states.

Fear drove the other basin states. If the first-in-time, first-in-right legal system of prior appropriation used by Western states was to be applied to the Colorado River, California and perhaps Arizona would reap the benefits. The headwaters states, including Colorado, were developing too slowly to benefit from their own long and snowy winters. Delph Carpenter, a Colorado farm boy turned water lawyer, forged the consensus. Both basins, upper and lower, got 7.5 million acre-feet, for a total of 15 million acre-feet. Mexico needed water, too, which the compact assumed would come from surplus waters. A later treaty between the two nations specified 1.5 million acre-feet for Mexico.

The 1922 Colorado River Compact also nodded, but no more, at what later writers called a sword of Damocles hanging over these allocations: water for the basin’s Indian reservations. The U.S. Supreme Court, in a 1908 case called Winters v. United States, had declared that when Congress reserved land for a reservation, it implicitly reserved water sufficient to fulfill the purpose of that reservation, including agriculture. That ruling did not determine the amounts that were needed. Tribal water rights within the basin now constitute 2.4 million acre-feet, in many cases senior in priority to all other users within the allocations of the individual states. That’s a fifth of the river’s total flows. Importantly, specific water allocations for some of the largest tribes still have not been resolved.

The framers of the 1922 compact made a big, fatally flawed assumption: That enough water existed to meet everyone’s needs. Average annual flows from 1906 to 1921 had averaged 18 million acre-feet. But even by 1925, just three years after the Compact came into being and three years short of its Congressional approval, a U.S. Geological Survey scientist named Eugene Clyde La Rue had delivered a report indicating the river probably would deliver too little water to meet these hopes and expectations. Other studies about the same time delivered the same conclusions.

They were right. Over a longer period, from 1906 to 2018, the river has averaged 14.8 million acre-feet per year. Averages have dropped during the twenty-first century, in the midst of a 19-year drought, to 12.3 million acre-feet. In the last water year, ending in September 2018, the river carried only 4.6 million acre-feet. That’s just 200,000 more acre-feet than California’s annual entitlement.

The Shift from Farms to Cities

Agriculture was the main driver of development along the Colorado River. According to a recent report from the U.S. Geological Survey, 85 percent of water withdrawals went toward irrigation between 1985 and 2010 (Maupin 2018). The fields around Yuma, Arizona, and the Imperial and Palo Verde valleys of California consume more than 4 million acre-feet of Colorado River water annually, nearly a third of the river’s annual flows. But with population growth, water use has shifted to urban needs.

In Colorado, for example, 95 percent of water imported from the Colorado River headwaters through the Colorado-Big Thompson (CBT) project was once used for agriculture; now, that number is closer to 50 percent. As another example of the complexity of systems in the Colorado River Basin, CBT water is divided into units which can be bought and sold. The amount of water in a unit varies year to year depending on the total amount of water available; when CBT is at full capacity, a unit is one acre-foot. Agricultural users owned 85 percent of the units when trading began in the late 1950s, but currently own less than one-third of available units. Municipalities own the balance, but often lease the water to farms until it’s needed. The current price for a CBT unit is close to $30,000.

Such water-sharing agreements are becoming more common in a system stretched too thin. Rotational fallowing, also known as lease-fallowing or alternative-transfer mechanisms, has played a role in shifting water from farms to cities. Farmers in the Palo Verde Valley struck a deal with the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which serves 19 million customers, to fallow between 7 and 35 percent of their land on a rotating basis. Metropolitan’s customers, in turn, get the water, which can be stored in Lake Mead. Similar deals, still underlined with tension but increasingly accepted, exist between Southern California municipalities and farmers in the Imperial Valley and between cities and farmers along Colorado’s Front Range urban corridor.

For their part, cities tend to tout conservation and development efforts they’ve made with water in mind. Many are encouraging density, reducing the water needed for landscaping; some have implemented turf-removal programs; and toilets, showers and other fixtures have become more efficient. Metropolitan Water District of Southern California chalked up a 36 percent per capita reduction in water use from 1985 to 2015, a time of several droughts, according to Planning magazine (Best 2018).

