La Bahía de Chesapeake es un icono cultural, un tesoro nacional y un recurso natural protegido por cientos de agencias, organizaciones sin fines de lucro e instituciones. Ahora, una nueva tecnología de construcción de mapas digitales con exactitud sin precedentes, desarrollada por The Chesapeake Conservancy y respaldada por el Instituto Lincoln de Políticas de Suelo, está identificando con precisión contaminación y otras amenazas a la salud del ecosistema de la bahía y su cuenca, que abarca 165.000 km2, 16.000 km de costa y 150 ríos y arroyos importantes. Con una resolución de un metro por un metro, la tecnología de mapas de “conservación de precisión” está llamado la atención de una amplia gama de agencias e instituciones, que ven aplicaciones potenciales para una variedad de procesos de planificación en los Estados Unidos y el resto del mundo. Este nuevo juego de datos de cubierta de suelo, creado por el Centro de Innovación de Conservación (CIC) de The Conservancy, tiene 900 veces más información que los juegos de datos anteriores y brinda mucho más detalle sobre los sistemas naturales y las amenazas medioambientales a la cuenca, de las que la más persistente y urgente es la contaminación de las aguas de la bahía, que afecta desde la salud de la gente, las plantas y la vida silvestre hasta la industria pesquera, el turismo y la recreación.

“El gobierno de los EE.UU. está invirtiendo más de US$70 millones al año para limpiar la Bahía de Chesapeake, pero no sabe qué intervenciones tienen el mayor impacto”, dice George W. McCarthy, presidente y director ejecutivo del Instituto Lincoln. “Con esta tecnología podremos determinar si las intervenciones pueden interrumpir el flujo superficial de nutrientes que está provocando el florecimiento de algas en la bahía. Podremos ver dónde fluye el agua a la Bahía de Chesapeake. Podremos ver el rédito del dinero invertido, y podremos comenzar a reorientar a la Agencia de Protección Ambiental (EPA, por su sigla en inglés), el Departamento de Agricultura y múltiples agencias que quizás planifiquen en forma estratégica pero sin comunicarse entre sí”.

The Chesapeake Conservancy, una organización sin fines de lucro, está dando los toques finales a un mapa de alta resolución de toda la cuenca para el Programa de la Bahía de Chesapeake. Ambas organizaciones están ubicadas en Annapolis, Maryland, el epicentro de los esfuerzos de conservación de la bahía. El programa presta servicio a la Asociación de la Bahía de Chesapeake (Chesapeake Bay Commission), la EPA, la Comisión de la Bahía de Chesapeake y los seis estados que alimentan la cuenca: Delaware, Maryland, Nueva York, Pensilvania, Virginia, West Virginia y el Distrito de Columbia, junto con 90 contrapartes más, entre las que se cuentan organizaciones sin fines de lucro, instituciones académicas y agencias gubernamentales como la Administración Nacional Oceánica y Atmosférica, el Servicio de Peces y Vida Silvestre de los EE.UU., el Servicio Geológico de los EE.UU. (USGS) y el Departamento de Defensa de los EE.UU.

En nombre de esta alianza, la EPA invirtió US$1,3 millones en 2016 en financiamiento estatal y federal para el proyecto de cubierta de suelo de alta resolución de The Conservancy, que se está desarrollando en conjunto con la Universidad de Vermont. La información obtenida de los diversos programas piloto de mapas de precisión ya está ayudando a los gobiernos locales y contrapartes fluviales a tomar decisiones de gestión de suelo más eficientes y económicas.

“Hay muchos actores en la cuenca de la Bahía de Chesapeake”, dice Joel Dunn, presidente y director ejecutivo de The Chesapeake Conservancy. “La comunidad ha estado trabajando en un problema de conservación muy complicado por los últimos 40 años, y como resultado hemos creado capas y capas y muchas instituciones para resolver este problema”.

“Ahora no es un problema de voluntad colectiva sino un problema de acción, y toda la comunidad tiene que asociarse de maneras más innovadoras para llevar la restauración de los recursos naturales de la cuenca al próximo nivel superior”, agrega.

“La tecnología de conservación está evolucionando rápidamente y puede estar llegando ahora a su cima”, dice Dunn, “y queremos montarnos sobre esa ola”. El proyecto es un ejemplo de los esfuerzos de The Conservancy para llevar su trabajo a nuevas alturas. Al introducir “big data” (datos en gran volumen) en el mundo de la planificación medioambiental, dice, The Conservancy se preparar para innovar como un “emprendedor de conservación”.

¿Qué es la tecnología de mapas de precisión?

