This article is excerpted from a forthcoming Lincoln Institute Policy Focus Report, Rethinking the Property Tax–School Funding Dilemma, and from a Lincoln Institute working paper, “Effects of Reducing the Role of the Local Property Tax in Funding K–12 Education.”

The massive shutdown of K–12 schools sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic has no precedent in U.S. history. By the end of the 2019–2020 school year, at least 50.8 million public school students had been affected by school closures (Education Week 2020). Although schools closed during the 1918 influenza pandemic, fewer children attended school then and schools were not as integral to daily life (Sawchuk 2020). This time, almost overnight, the national education system shifted dramatically. Teachers were required to adapt lessons to virtual meeting platforms. The forced rapid transition to online methods led to learning loss or unfinished learning for many students. The pandemic exacerbated existing disparities and created new challenges for students of color, English language learners, and students with disabilities.

The pandemic also sparked a temporary shift in national education funding as the country experienced one of the deepest economic downturns in its history. Vigorous federal fiscal policy helped make it the shortest recession in the country’s history as well, and as part of this economic rescue effort, Congress funneled hundreds of billions of dollars to education. These funds came via the March 2020 CARES Act; a second infusion sent to state and local governments in December 2020; and the American Rescue Plan Act of March 2021, which contained another $350 billion for state and local governments plus about $130 billion specifically for K–12 education. Altogether in the first year of the pandemic, the federal government provided an unprecedented amount of aid for public K–12 education, equivalent to about $4,000 per student (Griffith 2021).

Although this lessened the fiscal impact of the pandemic in the near term, it did not permanently alter the federal government’s traditionally modest role in funding K–12 education. Public schools are typically supported by a combination of state aid and local funding. The property tax has been the single largest source of local revenue for schools in the United States, reflecting a strong culture of local control and a preference for local provision.

An Ideal Local Funding Source

Property taxation and school funding are closely linked in the United States. In 2018–2019, public education revenue totaled $771 billion. Nearly half (47 percent) came from state governments, slightly less than half (45 percent) from local government sources, and a modest share (8 percent) from the federal government. Of the local revenue, about 36 percent came from property taxes. The remaining 8.9 percent was generated from other taxes; fees and charges for things like school lunches and athletic events; and contributions from individuals, organizations, or businesses.

In many ways, the property tax is an ideal local tax for funding public education. In a well-structured property tax system, without complex or confusing property tax limitations, the tax is both visible and transparent. Voters considering a local expenditure, such as for a new elementary school, will have clear information on benefits and costs. The property tax base is immobile; by contrast, shoppers can easily avoid a local sales tax by driving a few miles and businesses can avoid liability for local income taxes by relocating office headquarters.

The property tax is also a stable tax, as evidenced by its performance relative to the sales tax and income tax each time the economy falls into a recession. Since state governments rely predominantly on sales and income taxes, states often cut aid to schools in recessions in order to balance their budgets. This means that in most recessions public schools increase their reliance on property tax revenues to make up for declining state school aid (see figure 1).

But the property tax as a source of school funding has not been without controversy. In the 1970s, public recognition that disparities in the relative size of local tax bases can lead to differences in the level and quality of public services ignited a national debate about the importance of equal access to educational opportunity. As the single largest source of local revenue, the property tax became the main target in this debate, giving rise to proposals that sought to reduce schools’ reliance on local property taxes and increase the state share of education spending to mitigate educational disparities. Between 1976 and 1981, the local property tax share of national education revenues declined from approximately 40 percent to 35 percent (McGuire, Papke, and Reschovsky 2015). But in the three decades since, the role of the local property tax in school funding has remained remarkably stable, never deviating much from that 35 percent.

In recent years, increased public concern about rising inequality has amplified the debate about ensuring equal access to educational opportunities and adequate funding to address the needs of all students, especially those in traditionally disadvantaged groups. Some suggest that an increase in state aid would accomplish this goal, but there are conflicting results in the literature as to whether centralizing school funding by substituting state aid for local property tax increases or decreases per-pupil spending and equity. With the pandemic forcing a reconsideration of school funding formulas, including those based on enrollment (see sidebar), the following excerpted case studies of Michigan, California, and Massachusetts offer examples that may be helpful to places considering the best way to provide an adequate and equitable education for all. Massachusetts relies heavily on the property tax to fund schools, while California and Michigan rely heavily on state aid (see table 1).

SCHOOL ENROLLMENT AND FUNDING FORMULAS

When the pandemic thrust students across the country into remote and hybrid learning, many public schools lost enrollment. For the 2020–2021 school year, enrollment was down 3 percent nationwide compared to 2019–2020. Declines were uneven across states and student groups, with the largest drops among pre-K and kindergarten students and among low-income students and students of color (NCES 2021). Since state aid for public schools is linked to the number of students attending or enrolled, a slump in attendance or enrollment can reduce that revenue. In response to these enrollment declines, many states adopted short-term policies to hold school districts harmless. Delaware and Minnesota, for example, provided extra state funding for declining districts. Many states, including New Hampshire and California, used prepandemic enrollment to calculate state aid (Dewitt 2021; Fensterwald 2021). Texas announced hold-harmless funding to districts that lost attendance if they maintained or increased in-person enrollment, in an effort to bolster in-person learning. All of these provisions are temporary, and states are waiting to see if enrollment will recover in 2022–2023. If it doesn’t, the data suggest that reduced funding for schools with the highest enrollment declines will disproportionately affect Black and low-income households (Musaddiq et al. 2021). These fiscal and equity concerns are causing educators to rethink the measurement of attendance and enrollment, and its link to funding.

