Amid the jagged peaks of the San Juan Mountains, in the northeast quadrant of the Four Corners regional border, is a cluster of five southwestern Colorado counties whose names evoke the region’s rich and diverse history: Montezuma, San Juan, La Plata, Dolores, Archuleta.

Diverse, too, is the way of life and the economy of the region—from tourism and agriculture to fossil fuel extraction. Fewer than 100,000 people populate the varied and mountainous area. The cities of Durango and Cortez represent a bit of relatively bustling semi-urban life, while small mountain towns and two Native American reservations occupy outposts across the 6,500-square-mile area, roughly the size of Connecticut.

For these far-flung communities, planning for the future has become much more uncertain in the 21st century, as the wildcard of climate change and the vagaries of the energy industry have minimized sure bets. Educated guesses about the coming decades are getting harder to make across many dimensions: from unpredictable prices and revenues within the natural gas industry to swings in the size of the snowpack, affecting river flow, crops, and skiing alike. And many variables are highly interconnected.

“Our biggest question is our vulnerability to drought,” says Dick White, city councilor in Durango. “Our agricultural and tourism industry could be totally disrupted if we go into long-term drought and have lots of wildfires.”

Recognizing the need for wider policy coordination, a regional group of governing bodies formed the Southwest Colorado Council of Governments in late 2009, to address larger challenges and to seek out collaborative opportunities. Yet, in terms of policy, the road-map to stability, sustainability, and economic prosperity has not necessarily become clearer.

The conundrums at hand may simply surpass the conventional planning tools themselves, observers say. Regional planning as a discipline, of course, stretches back decades, but the procedures, templates, and models employed—from “visioning” to “normative,” “predictive,” or “trendline” methods—are not always up to the task of grappling with irreducible uncertainties. So, last year, the Southwest Colorado Council embarked on an intensive process in partnership with Western Lands and Communities—a joint program of the Sonoran Institute and the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy—with an emerging policy tool that embraces the very idea of uncertainty: exploratory scenario planning, or XSP. Unlike the normative or traditional planning processes, it is not about what is preferred—an expression of community values—it is about what may happen beyond the control of planners involved.

XSP requires participants to identify the greatest causes of uncertainty in their community and use those challenges to envision alternative scenarios of the future. Whereas two to four scenarios would typically result from more traditional forms of scenario planning, the Southwest Colorado Council created eight scenarios during their XSP sessions.

Early in 2015, consultants, experts, and regional policy makers converged in the city of Durango to unpack a crucial question that would generate relevant scenarios: “Given the possibility of extended long-term drought and its potential environmental impacts, how could the Five-County Region develop a more adaptable economy?”

The question—which the group worked out through a careful, community-oriented process—became the focus of an extensive process of fact-gathering and analysis. This research culminated in two workshops structured to explore a variety of regional “futures”—the possible and plausible ways in which life in southwest Colorado could play out. The time horizon was to be 25 years, through 2040.

Participants considered the interrelated impacts of several critical areas of uncertainty, including the length of potential drought, local production levels of natural gas, and the cost of oil.

The central idea behind XSP is to bring together stakeholders to advance a multistep planning process that imagines many futures and formulates strategic insights accordingly. Its methodological steps are roughly: first, formulate a core set of questions; then, precisely identify and rank the forces of change; next, create narratives around possible scenarios and their implications; and, finally, formulate active responses and discern actions that would help address multiple scenarios. The process, says Miriam Gillow-Wiles, executive director of the Southwest Colorado Council of Governments, furnished a fresh way to help planners and policy makers imagine regional dynamics. “I think it set the council of governments up to be not just another economic development organization or government organization, because we are doing something different,” she says.

The project was also another step by Sonoran and Lincoln toward fine-tuning the concept and ultimately testing the value of exploratory scenario planning—which has its early roots in the business management and military spheres—in the context of urban and regional planning. Other recent case studies have been explored in central Arizona, in the Upper Verde River Watershed and the Town of Sahuarita, just south of Tucson, Arizona.

“This is something that is not only a good idea intellectually,” says Peter Pollock, manager of Western Programs at the Lincoln Institute. “It will add real value to your community planning process to deal with real problems.”

A Range of Futures

Dealing with real—and really tough—problems is the name of the game in southwest Colorado, as the region faces a “daunting” array of changes all at once, according to a 2015 report, “Driving Forces of Change in the Intermountain West,” prepared as part of the exploratory scenario planning process. Some are demographic—inflow of population, with more Hispanics, coupled with urbanization. Others relate to the “uncertain and complex” nature of the energy industries, which are affected by volatile global economic patterns.