Los datos del uso del suelo y la cubierta del suelo (LULC, por su sigla en inglés) extraídos de imágenes por satélite o desde aviones son críticos para la gestión medioambiental. Se usa para todo, desde mapas de hábitat ecológico hasta el seguimiento de tendencias de desarrollo inmobiliario. El estándar de la industria es la Base de Datos Nacional de Cubierta de Suelo (NLCD, por su sigla en inglés) de 30 m por 30 m de resolución del USGS, que proporciona imágenes que abarcan 900 m2, o casi un décimo de hectárea. Esta escala funciona bien para grandes áreas de terreno. No es suficientemente exacta, sin embargo, para proyectos de pequeña escala, porque todo lo que tenga un décimo de hectárea o menos se agrupa en un solo tipo de clasificación de suelo. Una parcela podría ser clasificada como un bosque, por ejemplo, pero ese décimo de hectárea podría tener también un arroyo y humedales. Para maximizar las mejoras en la calidad del agua y los hábitats críticos, hacen falta imágenes de mayor resolución para poder tomar decisiones a nivel de campo sobre dónde vale la pena concentrar los esfuerzos.

Con imágenes aéreas públicamente disponibles del Programa Nacional de Imágenes de Agricultura (NAIP, por su sigla en inglés), en combinación con datos de elevación del suelo de LIDAR (sigla en inglés de Detección y Medición de Distancia por Luz), The Conservancy ha creado juegos de datos tridimensionales de clasificación del suelo con 900 veces más información y un nivel de exactitud de casi el 90 por ciento, comparado con el 78 por ciento para la NLCD. Esta nueva herramienta brinda una imagen mucho más detallada de lo que está ocurriendo en el suelo, identificando puntos donde la contaminación está ingresando en los arroyos y ríos, la altura de las pendientes, y la efectividad de las mejores prácticas de gestión (Best Management Practices, o BMP), como sistemas de biofiltración, jardines de lluvia y amortiguadores forestales.

“Podemos convertir las imágenes vírgenes en un paisaje clasificado, y estamos entrenando a la computadora para que vea lo mismo que los seres humanos al nivel del terreno”, incluso identificando plantas individuales, dice Jeff Allenby, Director de Tecnología de Conservación, quien fue contratado en 2012 para aprovechar la tecnología para estudiar, conservar y restaurar la cuenca. En 2013, una subvención de US$25.000 del Consejo de Industrias de Tecnología Informática (ITIC) permitió a Allenby comprar dos computadoras poderosas para comenzar el trabajo de trazar mapas digitales. Con el respaldo del Programa de la Bahía de Chesapeake, su equipo de ocho expertos en sistemas de información geográfica (SIG) ha creado un sistema de clasificación para la cuenca de la Bahía de Chesapeake con 12 categorías de cubierta de suelo, como superficies impermeables, humedales, vegetación de baja altura y agua. También está incorporando información de zonificación de los usos del suelo provista por el Programa de la Bahía de Chesapeake.

El potencial de la tecnología

El trazado de mapas de precisión “tiene el potencial de transformar la manera de ver y analizar sistemas de suelo y agua en los Estados Unidos”, dice James N. Levitt, Gerente de Programas de Conservación de Suelo del Departamento de Planificación y Forma Urbana del Instituto Lincoln, que está respaldando el desarrollo tecnológico de The Conservancy con una subvención de US$50.000. “Nos ayudará a mantener la calidad del agua y los hábitats críticos, y ubicar las áreas donde las actividades de restauración pueden tener el mayor impacto sobre el mejoramiento de la calidad del agua”. Levitt dice que la tecnología permite convertir fuentes de contaminación “no puntuales”, o sea difusas e indeterminadas, en fuentes “puntuales” identificables específicas sobre el terreno. Y ofrece un gran potencial de uso en otras cuencas, como la de los sistemas de los ríos Ohio y Mississippi, los que, como la cuenca de Chesapeake, también tienen grandes cargas de escurrimiento contaminado de aguas de tormenta debido a actividades agrícolas.

Es un momento propicio para hacer crecer la tecnología de conservación en la región de Chesapeake. En febrero de 2016, la Corte Suprema de los EE.UU. decidió no innovar en un caso que disputaba el plan de la Asociación de la Bahía de Chesapeake para restaurar plenamente la bahía y sus ríos de marea, para poder volver a nadar y pescar en ellos para 2025. Esta decisión de la Corte Suprema dejó en su lugar un dictamen de la Corte de Apelación del 3.er Circuito de los EE.UU. que confirmó el plan de aguas limpias y mayores restricciones sobre la carga máxima total diaria, o el límite de contaminación permisible de sustancias como nitrógeno y fósforo. Estos nutrientes, que se encuentran en los fertilizantes agrícolas, son los dos contaminantes principales de la bahía, y son tenidos en cuenta bajo las normas federales de calidad del agua establecidas en la Ley de Agua Limpia. El dictamen también permite a la EPA y a agencias estatales imponer multas a aquellos que contaminan y violan las reglamentaciones.