Michigan: A Tax Swap

Michigan voters passed a proposal in 1994 that reduced reliance on the local property tax, shifting much of the state’s school funding to the sales tax and other taxes while restructuring state aid to schools. Research suggests this shift led to increased spending in the short term that improved some educational outcomes, but also resulted in a distribution of funds that did not reach the students who most need support.

Michigan voters had considered and defeated a series of proposals to restructure property taxes and school funding before approving Proposal A in 1994, which reduced reliance on the property tax and raised the sales tax to pay for that property tax relief. This “tax swap” greatly increased state education aid in the year of implementation and for some years after, changed the basic state aid formula, and changed the way state education aid is targeted.

The state raised the sales tax from 4 to 6 percent, depositing the revenue into the School Aid Fund. It obtained additional revenue from the income tax, real estate transfer tax, tobacco taxes, liquor taxes, the lottery, and a new state government property tax known as the State Education Tax. Local property taxes levied for school operating costs, which had averaged a rate of 3.4 percent before Proposal A, were eliminated; the state mandated a 1.8 percent local property tax rate on nonhomestead property, and all property became subject to the 0.6 percent State Education Property Tax.

State aid under Proposal A explicitly targeted low-spending districts. Increases in state funding were phased in over time, with substantial increases for low-spending districts, without reducing the funding of initially high-spending districts. In addition, school districts were allowed only limited options for supplementing education spending (Courant and Loeb 1997).

Because Michigan’s tax swap was enacted so long ago, we can observe the impacts of three recessions on state aid and local property tax funding. During the 1990–1991 and 2000–2001 recessions, reliance on state aid decreased while reliance on the local property tax increased. In the Great Recession, reliance on state aid decreased and reliance on the local property tax decreased slightly. The fact that the property tax was less effective as a backstop in the Great Recession is likely due to uniquely restrictive property tax limits in the state.

Michigan’s property tax is subject to all three main types of property tax limits: rate, levy, and assessment. In addition, one provision of the levy limit is particularly restrictive: not only does it require reductions in tax rates when the property tax base grows rapidly (“Headlee rollbacks”), but unlike most state levy limits, it prohibits increased tax rates without an override vote when the property tax base grows slowly or declines. This had a very constraining effect on property tax revenues during the Great Recession, when property values declined (Lincoln Institute 2020).

Although real per-pupil education revenue increased at a faster rate just after passage of Proposal A, beginning with the recession of 2000–2001, real state aid declined for many years, leading to slower growth or declines in total real per-pupil revenue and in educational expenditures per pupil (see figure 2). An empirical study to analyze the impacts of Proposal A on revenue and spending in K–12 education concludes that “the reform increases the level of school revenue and spending at the state level only in the first two years of the reform; the reform eventually decreases it two years after and onwards” (Choi 2017, 4).

Importantly, a tax swap may not create a more equitable school finance system. The school finance restructuring in Proposal A did reduce the disparities in school spending per pupil among school districts (Wassmer and Fisher 1996). This equalization was primarily accomplished by using state aid to raise per-pupil spending of the lowest-spending districts and placing some restrictions on spending on the highest-spending districts. But Michigan’s Proposal A was not designed to target aid to the children or the school districts most in need. It targeted additional school aid to previously low-spending school districts, which tended to be middle-income and rural.

An evaluation of the equity and adequacy of school funding systems across the United States concluded that resources in Michigan’s highest poverty districts are severely inadequate (Baker et al. 2021). Thirty-seven percent of students attend districts with spending below the amount required to achieve U.S. average test scores.

The recovery from the COVID recession, along with the massive influx of federal funds for education, may yet enable a turnaround in Michigan’s K–12 education system. In her 2022 State of the State address, Governor Gretchen Whitmer said her next budget would include the largest state education funding increase in more than 20 years (Egan 2022).

California: Shifting Control

California’s school finance narrative illustrates the tension between school funding equity goals and property tax reduction goals, providing a cautionary tale of the danger of diminishing local funding and the unintended consequences of assessment limits. In its pursuit of educational equity, California shifted funding away from local governments at the cost of local control. In taxpayers’ quest to control property tax increases, they traded horizontal equity for predictability.

Prior to 1979, California school districts raised over half of their revenue locally and school districts exercised control over their budgets and property tax rates. School finance litigation that began in the early 1970s drove legislation that began to erode this local control, shifting authority for property tax revenue distribution to the state in an attempt to equalize school district revenues. This series of cases, known as Serrano v. Priest, was motivated by concerns that the disparities in wealth among school districts created by dependence on local property taxes discriminated against the poor and violated California’s equal protection clause.