Durango City Councilor White says he and fellow policy makers have been forced to think a lot about these shifts as their city considers a variety of infrastructure projects, from expanding the sewer treatment system to growing the size of the airport. White, a former Smith College astronomy professor who retired early and moved West to get involved in environmental policy, was a key member of the group that met last year in Durango as part of the Southwest Colorado Council of Governments.

“You’ve got this range of possible futures, and you really don’t know which road you’re going to go down,” he says. “The idea is to identify the biggest risks and best ‘no regrets’ policies.”

For White, the entire exercise of gaming out how varying drought conditions might affect the whole regional economy helped clarify issues. “Conceptually, I find that an extraordinarily useful policy tool,” he says. The sewer and airport infrastructure questions have subsequently been cast in a new light: “I have seen both of these decisions through the lens of [exploratory] scenario planning.” Given future uncertainties, White says he is determined to make investments that will give future policy makers flexibility should they need to make further infrastructure changes.

The final “low-regret” actions and strategies that stakeholders identified included: better coordination with federal agencies on forest management, public-private partnerships to promote use of biomass and biofuel, assessments of available land for development, identifying new opportunities to augment water resources from groundwater, the charging of real costs for water service and realistic impact fees, and support for small business and agriculture incubators.

Those insights and associated new perspectives are often hard-won, planners and participants concede. Exploratory scenario planning, as the southwest Colorado project demonstrated, can be a demanding process.

Hannah Oliver, who co-facilitated the scenario planning effort as a program manager with the Sonoran Institute in the Western Lands and Communities program, recalls driving all over the southwest Colorado region to get a feel for its land and its people and conducting many interviews with stakeholders. And that was just to prepare the groundwork—the “issues assessment”—for the stakeholder meetings.

The goal of the workshops themselves is to push the boundaries of the possible while staying within the bounds of the realistic. “You don’t want the scenarios to be so outlandish that community members can’t see themselves in it,” she says. The process aims to generate what Oliver, who was joined as a facilitator by Ralph Marra of Southwest Water Resources Consulting, calls “Ah-hah” moments. In this case, participants came to understand the profound implications of lower gas production, severe drought, and swings in oil prices—with ripple effects across the tourism and agriculture industries and with deep overall impacts on the regional economy. Southwest Colorado, they realized, could face a very different future under certain plausible conditions.

“You come out exhausted,” Oliver says of the typical initial workshop. “For the participants, it’s like going to a boot camp. People coming out of that workshop say, ‘I’ve never had to think like that before.’”

For community members, it can certainly take a lot of concentration to juggle the variables. “I think the whole way of scenario planning—if X, then Y—is a really useful way to look at things,” says Gillow-Wiles. But “the whole process itself can be challenging, because there are so many unknowns.”

Lessons Learned

A key to success, in any case, is to gather a broad range of people into the same room. In a wide and geographically dispersed region, that can be challenging. “Having a diversity of opinions is really important,” says Oliver, who is now a village planner in Phoenix. “Because the stuff you get out of the workshops is only as good as what goes in.”

Some southwest Colorado participants suggest that framing the exercise more directly around economic development or a more specific infrastructure issue (opposed to drought) might have attracted more participation from policy makers. “It’s sometimes hard to get your board members to buy into that kind of pie-in-the-sky type of thing,” says Willow-Giles, “versus something more tangible like ‘What do we do with our population growth in terms of transportation 25 years from now?’”

Likewise, White cautions that the ability to create momentum and community energy is not a given. “If I had a lesson to draw,” he notes, it’s that “you have to really work hard to make sure that you continue to have appropriately diverse representatives at both ends of the process.”

The southwest Colorado region has its share of political hot-button issues—including the politics of climate change and the dynamics of the fossil fuel companies there—but participants report that they steered clear of the land mines during the XSP process. (Drought, many note, has long afflicted the region, even prior to the Industrial Revolution; indeed, the ancient Puebloans likely left their famed cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde because of dry conditions.)

Pollock says that one of the virtues of XSP is that it allows in and even encourages conflicting views that can make it more inclusive, both in terms of process and outcomes. It minimizes arguments about which future is “right,” and it helps build support for action among the diverse group that has come together to develop the strategies. “We think it is a way to defuse some of the political questions that make our public process overly rancorous and difficult,” he says.

By bringing diverse ideas into the process early and openly embracing uncertainty, exploratory scenario planning can yield fewer surprises in the end for a community, according to Uri Avin, research professor and director of the Center for Planning and Design at the National Center for Smart Growth, University of Maryland. “The opponents of your end-state vision may, at the end of your visioning plan, come out of the woodwork and fight you,” he says. “Whereas exploratory scenarios explicitly tend to invite dissention and debate, and the construction of scenarios that embrace other viewpoints.”