In Nevada, the population served by the Southern Nevada Water Authority has increased 41 percent since 2002, but the per capita consumption of Colorado River water fell 36 percent. The agency’s Colby Pellegrino, speaking at a September 2018 conference called “Risky Business on the Colorado River,” said conservation is the first, second, and third strategy for achieving reduced water consumption. “If you live in the Las Vegas Valley, where there is less than 4 inches of rainfall a year, and you have a median covered in turf, and the only person walking on that turf is the person pushing a lawn mower—that is a luxury our community cannot afford, if we want to continue to have the economy we have today,” she said.

Economy, culture, and values have been at the core of the basinwide debate about how to respond to the drought. No one sector or region can absorb the full burden of necessary reductions, and it’s clear that everyone must begin to think differently. Speaking at the “Risky Business” conference, Andy Mueller, general manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District, put it this way: Instead of the intentional use of water, Colorado is now talking about the intentional non-use of water. As is everyone who lives and works in the Colorado River Basin.

A River Shared

In late 1928, Congress approved the Boulder Canyon Project Act. This legislation accomplished three significant things: It authorized construction of a dam in Boulder Canyon, near Las Vegas, which was later named Hoover Dam. The law also authorized construction of the All American Canal, crucial for developing the productive farmland of California’s Imperial Valley, an area that’s now the single largest user of Colorado River water. And the Boulder Canyon Project Act divided waters among the Lower Basin states: 4.4 million acre-feet each year to California, 2.8 million acre-feet to Arizona, and 300,000 acre-feet for Nevada. Las Vegas then had a population of fewer than 3,000 people.

As the twentieth century rolled on, headwaters states also got dams, tunnels, and other hydraulic infrastructure. In 1937, Congress agreed to bankroll the Colorado-Big Thompson Project, what historian David Lavender called a “massive violation of geography” intended to divert Colorado River waters to farms in northeastern Colorado, outside of the hydrological basin. In 1956, Congress approved the Colorado River Storage Project Act, authorizing a handful of dams, including Glen Canyon.

Only Arizona remained left out. It had vigorously opposed the 1922 compact, then remained defiant. Its Congressional representatives opposed Hoover Dam and, in 1934, then-Governor Benjamin Moeur even dispatched the state’s National Guard in a showy opposition to construction of another dam being built downstream to deliver water to Los Angeles. “Put simply, Arizonans feared there would be little water remaining for them after the Upper Basin, California, and Mexico got what they wanted,” Hundley explains (Hundley 1996). Finally, in 1944—the same year the U.S. and Mexico reached an agreement about the amount of water due to the latter—Arizona legislators succumbed to political realities. Cooperation, not confrontation, would be needed for the state to get federal help to develop its share of the river. At last, the compact had the signatures of all seven states.

Arizona finally got its big slice of Colorado River pie in the 1960s. A U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1963—one in a series of Arizona vs. California cases over many decades—confirmed Arizona had the right to 2.8 million acre-feet, as Congress had specified in 1928, along with all the water in its own tributaries. This is what Arizona had wanted all along. In 1968, Congress approved funding for the massive Central Arizona Project, ultimately resulting in the construction of 307 miles of concrete canal to deliver water from Lake Havasu to Phoenix and Tucson and farmers between. California supported the authorization, with a hitch: In times of shortage, it would still have rights to its 4.4 million acre-feet first. This led Arizona to later create a water banking authority to store Colorado River in underground aquifers, providing at least partial security against future shortages.

Upper Basin states had reached accord about how to apportion their 7.5 million acre-feet without notable friction: Colorado 51.75 percent, Utah 23 percent, Wyoming 14 percent, and New Mexico 11.25 percent. They used percentages, as Hundley explained, because of “uncertainty over how much water would remain after the upper basin had fulfilled its obligation to the lower-basin states” and Mexico. Fluctuations in the river’s flow, they reasoned, might mean that some years they had an amount smaller than 7.5 million acre-feet to divide between themselves. It was, in retrospect, an eminently wise decision.