During the same period, dramatic growth in property tax values without an offsetting decrease in property tax rates incited a tax revolt that culminated in the passage of Proposition 13 in 1978. This citizen-initiated constitutional amendment fundamentally changed the nature of property tax assessments and imposed strict limits on growth in assessed values and property tax rates. Among other things, Proposition 13 limited growth in assessed values to 2 percent per year and capped cumulative property tax rates at 1 percent of assessed value.

Combined with the assessment limit, the rate limit provided certainty to taxpayers about how much property taxes could increase in the future—but stripped local governments and school districts of their ability to control spending levels and budgets.

Proposition 13 also instituted acquisition value assessment, under which properties are reassessed only when sold. This provides a strong incentive for taxpayers to remain in their homes and contributes to the state’s housing affordability crisis. Proposition 13 also prevented local governments and school districts from exceeding the limits in order to raise funds for local priorities, except for voter-approved bond measures. It required a two-thirds majority vote by both houses of the California legislature to increase any state tax and required a two-thirds majority vote of the electorate for local governments to impose special taxes.

In 1978, school district tax collections accounted for 50 percent of school district revenue; in 1979, they made up only a quarter of total revenue. The state aid share of school district revenue, supported mostly by state income taxes, climbed from 36 percent in 1978 to 58 percent in 1979.

In 1986, the California Court of Appeal held that the state’s centralized school finance system complied with the state constitution. The court found 93 percent of California students were in districts with wealth-related spending differences of less than $100 per pupil as prescribed by the courts in 1976. While the reforms satisfied the court, making per-pupil spending more consistent among school districts has not definitively improved or equalized educational outcomes.

Together, the court rulings and Proposition 13 altered the school finance landscape in California and inspired a wave of property tax revolts and school finance litigation across the United States. The school finance reforms in California successfully constrained revenues, but at the cost of local control and to the detriment of education quality. School districts lost control over their primary revenue source, per-pupil spending fell below the national average (see figure 2), and academic achievement and public school enrollment declined (Brunner and Sonstelie 2006; Downes and Schoeman 1998).

California’s test scores continue to suffer. National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores for California show that its students continue to perform below the national average, although the gaps have narrowed since 2013, when California enacted the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) school finance reforms (see figure 3). Among other reforms, the LCFF targets aid to high-need districts through concentration grants and gives districts more discretion over how they spend state funds.

One analysis suggests that California’s reforms played a major role in the rapid decline in public school enrollment in the 1970s and a partial role in the rapid growth in private school enrollment during the same period (Downes and Schoeman 1998).

Persistent efforts to amend the state constitution to eliminate acquisition value assessment for nonresidential property provide evidence of long-term dissatisfaction with Proposition 13 among some Californians. Referred to as a “split roll,” such proposals are often debated but rarely make it to the ballot. Voters narrowly defeated one such proposal, Proposition 15, in November 2020. Proposition 15 would have returned certain commercial and industrial real property to market-value assessment while preserving acquisition value assessment for residential properties and most small businesses.

Massachusetts: Targeted Aid

Massachusetts’ case indicates that targeting state aid to the school districts that need it most and linking accountability standards to increased school aid can produce strong academic results. The state was also able to reduce reliance on the property tax while improving its property tax system. However, recent years show that even strong school finance systems can backtrack and should be reevaluated periodically.

In 1980, Massachusetts enacted a property tax limit known as Proposition 2½. The two most important components of Proposition 2½ limit the level and growth of property taxes: they may not exceed 2.5 percent of the value of all assessed value in a municipality, and tax revenues may not increase more than 2.5 percent per year. Because K–12 schools are part of city and town governments in the state and not independent governments, as in some states, Proposition 2½ directly affects schools.

One might expect that reducing reliance on the property tax in a state that does not allow local governments to levy either sales or income taxes might heavily constrain local government revenues. But local governments were lucky in the timing of the enactment of Proposition 2½. The tax limitation came into force at the beginning of a period of significant economic growth in the state popularly termed the “Massachusetts Miracle.” This enabled the state to increase aid to localities, which cushioned the tax limitation’s impact.

Also important is the fact that Proposition 2½ was not a constitutional amendment, but a piece of legislation that could be modified by the legislature—and was. Altogether, Proposition 2½ had “a smaller impact than either its supporters had hoped or its detractors had feared” (Cutler, Elmendorf, and Zeckhauser 1997). Although not perfect, Proposition 2½ is less restrictive and less distortionary than many property tax limits in other states (Wen et al. 2018).

During the 1980s, the state also reformed its property tax system by moving to assessing properties at full market value. Before this reform, most properties, especially residential ones, were assessed at far less than market value, with high-income properties receiving preferential treatment. Proposition 2½ created an incentive to move to the full value because of the 2.5 percent cap on the property tax levy.

As the state was coming out of a deep recession in the early 1990s, the quality of its public schools had caused broad dissatisfaction. The Massachusetts Business Alliance for Education published Every Child a Winner in 1991, calling for “high standards, accountability for performance, and equitable distribution of resources among school districts” (MBAE 1991). The highest court was considering an equity lawsuit that had been filed in 1978, and the state Board of Education published a report highlighting some schools’ shortcomings (Chester 2014).