One of the stark truths that can emerge from such a candid process is the reality that negative change may be likely under very plausible future conditions. Oliver says that participants in fact came to the realization that certain linear assumptions about the region’s economic future may need to be scrutinized.

“I think what struck them is the understanding that the oil and gas industry may not be around forever,” says Oliver. One of the biggest things they realized was how much they relied on money from natural gas production for basic services, she says. “They realized they might not be able to offer as many services if oil and gas were gone.”

Avin says that XSP operates as a kind of antidote to the traditional notion of plans-as-silver bullets. But, politically, that realism can be a challenging sell. “It may include accepting decline or change that may not be palatable but may be inevitable if certain things happen,” he says. “So the initial hurdle for planners is getting their arms around it and persuading their bosses who are elected officials that this is a good way to plan, and the payoff is in the long run.”

Armando Carbonell, chair of the Department of Planning and Urban Form at the Lincoln Institute, says that, in an era when factors like climate change are now in play, planners and the public must increasingly rethink the way they conceptualize the future. “The key is how one thinks about uncertainty,” he says. “We’re better off to accept uncertainty, and the fact that uncertainty is irreducible. We need to learn to live with uncertainty, which is not at all a comfortable position for people and planners.”

The process can be, so to speak, “longer in the short run,” Avin notes, yet it’s “shorter in the long run,” as communities strategize based on realistic conditions. “It may be more rigorous and difficult, but it pays off because you have explored a range of outcomes that protect you from the future to some degree,” he says.

The Lincoln Institute’s 2014 working paper “Exploratory Scenario Planning: Lessons Learned from the Field,” authored by Eric J. Roberts of the Consensus Building Institute, provides some preliminary insights gleaned from a variety of other projects nationally, focusing both on what worked well in other contexts and typical challenges encountered. The process design and scenario framing work are often rated highly by participants, Roberts finds, but the capacity of the convening organization must be up to the demanding challenges.

An Adaptive and Evolving Tool

Step back from the Colorado project and other recent pilot applications, and it becomes clear that the migration of exploratory scenario planning into mainstream land planning is still far from complete, despite its power and potential. Part of the solution is wider dissemination and increased access to the method’s instruments. The Lincoln Institute’s 2012 report Opening Access to Scenario Planning Tools surveys the evolving landscape. It notes, “The emergence of new and improved scenario planning tools over the last 10 years offers promise that the use of scenario planning can increase and that the goal of providing open access to the full potential of scenario planning tools is within reach.”

One of the report’s coauthors, Ray Quay, a researcher with the Decision Center for a Desert City at Arizona State University, says that he has been using the exploratory scenario planning methodology for 20 years now. While he sees it being used by planners in the resource, water, and forestry communities, it has not yet taken hold among land planners and urban planners. “I think there are certainly situations where it can be very useful,” Quay says.

Another barrier to wider adoption is the general failure to distinguish the methodology from other, more familiar kinds of scenario planning, according to Carbonell of the Lincoln Institute. “When you say ‘scenario planning’ to most people in the planning world, they think of Envision Utah—the big regional vision plans that got people to agree on some preferred vision of the future,” he says.

The intellectual “genealogy” of XSP traces back to the Global Business Network in the early 1990s, and its deepest roots lie in the scenario planning work of Royal Dutch Shell—which, as legend has it, produced very successful strategies, Carbonell notes. “The challenge is taking it out of the world of corporate planning and business strategy and getting participation by more than a few wonks,” he says. “That’s why working on the method, making it more accessible and efficient, is important.”

Overall, the challenge remains to bring the methodology fully into the planning world. “I think we’re primarily trying to do two things,” says Carbonell. “We’re trying to transfer a business planning model to a community planning model, so there are definitely differences in governance and the number of people to deal with. The other thing is scale, the size of the community and the area you deal with. Scenario planning has really come more out of the regional level.”

The pertinent questions will be whether or not smaller-scale communities have the expertise, data, and willingness to participate; but ultimately it will be about whether XSP is “appropriate to the decisions being made,” Carbonell says.

As exploratory scenario planning is used more often in regional and urban planning, further best practices will certainly emerge. And the methods of devising strategies in the final phase of XSP may vary from situation to situation. Summer Waters, program director of Western Lands and Communities, says, “The resulting strategies have to be politically acceptable. That is to say, the people we work with have to be able to convince their constituents to buy in.”

Quay says the process leading to the production of scenarios through XSP has been largely “perfected” at this point. But there’s work to be done on the final step of identifying actions that address multiple scenarios and formulating an appropriate strategy. “The problem is that distilling the strategic insights … has been different on all the projects I’ve worked on,” Quay says. “There’s both structure and art within it.”