La calidad del agua de la Bahía de Chesapeake ha mejorado desde su fase de mayor contaminación en la década de 1980. Las modernizaciones y la explotación más eficiente de las plantas de tratamiento de aguas servidas han reducido la cantidad de nitrógeno que ingresa en la bahía en un 57 por ciento, y el fósforo en un 75 por ciento. Pero los estados de la cuenca siguen violando las regulaciones de agua limpia y el aumento del desarrollo urbano exige una evaluación constante y una reducción de la contaminación en el agua y hábitats críticos.

Proyecto piloto núm. 1: El río Chester

The Conservancy completó una clasificación de suelo de alta resolución y análisis de escurrimiento de aguas de tormenta para toda la cuenca del río Chester, en la costa oriental de Maryland, con financiamiento de las Campañas de Energía Digital y Soluciones de Sostenibilidad de ITIC. Isabel Hardesty es la cuidadora del río Chester, de 100 km de largo, y trabaja con la Asociación del río Chester, con asiento en Chestertown, Maryland. (“Cuidadora de río” es el título oficial de 250 individuos en todo el mundo que son los “ojos, oídos y voz” de un cuerpo de agua.) El análisis de The Conservancy ayudó a Hardesty y su personal a comprender dónde fluye el agua a través del terreno, dónde serían más efectivos las BMP y qué corrientes fluviales degradadas sería mejor restaurar.

Dos tercios de la cubierta del suelo en la cuenca del río Chester son cultivos en hilera. Los agricultores de estos cultivos frecuentemente usan fertilizante en forma uniforme en todo el campo, y el fertilizante se escurre con las aguas de tormenta de todo el predio. Esto se considera contaminación no puntual, lo cual hace más difícil identificar el origen exacto de los contaminantes que fluyen a un río, comparado, por ejemplo, con una pila de estiércol. El equipo de The Conservancy trazó un mapa de toda la cuenca del río Chester, identificando dónde llovió en el terreno y dónde fluyó el agua.

“A simple vista se puede mirar un campo y ver dónde fluye el agua, pero este análisis es mucho más científico”, dice Hardesty. El mapa mostró la trayectoria del flujo de agua en toda la cuenca, en rojo, amarillo y verde. El color rojo identifica un mayor potencial de transporte de contaminantes, como las trayectorias de flujo sobre superficies impermeables. El color verde significa que el agua está filtrada, como cuando fluye a través de humedales o un amortiguador forestal, reduciendo la probabilidad de que transporte contaminantes. El amarillo es un nivel intermedio, que indica que podría ser uno u otro. El análisis se tiene que “comprobar en la realidad”, dice Hardesty, o sea que el equipo usa análisis SIG a nivel de cada granja para confirmar lo que está ocurriendo en un campo específico.

“Somos una organización pequeña y tenemos relaciones con la mayoría de los agricultores de la zona”, dice Hardesty. “Podemos mirar una parcela de terreno y saber qué prácticas está usando el agricultor. Nos hemos comunicado con nuestros terratenientes y colaborado con ellos en sus predios; así sabemos dónde pueden entrar contaminantes a los arroyos. Cuando nos enteramos de que un agricultor en particular quiere poner un humedal en su granja, su uso del suelo y el análisis de flujo de agua nos ayuda a determinar qué tipo de BMP tenemos que usar y dónde tiene que estar ubicado”. El valor de elaborar mapas de precisión para la Asociación del Río Chester, dice Hardesty, ha sido “poder darse cuenta que el mejor lugar para colocar una solución de intercepción de agua es donde sea mejor para el agricultor. En general, esta es una parte bastante poco productiva de la granja”. Dice que en general los agricultores están contentos de poder trabajar con ellos para resolver el problema.

La Asociación del Río Chester también está desplegando tecnología para usar los recursos de modo más estratégico. La organización tiene un programa de monitorización de agua y ha recolectado datos sobre la cuenca por muchos años, que el equipo de The Conservancy ha analizado para clasificar los arroyos de acuerdo a su calidad de agua. La asociación ha hecho ahora análisis SIG que muestra los trayectos de flujo para todas las subcuencas de arroyos, y está creando un plan estratégico para guiar los esfuerzos futuros de limpieza de los arroyos con la peor calidad del agua.