In 1993, a pivotal year, the state legislature passed the Massachusetts Education Reform Act (MERA) and the state’s highest court ruled in McDuffy that the state was not meeting its constitutional duty to provide an adequate education for all students. MERA had a number of important components, including a large increase in state aid for education (from $1.6 billion in 1993 to $4 billion in 2002), and a new school funding formula targeted to districts that needed it most. Another component of MERA was curriculum standards and accountability. In 1998, the MCAS (Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System) was administered for the first time to measure student achievement.

In a second school funding lawsuit, Hancock v. Driscoll, settled in 2005, the Supreme Judicial Court concluded that “a system mired in failure has given way to one that, although far from perfect, shows a steady trajectory of progress” (Costrell 2005, 23). One measure of Massachusetts’ achievement is the improvement of state scores on NAEP tests (see figure 3). Although the original intention was to reevaluate and, if need be, revise the state’s school funding formula periodically, that did not happen. Furthermore, after several years of growth in state school aid, cuts came in 2004, then again in 2009 after the onset of the Great Recession.

In 2015, a Foundation Budget Review Commission was established to review the state’s school aid system (Ouellette 2018). The commission concluded that local governments were bearing a disproportionate share of the cost of educating children and that several elements of the foundation aid program, such as the way health insurance costs were taken into account, were outdated.

In 2019, the legislature passed and Governor Charlie Baker signed the Student Opportunity Act (SOA), which provides $1.5 billion in additional school aid better targeted to low-income students. This revised school aid system was designed to be phased in over seven years. In 2020, the state delayed the funding increases because of pandemic-related economic uncertainty. However, in 2021, the legislature fully funded the act for the first time (Martin 2021).

Finding the Right Combination

Neither state aid nor the property tax on its own can provide adequate, stable, and equitable school funding. But the right combination can provide all three. Just as weaving requires lengthwise and crosswise threads (the warp and woof), so a sound school finance system requires a well-designed property tax and well-designed state school aid.

The system of state and local funding should provide sufficient funding so that all children, no matter their race, ethnicity, or income, can receive an adequate education. When designed properly, state aid can ensure that all school districts can provide an adequate education and weaken the link between per-pupil property tax wealth and per-pupil education funding—without sacrificing the benefits that come from a stable property tax base and local control of public schools.

Daphne Kenyon is a resident fellow in tax policy at the Lincoln Institute. Bethany Paquin is a senior research analyst at the Lincoln Institute. Semida Munteanu is associate director, valuation and land markets at the Lincoln Institute.

Lead image by skynesher via Getty Images.

REFERENCES

Baker, Bruce, Matthew Di Carlo, Kayla Reist, and Mark Weber. 2021. The Adequacy and Fairness of State School Finance Systems, School Year 2018–2019, Fourth Edition. Albert Shanker Institute and Rutgers University Graduate School of Education. December.

Brunner, Eric J., and Jon Sonstelie. 2006. “California’s School Finance Reform: An Experiment in Fiscal Federalism.” Economic Working Papers 200609. Hartford, CT: University of Connecticut.

Chester, Mitchell. 2014. Building on 20 Years of Massachusetts Education Reform. Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education.

Choi, Jinsub. 2017. “The Effect of School Finance Centralization on School Revenue and Spending: Evidence from a Reform in Michigan.” Proceedings, Annual Conference of the National Tax Association (110): 1–31.

Costrell, Robert M. 2005. “A Tale of Two Rankings: Equity v. Equity.” Education Next, Summer: 77–81.

Courant, Paul N., and Susanna Loeb. 1997. “Centralization of School Finance in Michigan.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 16 (1): 114–136.

Cutler, David M., Douglas W. Elmendorf, and Richard Zeckhauser. 1997. “Restraining the Leviathan: Property Tax Limitation in Massachusetts.” Working Paper 6196. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Dewitt, Ethan. 2021. “School Enrollment Decline Persists Despite Return to Classrooms.” New Hampshire Bulletin, November 24.

Downes, Thomas A., and David Schoeman. 1998. “School Finance Reform and Private School Enrollment: Evidence from California.” Journal of Urban Economics 43 (418–443).

Education Week. 2020. “The Coronavirus Spring: The Historic Closing of U.S. Schools (A Timeline).” July 1.

Egan, Paul. 2022. “Whitmer Budget to Propose Billions Extra for Schools, Five Percent Boost in Per-Pupil Grant.” Detroit Free Press. February 6.

Fensterwald, John. 2021. “Projected K–12 Drops in Enrollment Pose Immediate Upheaval and Decade-long Challenge.” EdSource, October 18.

Griffith, Michael. 2021. “An Unparalleled Investment in U.S. Public Education: Analysis of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.” Learning in the Time of COVID. Washington, DC: Learning Policy Institute.

Korman, Hailly T.N., Bonnie O’Keefe, and Matt Repka. 2020. “Missing in the Margins 2020: Estimating the Scale of the COVID-19 Attendance Crisis.” Bellwether Education, October 21.

Lincoln Institute. 2020. “Towards Fiscally Healthy Michigan Local Governments.” Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, October.