Avin, of the University of Maryland, agrees that some aspects of these powerful methods are still being worked out. But that’s no reason, he argues, to delay their adoption. “XSP is not supported by tools and models in the way that visioning is supported,” he says. But enough scenarios have been developed that planners can benefit from considering them and adapting them, rather than starting from scratch, he says.

For examples of parallel work in another field, experts note some of the advanced scenario work by the Transportation Resource Board and the associated software tool developed, Impacts 2050. Planners interested in more context and examples will find a diversity of deep sources in the Lincoln Institute’s 2007 book Engaging the FutureShaping the Next One Hundred YearsJournal of the American Planning Association.

Exploratory scenario planning may have been slow to diffuse into the area of land planning, but its offerings are increasingly accessible and useful. “This is a fast-evolving field in terms of tools,” Avin says.

John Wihbey is an assistant professor of journalism and new media at Northeastern University. His writing and research focus on issues of technology, climate change, and sustainability.

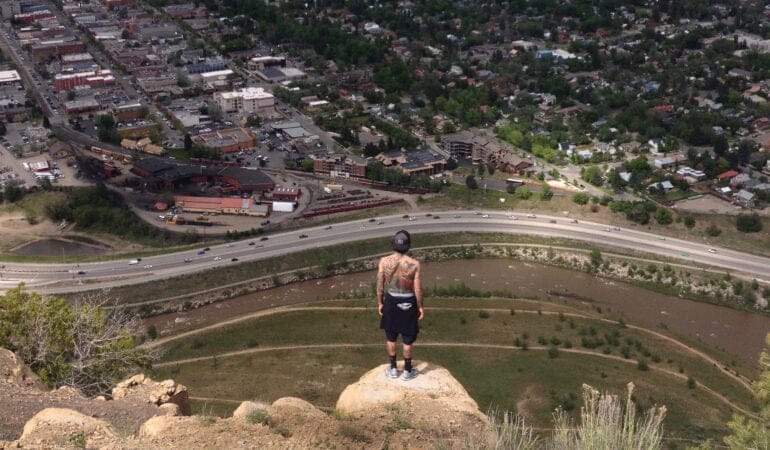

Photograph: Michele Zebrowitz

References

Roberts, Eric J. 2014. “Exploratory Scenario Planning: Lessons Learned from the Field.” Working paper. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Holway, Jim. C. J. Gabbe, Frank Hebbert, Jason Lally, Robert Matthews, and Ray Quay. 2012. Opening Access to Scenario Planning Tools. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Hopkins, Lewis D., and Marisa A. Zapata. 2007. Engaging the Future: Forecasts, Scenarios, Plans, and Projects. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Lempert, Robert J., Steven W. Popper, Steven C. Bankes. 2003. Shaping the Next One Hundred Years: New Methods for Quantitative, Long-Term Policy Analysis. RAND.

Quay, Ray. 2010. “Anticipatory Governance: A Tool for Climate Change Adaptation.” Journal of the American Planning Association 76(4).

“Being a migrant worker for 13 years, I have longed to own a home and live a normal family life here in Shenzhen,” said Mr. Wang, a former farmer from Sichuan Province who now earns 3,100 yuan (US$500) per month in the manufacturing sector of this sprawling city in South China. Wang recently purchased what is known as “small property rights” (SPR) housing—an illegal but widespread type of residential development built by villagers on their collectively owned land in peri-urban areas and urban villages, rural settlements surrounded by modern development in many Chinese cities. While no official statistics are available, the number of SPR units is estimated at 70 million—perhaps one-quarter of all housing units in urban China (Shen and Tu 2014). “Small property rights housing fulfills my need,” continued Mr. Wang. “It’s affordable. It is the best choice for me,” he says.

Sold primarily to individuals without local household registration, or hukou (box 1), SPR housing violates China’s Land Administration Law, which stipulates that only the state, represented by municipal governments, has the power to convert rural land into urban use. Unlike buyers of legally built homes, buyers of SPR housing do not receive a property rights certificate from the housing administration agency of the municipal government; they sign only a property purchase contract with the village committee. Because Chinese laymen often see the state as the “big” institution, housing units purchased from village committees are popularly called “small” property rights housing.

Box 1: China’s Hukou System

China is phasing out its household registration system called hukou, which dates to the 1950s. Hukou identifies a citizen as a resident of a particular locality and entitles the hukou holder to the social security, public schools, affordable housing, and other public services provided by their district, township, or village. Many urban public services are available only to urban hukou holders. Because most migrant workers hold rural hukou, they are ineligible for many public services in the cities where they work and live. Moreover, they have to return to their registered places of residence to apply for marriage certificates, passports, personal ID card renewals, and other documents—a requirement that comes at significant cost and inconvenience.