Conservation Concerns

The same year the basin states framed the original Colorado River Compact, the great naturalist Aldo Leopold canoed through the Colorado River Delta in Mexico. In an essay later published in A Sand County Almanac, he described the delta as “a milk and honey wilderness.” The river itself was “nowhere and everywhere,” he wrote, and was camouflaged by a “hundred green lagoons” in its leisurely journey to the ocean. Six decades later, visiting the delta after a half-century of feverish engineering, construction, and management had emerged to put the river’s waters to good use, the journalist Philip Fradkin had a different take. He called his book A River No More.

As the 20th century closed, the environmental impacts of essentially regarding a river as plumbing drew new attention, especially in the now dewatered delta. The lagoons that had so enchanted Leopold were gone, because the stopped-up river no longer reached its southern outlet. Drainage from vast agricultural enterprises had made the river so saline that, among other things, Mexico protested that the water it was receiving was unfit to use. The many dams and diversions that came after Leopold’s visit had also put 102 river-dependent rare birds, fish, and mammals on the brink of extinction, reported the Arizona Daily Star. The newspaper lauded the work of stakeholders in a new transborder conservation effort: “The fundamental principle of ecology calls for land managers to look to the good of the whole system, not just its parts.”

Environmental groups might have used the Endangered Species Act to force the argument about solutions, but the delta was not within the United States. So they looked to find collaborative solutions. In the closing days of the tenure of Bruce Babbitt, secretary of the Interior in the Clinton administration and namesake of the Babbitt Center, the two countries adopted Minute 306. It created the framework for a dialogue that produced, under Babbitt’s successors in the Bush administration, an agreement called Minute 319 and a one-time pulse flow of more than 100,000 acre-feet in the river in 2014.

Children gleefully splashed in the rare waters of the river in Mexico during that pulse flow, but adults on both sides of the border were equally happy. Among those grinning was Jennifer Pitt, then of the Environmental Defense Fund. Litigation had been a possible route, she said, but an inclusive and transparent process with stakeholders was more productive.

“The institutional legal and physical framework we have on the Colorado River is the basis for great competition and the potential for litigation between parties,” says Pitt, who is now with Audubon. “But it is exactly that same framework that has given those parties the opportunity to collaborate as an alternative to having solutions handed to them by a court.”

Collaboration Is Critical

Reservoirs were full as the next century arrived, thanks to robust snowfall in the Rockies during the 1990s. Still, there was tension. California for decades had exceeded its apportionment of 4.4 million acre-feet, consuming a high of 5.4 million acre-feet in 1974. Upper Basin states never have fully developed their 7.5 million acre-feet, averaging 3.7 to 4 million since the 1980s, plus 500,000 acre-feet from reservoir evaporation.

Then came drought, deep and extended. The river carried just 69 percent in 2000. The winter of 2001 to 2002 was even more stingy, the river delivering just 5.9 million acre-feet, or 39 percent of average, at Lake Powell. From 2000 to 2004 was the lowest 5-year cumulative flow in the observed record. Since then, more years have been dry than wet. The reservoir levels are at near-record lows.

The 1922 compact had not contemplated this kind of long-term drought. A structural deficit came into sharp relief. Tom McCann, assistant general manager of the Central Arizona Project, coined the phrase. Very simply, the Lower Basin states were using more water than was delivered from Lake Powell each year. This was so even when the Bureau of Reclamation authorized the release of extra “equalization” flows from Powell.

“Equalization releases are like hitting the jackpot on the slot machine,” McCann says. “Back then, we were hitting the jackpot every three or four or five years, and we thought we had nothing to worry about.” Even with the jackpots, Lake Mead continued to decline, the reservoir’s widening bathtub ring charting the losses.

Climate change overlays the structural deficit. Scientists argue that warming temperatures swing a big bat in the Colorado River Basin. They term the early-twenty-first-century declines a “hot drought” as distinguished from a “dry drought.”