Martin, Naomi. 2021. “Low-Income Students Are Receiving ‘Game-Changer’ Student Opportunity Act Funding.” Boston Globe. July 17.

MBAE. 1991. “Every Child a Winner.” Boston, MA: Massachusetts Business Alliance for Education.

McGuire, Therese J., Leslie E. Papke, and Andrew Reschovsky. 2015. “Local Funding of Schools: The Property Tax and Its Alternatives.” In Handbook of Research in Education Finance and Policy, 392–407. New York, NY: Routledge.

Musaddiq, Tareena, Kevin Stange, Andrew Bacher-Hicks, and Joshua Goodman. 2021. “The Pandemic’s Effect on Demand for Public Schools, Homeschooling, and Private Schools.” Working paper 29262. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

NCES. 2021. “New Data Reveal Public School Enrollment Decreased 3 Percent in 2020–2021 School Year.” Blog post. National Center for Education Statistics. July 26.

Ouellette, John. 2018. “Two Decades into Education Reform Effort, Commission Calls for Substantial Changes to Funding Formula.” Municipal Advocate: 29 (2).

Sawchuk, Stephen. 2020. “When Schools Shut Down, We All Lose.” Education Week. March 20.

Wassmer, Robert W., and Ronald C. Fisher. 1996. “An Evaluation of the Recent Move to Centralize the Funding of Public Schools in Michigan.” Public Budgeting and Finance 16 (Fall): 90–112.

Wen, Christine, Yuanshuo Xu, Yunji Kim, and Mildred E. Warner. 2018. “Starving Counties, Squeezing Cities: Tax and Expenditure Limits in the U.S.” Journal of Economic Policy Reform 23(2): 101–119.

Perched at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, the city of Norfolk, Virginia, has long relied on its proximity to water as a source of economic strength, from its history as a key port in the 18th and 19th centuries to its current role as the site of the world’s largest naval station. Miles of beaches and a downtown riverfront trail draw tourists and residents alike. But the location of this low-lying coastal city makes it especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change, including sea-level rise, flooding, and increasingly powerful and frequent coastal storms.

To address these risks, leaders in Norfolk have put climate adaptation at the center of their long-term planning. In 2018, the city revised its zoning to codify resilience standards and nudge new development toward higher ground. A new study by Smart Growth America (SGA) will examine the economic impacts of that zoning change, including its effects on the municipal budget and projected effects on property values. The research—which will be led by Katharine Burgess, vice president of land use and development, and supported by the Lincoln Institute—will also include a national scan to identify and categorize other resilience zoning initiatives and develop a list of complementary policy approaches, addressing topics such as anti-displacement, housing affordability, and environmental justice. The team hopes those findings will serve as a resource for policy makers in cities across the United States.

The study by SGA is one of seven projects the Lincoln Institute is supporting through a call for research on the intersection of land-based climate change adaptation, property values, and municipal finance. Over the next year, each project will explore the fiscal impacts that various climate adaptation approaches—such as green infrastructure, floodplain buyouts, and rezoning—have on the places that implement such approaches.

“The findings of these research projects will illuminate fiscal dimensions of land-based adaptation measures and help communities identify more effective and equitable strategies to advance their climate goals,” said Amy Cotter, director of climate strategies at the Lincoln Institute. “We hope this research will help inform and change public policy, and ultimately change practice.”

In addition to SGA’s study of resilience zoning in Norfolk, the following projects will receive support from the Lincoln Institute:

To learn more about current Lincoln Institute requests for proposals, fellowships, and other research opportunities, visit our research page.

Katharine Wroth is the editor of Land Lines.

Image: Low-lying Norfolk, Virginia, is taking steps to build climate resilience. Credit: Jupiterimages via Stockbyte/Getty Images.

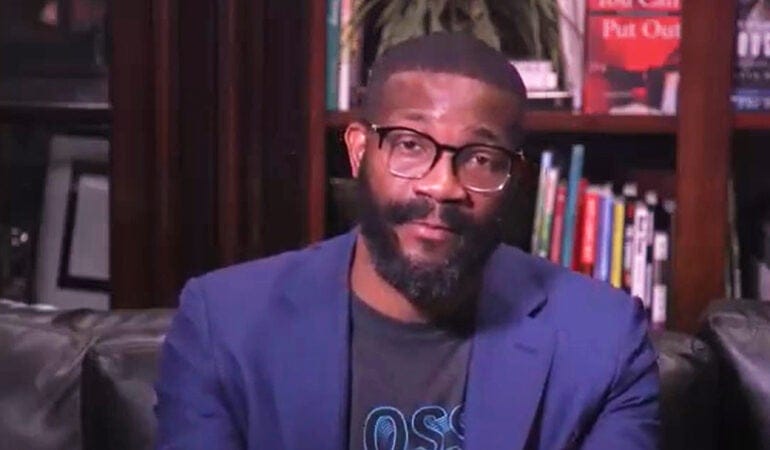

Randall Woodfin, Birmingham’s “millennial mayor” and rising star in Alabama politics, has launched an urban mechanic’s agenda for revitalizing that post-industrial city: restoring basic infrastructure on a block-by-block basis, setting up a command center so federal funds are spent wisely, and providing guaranteed income for single mothers.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to really supercharge infrastructure upgrades and investments we need to make in our city,” Woodfin said, referring to the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the American Rescue Plan Act, which are bringing unparalleled amounts of funding to state and local governments. “This type of money probably hasn’t been on the ground since the New Deal.”