The widespread development of SPR housing raises a number of legal, political, social, and economic concerns that have prompted academic study and heated public policy debates (Shen and Tu 2014; Sun and Ho 2015). Why has SPR housing emerged in China where administrative control is generally considered tight? What drove the village committees to develop SPR housing in violation of the Land Administration Law? Do SPR housing buyers worry about their tenure security? Why has the government so far tolerated SPR housing ownership? To find answers, one has to look at a number of factors contributing to the rise of SPR housing, including China’s land management system, municipal finance, and public attitudes toward laws and regulations.

The Rise of Small Property Rights Housing

The pace of China’s urbanization is unprecedented. Between 1978 when economic reform began and 2014, the urban population more than quadrupled from 173 million to 749 million, with average annual growth of 16 million. In official counts, the urban population includes residents with hukou and, in recent years, migrants who stay in a city for more than six months. Amid such explosive growth, the government’s institutional capacity to manage urbanization has often lagged behind, at best barely responding to emerging issues.

“The informal development of SPR housing is regarded as an extra-legal practice and a type of spontaneous urbanization,” wrote Dr. Liu Shouying, a senior researcher with the Development Research Center of the State Council, in his newly published book, Land Issues in the Transitional China (Liu 2014).

“There is no law explicitly addressing the emerging issues of SPR housing,” said Peking University Professor Zhou Qiren, a well-known property rights scholar in China (Zhou 2014).

Legal and Economic Factors

Under China’s dual land management system, urban land is owned by the state, and rural land is collectively owned by the villages (figure 1). There is no private ownership. Only the state has the legal power to expropriate rural land and convert it to urban use. Villages have no land development rights. Compensation to villages for expropriated rural land is based on the land’s agricultural production value rather than its higher market value.

When the state expropriates rural land for urban use, it allocates it to residential and commercial uses through concessions to real estate developers, who pay a fee for land use rights. This system allows municipal governments to expropriate rural land for industrial and urban development at low costs, and to generate handsome revenues from land concessions.

The municipal governments’ ability to expand the urban land supply is heavily limited, however, by China’s strict farmland preservation requirements. Under this policy, 1.8 billion mu (equivalent to 1.2 million sq. km) of high-quality agricultural land nationwide must be reserved for food security. The Ministry of Land and Resources annually approves the amount of urban land for each city, and the municipal government then allocates this supply to various purposes, leaving a small fraction (usually around 30 percent) for residential development. Given the limited supply of residential land in the major cities, prices are bid up very high.

By contrast, most cities offer industrial land to manufacturing firms at very low and subsidized prices in order to compete for investment and employment. They expect these firms to yield jobs, economic growth, and tax revenues for the municipality, and then for those new jobs to generate increased demand for housing and services—in turn creating more jobs, economic growth, and tax revenues. As a result, the price for residential land is up to 15 times higher than the price of industrial land (figure 2).

Over the last few years, concession fees from commercial and residential land were typically as high as 40 to 60 percent of municipal tax revenues. With these revenues, municipal governments not only subsidize industrial land, but also fund public investment in infrastructure and other services. Because farmers’ compensation was only a tiny fraction of the value created from the state-monopolized development rights, they were keen to find ways to share in these revenues, setting the stage for SPR housing.

There are three types of rural land in China: one is used for agriculture, one is used for construction, and the third is unused. SPR housing units are usually built on rural construction land, which allows for villagers’ residential plots and public facilities. While strict enforcement of the national farmland preservation policy generally prevents conversion of agricultural land into construction land, villages are not explicitly prohibited from using construction land for village industries, restaurants, hotels, warehouses, rental plants, and rental housing. Indeed, property rental businesses have existed in rural areas for many years. For example, rural households living in urban villages and at the rapidly growing urban fringe have built multi-story housing on their residential plots and rented the units to migrant workers.

When urban housing prices started to soar in the mid-2000s, the villages saw opportunities to make handsome profits from building and selling homes. Each year from 2006 to 2014, house prices climbed about 20 percent in Beijing, 18 percent in Shanghai, 17 percent in Shenzhen, and 11 percent in Chengdu (PLC-HLCRE 2014). The rapidly rising prices of residential land drove part of these increases.

Demand for home ownership in China remains strong, thanks to the growing urban population, rising household incomes, high savings rates among urban households, and lack of alternative household investments. And SPR housing units are much less expensive than comparable formal housing units in the same location. Indeed, their prices are typically 40 percent to 60 percent cheaper, because villages do not pay land concession fees as the urban real estate developers do, and the administrative costs of providing SPR housing are also lower. Thus, SPR units became the rational housing choice for many migrant households, and even for some urban households with hukou in their city of residence.