Woodfin talked about neighborhood revitalization, housing, climate change and other topics in an interview for the Land Matters podcast. An edited version of the Q&A will appear in print and online as the Mayor’s Desk feature in the next issue of Land Lines magazine.

When he was elected in 2017, Woodfin was the youngest mayor of Birmingham in over a century. Now 40 and nearly a year into his second term, he’s made revitalization of the city’s 99 neighborhoods a top priority, along with enhancing education, fostering a climate of economic opportunity, and leveraging public-private partnerships.

In a city battered by population and manufacturing loss — including iron and steel industries that once thrived there — Woodfin looked to education and youth as keys to a better future. He set up Birmingham Promise, which provides apprenticeships and college tuition assistance to local high school graduates. He also established Pardons for Progress, a mayoral pardon of 15,000 misdemeanor marijuana possession charges dating back to 1990, that had been a barrier to employment.

Woodfin is a graduate of Morehouse College and Samford University’s Cumberland School of Law. He was an assistant city attorney for eight years before running for mayor, and served as president of the Birmingham Board of Education as well.

Too many Birmingham residents have been living in areas where they are constantly reminded of decline, Woodfin said — stepping out of their house and seeing a dilapidated house next door and a broken streetlight out front. Playground and park equipment is out of order, and many live in food deserts. The answer, he said, is to “triple down” on efforts to create new housing and other infrastructure and eradicate blight, to address “snaggletooth” blocks where “you have a house, empty lot, house, empty lot, empty lot.”

Chipping away at concentrated poverty through physical improvements improves quality of life for thousands, and will help the entire city rebound, Woodfin says.

More near-term, Woodfin said he embraced the concept of guaranteed income because as a practical matter, a few hundred dollars a month could help single mothers fend off “the monotony of concentrated poverty.”

“I think we all would agree, no one can live off $375 a month,” he said. But if households had that additional money, “does that help keep food on the table? Does it help keep your utilities paid? Does it help keep clothing on your children’s back and shoes on their feet? Does it help you get from point A to B to keep your job to provide for your child?

“This is why I believe this guaranteed income pilot program will be helpful. We only have 120 slots, so it’s not necessarily the largest amount of people, but I can tell you over 7,000 households applied for this,” he said. “The need is there.”

The Lincoln Institute’s Legacy Cities Initiative is developing a community of practice for the equitable regeneration of post-industrial cities, like Birmingham, that have been hit hard by manufacturing and population loss. Strategies to maintain good municipal fiscal health for these and all cities include one that Woodfin is making a priority: keeping better track of intergovernmental transfers, such as the billions in federal funding that is currently on the way.

You can listen to the show and subscribe to Land Matters on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Anthony Flint is a senior fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, host of the Land Matters podcast, and a contributing editor of Land Lines.

Photograph courtesy of Anthony Flint.

Further reading:

Everything you need to know about Birmingham’s millennial mayor

Seven Strategies for Equitable Development in Smaller Legacy Cities

How Smarter State Policy Can Revitalize America’s Cities

The Empty House Next Door: Understanding and Reducing Vacancy and Hypervacancy in the United States

American cities need to pursue creative new strategies as they rebuild from the COVID-19 pandemic and work to address longstanding social and economic inequities. Too often, however, cities face stiff headwinds in the form of state laws and policies that hinder their efforts to build healthy neighborhoods, provide high-quality public services, and foster vibrant economies in which all residents have an opportunity to thrive, according to a new Policy Focus Report by Center for Community Progress Senior Fellow Alan Mallach from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and the Center for Community Progress.

With a massive infusion of funds from the American Rescue Plan into cities and states, advocates for urban revitalization have an unprecedented opportunity to engage with state policy makers in creating a more prosperous, equitable future, Mallach writes in the report, From State Capitols to City Halls: Smarter State Policies for Stronger Cities. “If there’s one central message in this report, it’s that states matter—and that those who care about the future of our cities need to direct far greater attention to them,” he writes.

Based on a detailed analysis of the complex yet critical relationship between states and their cities, the report illustrates how state policies and practices affect the course of urban revitalization, from the ways cities raise revenues to the conditions under which they can finance redevelopment. The report provides a rich picture of how state laws and practices can help or hinder equitable urban revitalization, drawing upon examples and strategies from across the country and highlighting the recurrent city–state tug-of-war that both must move beyond to work together for mutual benefit.

The report also breaks down what goes into successful revitalization, and how leaders can use legal and policy tools to bring about more equitable outcomes. Mallach recommends five underlying principles that should ground state policy related to urban revitalization: target areas of greatest need, think regionally, break down silos, support cities’ own efforts, and build in equity and inclusivity.