Social and Cultural Factors

The village committees understood that building and selling SPR housing violated the Land Administration Law and the associated local land regulations, but the lure of profits drove them to test the legal limits. And once a few villages started selling SPR housing, others were quick to follow. The central government responded by issuing a series of administrative circulars calling for a halt, but took little action due to the lack of legally effective and socially acceptable measures to put an end to the practice.

Meanwhile, given the lack of legal protections, one might ask why SPR housing buyers do not opt for rental housing. The answer is that the rental market in urban China is poorly regulated, and contract enforcement is weak. Tenants often face the risk of unexpected rent hikes and premature termination of leases. In addition, participation in the affordable housing programs run by the municipal governments is not an option for most migrant workers because they do not have local urban hukou.

At the same time, Chinese households strongly prefer home ownership for a number of social and cultural reasons. Most households consider a stable home essential to their lives. As Dr. Sun Yet Sen (1866–1925) famously said: “Every household ought to have a home.” The Chinese word for “family” (jia) is literally the same as the word for “home,” both in written form and speech. Most Chinese think that an ideal home is a secure place for the family, and the most secure home is a self-owned one. One SPR housing buyer in Shenzhen said, “With my newly purchased SPR housing unit, I don’t have to worry about being forced out of the rented unit any more, and I could make my own place a real home.”

Because healthcare and educational opportunities are better in cities than in rural areas, many migrant workers purchase SPR housing units so that their families can take advantage of these services. And for young men, buying SPR housing units is a way to improve their chances in the highly competitive marriage market, where men outnumber women by 34 million, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. Moreover, herding behavior—where everyone wants to do what everyone else does—is a significant factor, and the housing purchases of some buyers heavily influence the purchase decisions of others.

As some newspaper interviews and Internet surveys reveal, buyers generally do not worry about being prosecuted for living in SPR housing. They do not believe that the government would attempt to enforce the law on millions of citizens. There is a popular saying in the Chinese legal enforcement tradition: fa bu ze zhong (the law does not punish everyone). If many people violate a law or a regulation in China, people often consider the law itself flawed.

Indeed, over the history of economic reform in China, there are celebrated cases in which mass violation of a law drove change, resulting in legalization of formerly prohibited activities. Based on this history, many SPR housing buyers expressed confidence that the government would not evict them from their homes. This confidence is evident from the fact that SPR housing owners often spend a substantial amount of their incomes, savings, or borrowed money on home improvements such as interior decoration and furnishings.

Many SPR housing owners feel that they are already a large enough group to defy any government actions that penalize them. Eviction is highly unlikely, given that the Chinese government’s top priority is maintaining social stability. One SPR housing owner in Beijing said, “I am sure that the government will not evict us from our homes. If it happens, where should we live? In front of the municipal hall?”

A Major Challenge to Government

Enforcing the law against SPR housing development on millions of households would indeed be politically unwise. Doing so would likely trigger social unrest—the last thing the government wants to see. However, amending the law is not easy, and for some time the central government seemed unable to come up with a land management system suitable for an urbanized China. Without a clear solution, the central government thus tended to tolerate SPR housing.

Local governments, however, were more uncomfortable with the growing numbers of SPR housing units because they reduced demand for government-supplied residential land and therefore revenues from land concessions. But again, the fear of social unrest left most local governments with nothing to do but repeat the central government’s rhetoric about its illegality. Government tolerance also reflects the fact that SPR housing developments afford shelter for many lower- and middle-income groups that the government and the market have been unable to provide. In the public debate, the argument for SPR housing is that it serves an important social function by housing the large number of migrant workers essential to China’s rapid urban economic growth.

Perhaps the bigger concern for government is the impacts of SPR housing development on real estate markets, municipal finance, and future urban forms. As it is, the formal urban housing market is already in over-supply. Additional provision of SPR housing units would further weaken formal market demand and increase bank credit risk. Moreover, China’s city planning efforts do not cover rural land outside designated planning areas. The spread of SPR housing in these areas would therefore lead to undesirable urban development patterns.

Recommended Reforms

In recognition of the root causes of SPR housing development, the Third Plenary Session of the Communist Party of China’s 18th Central Committee issued a document in November 2013 spelling out directions for a set of reforms directly related to land, hukou, and municipal finance.

On land: Integrate the urban and rural construction land markets. Allow the sale, leasing, and shareholding of rural, collectively owned construction land under the premise that it conforms to planning. . . . Reduce land expropriation that does not promote public welfare.

On hukou: Accelerate the reform of the hukou system to help farmers become urban residents. . . . Efforts should be made to make basic urban public services (such as affordable housing and the social safety net) available to all permanent residents in cities, including rural residents who have migrated to cities.

On municipal finance: Improve the taxation system and expand the local tax base by gradually raising the share of direct taxation (mainly the personal income tax and property tax). . . . Accelerate property tax legislation.

These reform efforts aim to dismantle the dual system of land management, allowing villages to share in the benefits of land development and raising the transaction costs of land expropriation. The hukou system will be phased out gradually, starting in the smaller cities. While detailed actions on these two reform fronts are now being worked out or tested in pilot programs, municipal finance reform remains a major concern. If the scope of land concessions is reduced and the hukou system is dismantled, cities will see significant reductions in land sales revenues and increases in public expenditures for providing services to migrant workers and their families.

While residential property taxes are expected to become a new source of municipal revenues, this change will not occur immediately. Indeed, the central government is currently drafting the property tax law, and it may be at least two years before its passage by the National People’s Congress. Since it will also take a few years for cities to establish assessment systems, residential property taxation will not support municipal budgets for some time. Nevertheless, there is hope that this new round of policy reform will properly address the critical issue of SPR housing.

Li Sun is a postdoctoral researcher at Delft University of Technology, Netherlands, and an affiliated researcher with Peking University–Lincoln Institute Center for Urban Development and Land Policy.

Zhi Liu is senior fellow and director of the Lincoln Institute’s China Program, as well as director of the Peking University–Lincoln Institute Center for Urban Development and Land Policy.

References

Liu, Shouying. 2014. Land Issues in the Transitional China. Beijing: China Development Press.

Liu, Zhi, and Jinke Wang. 2014. “An Analysis of China’s Urbanization, Land and Housing Problems.” In Annual Report on the Development of China’s New Urbanization, Li Wei, Song Min, and Shen Tiyan, eds. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press (China).

PLC-HLCRE. 2014. “Report on the China Quality-Controlled Urban Housing Price Indices (CQCHPI).” Beijing: Peking University–Lincoln Institute Center for Urban Development and Land Policy (PLC) and Hang Lung Center for Real Estate (HLCRE), Tsinghua University.

Shen, Xiaofang, and Fan Tu. 2014. “Dealing with ‘Small Property Rights’ in China’s Land Market Development: What Can China Learn from Its Past Reforms and the World Experience?” Working paper. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Sun, Li, and Peter Ho. 2015. “An Emerging Phenomenon of Informal Settlement in China: Small Property Rights Housing in Urban Villages and Peri-urban Areas.” Paper presented at the Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty (March 23–27).

Zhou, Qiren. 2014. “The Reform Should Not Be Self-limited” (in Chinese). http://heschina.org/archives/3211.html

Before joining the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, I covered the Detroit beat for almost a decade for the Ford Foundation. There I was able to witness firsthand the unprecedented challenges involved in reversing the fortunes of the most powerful and important U.S. city of the mid-20th century. The enormity of these challenges called forth a coalition of some of the best and brightest community rebuilders with whom I’ve had the privilege to work. The quality and commitment of this strident group of public servants, civic and community leaders, and private-sector visionaries helped Detroit reclaim a bright future.

Signature efforts of this unique public-private-philanthropic partnership (a P4!) included the planning, construction, and funding of Detroit’s first public transit investment in more than five decades—the M1 Rail, which broke ground in July 2014 using a pooled private investment of more than $100 million. Leadership for the effort did not simply build a symbolic 3.3-mile light rail line along Woodward Avenue, the spine of the city, it also leveraged the private investment to secure a commitment from state and national governments to launch the region’s first transit authority.

Local and national philanthropic leaders also assembled more than $125 million to launch the New Economy Initiative—a decade-long effort to rekindle an entrepreneurial ecosystem in the region through strategic incubation of hundreds of new businesses, thousands of new jobs, and enduring long-term collaboration among employers and workforce developers. And, in what might be their most controversial and heroic collective effort, these philanthropies worked with the State of Michigan to assemble more than $800 million for “the Grand Bargain,” which saved both the legendary collection of the Detroit Institute of the Arts from the auction block and the future pensions of Detroit’s public servants.

Stunningly, while social entrepreneurs did gymnastics to bring hundreds of millions of dollars in support to Detroit, the city reportedly returned similar amounts in unspent formula funds to the federal government. A city with more than 100,000 vacant and abandoned properties and unemployment rates hovering close to 30 percent could not find a way to use funds that were freely available; the city needed only to ask for them and monitor their use. Beleaguered Detroit public servants, whose ranks were decimated by population loss and the city’s fiscal insolvency, did not have the capacity or the systems to responsibly manage or comply with federal funding rules. And, in this regard, Detroit is not unique among legacy cities or other fiscally challenged places.