“This report is thorough, relevant, and timely—and it provides a critical perspective on the importance of building capacity to ensure stronger alignment between state and local policy makers to improve equity and inclusion,” said Sue Pechilio Polis, the director of health and wellness for the National League of Cities. “A detailed accounting of all of the ways state laws impact municipalities, this essential report will be a must read for state and local policy makers.”

“As this Policy Focus Report details, state governments must be true partners with their cities in order to realize meaningful, equitable revitalization across the board,” said Jessie Grogan, associate director of reduced poverty and spatial inequality at the Lincoln Institute. “By deliberately incorporating equity into economic growth and community work across locations and sectors, leaders at every level can foster truly progressive change.”

From State Capitols to City Halls offers specific state policy directions to help local governments build fiscal and service delivery capacity, foster a robust housing market, stimulate a competitive economy, cultivate healthy neighborhoods and quality of life, and build human capital, all with the goal of bringing about a more sustainable, inclusive revival in American cities and towns. The report’s recommendations offer a practical roadmap to help state policy makers take a fresh look at their own laws and further more effective advocacy for substantive change by local officials and non-governmental actors.

“We all deserve access to stable jobs, affordable housing, and green spaces, but unfortunately our systems aren’t built to guarantee that for future and even current generations,” said Massachusetts State Senator Eric P. Lesser, who chairs the Gateway Cities Caucus and the Economic Development Committee. “This report takes a thoughtful look at how we as policy makers can have a direct impact on building inclusive cities for all. From State Capitols to City Halls: Smarter State Policies for Stronger Cities provides real tools to support our communities, break down policies that breed inequality, and give everyone a fair shot at a high quality of life.”

While successful strategies will vary from state to state, Mallach stresses that all policy makers must remember that every state is fundamental to its cities’ futures as places of equity and inclusion. “In the final analysis,” he notes, “states play a central, even essential, role in making revitalization possible—or, conversely, frustrating local revitalization efforts. This report should encourage public officials and advocates for change to make states more supportive, engaged partners with local governments and other stakeholders in their efforts to make our cities stronger, healthier places for all.”

The report is available for download on the Lincoln Institute’s website: https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/policy-focus-reports/state-capitols-city-halls

Image: USA/Alamy Stock Photo

From the suburban boomtowns of the Colorado River Basin to the postindustrial cities of the Northeast, communities across the United States can benefit from integrating land and water planning in the face of increasing water demands, climate change, and other risks, according to a new Policy Focus Report from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

In Integrating Land Use and Water Management: Planning and Practice, author Erin Rugland of the Lincoln Institute’s Babbitt Center for Land and Water Policy explains how integrating land and water can help communities deal with increased drought or flooding as they navigate the uncertainty of a warming planet and changes in their communities. She outlines best practices in land use planning and water management, provides a detailed menu of policy tools, and shares four success stories from vastly different places: Evans, Colorado; Hillsborough County, Florida; Philadelphia; and Golden Valley, Minnesota.

“Water is not only essential to life and to thriving communities, but it brings value to land,” Rugland writes in the report. “Land use determines the character of communities and in turn greatly impacts water demand, water quality, and flooding risks. Connecting land with water and understanding these resources in the context of issues like equity, resiliency, and climate change is critical for building and sustaining healthy communities for the future.”

Although land and water are inextricably linked, land use planning and water management have historically occurred in silos. Rugland clearly explains each discipline, focusing on a key policy framework for each—the comprehensive plan and the water management plan. Comprehensive plans lay out a community’s long-term vision, with an emphasis on themes like economic development, transportation, and housing. Water management plans vary more widely from place to place; some focus narrowly on drinking water supply, while others incorporate wastewater and stormwater.

As the report describes, state policy can play a significant role in promoting the integration of land and water planning, whether through mandates or resources. Colorado, for instance, requires utilities to consider how land use efforts can reduce water use. The state also supports the Colorado Water and Land Use Planning Alliance, a peer learning group for local practitioners. Pennsylvania is one of five states to require a water element in local comprehensive plans. And Minnesota’s state legislature established the Metropolitan Council, one of the strongest regional planning agencies in the country, which helps communities in the Twin Cities area coordinate development plans with water supplies and requirements.

The report shows how four communities, driven by state policy and their own initiative, have integrated land and water planning in different ways:

The report offers four key recommendations for policy makers based on the experiences of these communities and others: collaborate locally, coordinate regional expertise and oversight, build capacity through funding and technical assistance, and use state mandates.

“Integrating Land Use and Water Management is relevant, informative, and necessary at this moment in time,” said Chi Ho Sham, president of the American Water Works Association and vice president and chief scientist of Eastern Research Group. “In the age of specialization, we have created many silos. As problems with the urban water cycle become more complex and multidimensional, collaboration with other disciplinary experts is needed. This report provides a practical bridge to facilitate collaboration between land use planners and water management.”

Image: Master-planned community in Chandler, Arizona. Credit: Art Wager via Getty Images.

At Capital City Farm, the first commercial urban farm in Trenton, New Jersey, more than 37 varieties of fruits, vegetables, and flowers grow on two formerly abandoned city-owned acres. The farm, run by the D&R Greenway Land Trust, is a financially self-sufficient operation that donates 30 percent of its produce to the Trenton Area Soup Kitchen and sells the rest to nearby markets. A local community development and environmental nonprofit runs a well-established youth gardening program at the farm, which has won several awards since its founding in 2016.

There’s no question that Capital City Farm is a success story on many levels, from repurposing a trash-strewn lot to involving the local community in its development and operations. Now the city is hoping to emulate that success, working closely with local residents as it sets out to convert additional vacant lots into community gardens. The effort is part of a recently launched plan called Fight the Blight, which will include property demolition and redevelopment.

Trenton, population 83,000, has a disproportionate number of neglected and vacant properties: 1,500 of them in a city that covers just 7.5 square miles. As the city embarks on addressing this issue, officials are sensitive to the fact that, for residents in neglected urban neighborhoods, municipal improvement efforts can be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, fixing up vacant lots and tearing down condemned buildings yields major quality of life improvements, including improving public safety and increasing community morale. But on the other hand, the sudden arrival of plans and projects developed without local input can be an unwelcome signal to residents that the future of the neighborhood is out of their hands and might not include them.

“Trenton . . . has historically been behind the eight ball” on securing local input in revitalization efforts, said the city’s principal planner, Stephani Register. “The way we’re approaching it now is this idea of ‘let’s give the people back their power.’ If we do that, we as an administration get better participation from residents. The question is, how do you do that for communities of color who have been disenfranchised for so long because they didn’t have the right information, and the tools that are out there have been used against them.”

An interdisciplinary team from Trenton is exploring these issues through its participation in the Lincoln Institute’s Legacy Cities Communities of Practice project. Over the past year, teams from three legacy cities (Trenton; Akron, Ohio; and Dearborn, Mich.) have met regularly to facilitate peer learning, gain insights from expert faculty on issues ranging from racial equity to fiscal health, and access resources and support to tackle entrenched citywide policy issues with place-based project approaches. Trenton’s team includes Register, mayoral aide Rick Kavin, Jamilah Harris, an analyst from the state Department of Environmental Protection, and Caitlin Fair, executive director of the nonprofit East Trenton Collaborative (ETC).

Legacy cities like Trenton are places that have experienced population and economic decline that has left them with common infrastructure and demographic challenges. Many of them have vast areas once full of people and industry that have now been abandoned and neglected. Smaller legacy cities have many of the same challenges as larger legacy cities like Detroit or Baltimore, said Jessie Grogan, associate director of Reduced Poverty and Spatial Inequality at the Lincoln Institute. But they tend not to draw the same national attention from think tanks or large philanthropic funders, and they tend to have smaller municipal staffs and budgets.

“These cities are kind of left to solve really complex problems on their own,” she said. “These smaller cities are in a tough spot where they have enough capacity to know what the problems are, but not enough to know what the potential solutions are or what their peer cities are doing that’s working.” The Legacy Cities Community of Practice gives them an opportunity to compare notes, get new ideas, and support each other’s work.

Trenton, for example, is now working to engage the community in its Fight the Blight program using strategies employed in Syracuse, N.Y., and Flint, Mich., and detailed in the Lincoln Institute’s Policy Focus Report Revitalizing America’s Smaller Legacy Cities. Rather than the city taking the lead in projects like the effort to expand its community gardens, officials have turned to community organizations. Kavin said Capital City Farm has been advising the city on the youth apprenticeship aspect of the proposed community garden project. And Fair says the ETC would like to see community gardens become year-round, accessible neighborhood resources that support workforce development and a healthy community.

“The idea is to marry [the gardens] with our youth employment program and for the city to create an opportunity for kids in the community to have a paid apprenticeship,” she said. “A goal of this initiative is to create a very public, community-oriented space that is open to everyone to use.”

The vision is for Trenton’s new community gardens to be financially self-sustaining, providing a steady source of local jobs and local food thanks to greenhouses and hydroponic gardening that make cultivation possible during the winter months. Allowing year-round structures such as greenhouses on lots operated as community gardens required a zoning code change, which the Trenton team collaborated on and achieved by mid-2021. In the fall of 2021, the ETC began working on deciding which vacant lots in East Trenton they want to turn into community farms.

Ultimately, the Trenton team sees the community farm project as just one way to start breaking down barriers between local government and residents and approach planning from a more holistic perspective. To that end, the city has also launched “how-to” informational sessions aimed at increasing small business owners’ access to capital and city contracts. Other sessions help homeowners figure out how to access grant money or loans to fix up their historic homes. And last year, Trenton launched an “Adopt a Lot” program that gives residents temporary access to vacant lots for their own gardens or other greenspace use.

“With all of these programs, we’re trying to foster an environment where all local residents can have a say,” Kavin said. “Not just in their city’s planning, but also in their own future.”

Liz Farmer is a fiscal policy expert and journalist whose areas of expertise include budgets, fiscal distress, and tax policy. She is currently a research fellow at the Rockefeller Institute’s Future of Labor Research Center.

Image: Volunteers plant seeds at Capital City Farm in Trenton, New Jersey. Credit: Capital City Farm.