A March 2015 report from the Government Accountability Office, Municipalities in Fiscal Crisis (GAO-15-222), looked at four cities that filed for bankruptcy (Camden, NJ; Detroit, MI; Flint, MI; and Stockton, CA) and concluded that the cities’ inability to use and manage federal grants was attributable to inadequate human capital capacity, staffing shortages, diminished financial capacity, and outdated information technology systems. The report lamented that not only were the cities unable to use formula funds—like Community Development Block Grants that are distributed according to objective criteria such as population size and need—but they routinely forwent applying for competitive funding, as well. A separate 2012 analysis by Senator Tom Coburn (R-OK), Money for Nothing, identified some $70 billion in federal funds that were unspent “due to poorly drafted laws, bureaucratic obstacles and mismanagement, and a general lack of interest or demand from the communities to which this money was allocated.”

How can it be that the neediest places are unable to use the assistance that is available? It’s unsurprising that a city like Detroit, which lost almost two-thirds of its population over six decades, would see diminished staffing and staff capacity in city offices. It is also unsurprising that Detroit did not have state-of-the-art IT systems. When a municipality faces fiscal challenges, infrastructure always gets short shrift. The inability to make use of allocated funding probably isn’t a sin of commission, but a regrettable omission that runs deeper, and needs fixing. But where to start? Let’s see what the data tells us. Which formula programs have the weakest throughput? Where are the places with the worst uptake? By all accounts, we don’t know. If federal agencies know which programs and places might make the best and worst lists, they are not reporting it. Moreover, most citizens in Detroit, who bear one of the highest property tax rates in the country, don’t know that their city is leaving tens of millions of dollars of federal money on the table each and every year.

Last summer, with little fanfare but great ambition, the Lincoln Institute launched a global campaign to promote municipal fiscal health. The campaign focuses attention on several drivers of municipal fiscal health, including the role of land and property taxation to provide a stable and secure revenue base. In this issue of Land Lines, we consider ways that cities and regions are building new capacities—reliable fiscal monitoring and transparent stewardship of public resources, effective communication and coordination among local, county, state, and federal governments—to overcome major economic and environmental barriers. We focus on how places are looking inside and outside their borders to enlist the assistance of others. Hopefully, these stories will inspire us to work toward broader, deeper, and more creative ways to thrive together rather than struggling alone.

Two technology-based tools featured in this issue are changing the way municipal finance information is organized and shared. They empower citizens and voters to hold their community leaders accountable and ensure that once we throw the assistance switch, the circuit is completed. PolicyMap (p. 18) was founded with the goal of supporting data-driven public decisions. Researchers there have organized dozens of public data sets and developed a powerful interface where users can view the data on maps. It includes thousands of indicators that track the use of public funds and their impact. The city of Arlington, Massachusetts, has demystified its city finances through the Visual Budget (p. 5), an open-source software tool that helps citizens understand where their tax dollars are spent. PolicyMap and the Visual Budget have the potential to follow all revenue sources and expenditures for a city and make them transparent to taxpayers. For cities or federal agencies willing to disclose this information, these social enterprises stand ready to track and report on the use, or non-use, of public funds.

Vertical alignment of multiple levels of government toward the goal of municipal fiscal health is not only a domestic remedy. Our interview with Zhi Liu (p. 30) reports on the efforts of the central government of the People’s Republic of China to build a stable revenue base under local governments through enactment of a property tax law, an action to help municipal governments survive the shifting sands of land reform.

In our report on the Working Cities Challenge (p. 25), researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston identify what is possibly the most important capacity needed to promote not only municipal fiscal health, but thriving, sustainable, and resilient places: leadership. Leadership—which might come in the form of visionary public officials, bold civic entrepreneurs, or gritty peripatetic academics—is at the core of other inspiring cases reported in this issue. Leaders in Chattanooga (p. 8) made a big bet on infrastructure—low-cost, ultra-high-speed Internet, provided through a municipal fiber-optic network—to help the city complete its transition from polluted industrial throwback to clean, modern tech hub. And it’s working.

The Super Ditch (p. 10) is another example of multiple governments working with private parties to forge creative solutions to joint challenges. The Super Ditch is innovating urban-agricultural water management through new public-private agreements that interrupt the old “buy and dry” strategies practiced by water-starved cities—continuing to meet municipal water demand without despoiling prime farmland.

Before we endure endless partisan bickering about whether national governments should rescue bankrupt cities, perhaps we should find a way to ensure that they don’t go bankrupt in the first place, by using the help that we’ve already promised. Only a sadist or a cynic would intentionally dangle resources out of the reach of needy people or places. If we invest only a fraction of unspent funds to build the right local capacities, communities will be able to solve their own problems. Whether it is a P4, an innovative technology tool, or a new way of working among governments and the private sector, social entrepreneurs are amplifying human ingenuity to help us overcome the biggest challenge we face: finding new ways to work together so that we do not perish alone.