Proyecto piloto núm. 2: Herramienta de informe de BMP del Consorcio de Aguas de Tormenta del Condado de York

En 2013, The Conservancy y otras contrapartes principales lanzaron el programa Envision the Susquehanna (Vislumbrar el Susquehanna) para mejorar la integridad ecológica y cultural del paisaje y la calidad de vida a lo largo del río Susquehanna, desde su cabecera en Cooperstown, Nueva York, hasta su descarga en la Bahía de Chesapeake en Havre de Grace, Maryland. En 2015, The Conservancy seleccionó el programa para su proyecto piloto de datos en el condado de York, Pensilvania.

Pensilvania ha tenido problemas para demostrar progreso en la reducción del escurrimiento de nitrógeno y sedimento, sobre todo en los lugares donde las aguas de tormenta urbanas ingresan en los ríos y arroyos. En 2015 la EPA anunció que iba a retener US$2.9 millones de fondos federales hasta que el estado pudiera articular un plan para alcanzar sus metas. En respuesta, el Departamento de Protección Ambiental de Pensilvania publicó su Estrategia de restauración de la Bahía de Chesapeake para aumentar el financiamiento de proyectos de aguas de tormenta locales, verificar el impacto y los beneficios de BMP locales, y mejorar la contabilidad y recolección de datos para supervisar su efectividad.

El condado de York creó el Programa de Reducción de Contaminación de la Bahía de Chesapeake – Condado de York para coordinar los informes sobre proyectos de limpieza. La tecnología de mapas de precisión de The Conservancy ofreció una oportunidad perfecta para un proyecto piloto: En la primavera de 2015, la Comisión de Planificación del Condado de York y The Conservancy comenzaron a colaborar para mejorar el proceso de selección de los proyectos de BMP para escurrimiento de aguas de tormenta urbana, que cuando se combinan con un aumento de los emprendimientos inmobiliarios, constituyen la amenaza de mayor crecimiento en la Bahía de Chesapeake.

La comisión de planificación seleccionó el proceso de propuesta anual de BMP de 49 de las 72 municipalidades reguladas como “sistemas de alcantarillado de aguas de tormenta municipales separados”, o MS4, por su sigla en inglés. Estos son sistemas de aguas de tormenta requeridos por la Ley de Agua Limpia federal para recolectar el escurrimiento contaminado que de lo contrario fluiría a las vías fluviales locales. La meta de la comisión era normalizar el proceso de presentación y revisión de proyectos. El condado descubrió que las reducciones de carga calculadas no eran correctas en varias municipalidades, porque no contaban con el personal necesario para recolectar y analizar los datos, o usaron una variedad de fuentes de datos distintas. Por consiguiente, a la comisión le resultó difícil identificar, comparar y elaborar prioridades para identificar los proyectos más efectivos y económicos para alcanzar las metas de calidad de agua.

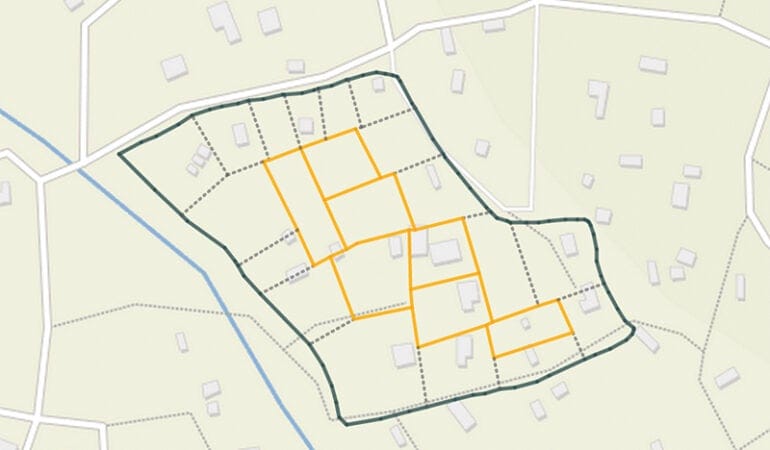

Cómo usar la herramienta de informe de BMP del Consorcio de Aguas de Tormenta del Condado de York

Para usar la herramienta en línea, los usuarios seleccionan un área de proyecto propuesta, y la herramienta genera automáticamente un análisis de la cubierta del suelo de alta resolución para toda el área de drenaje del proyecto. La herramienta integra estos datos de alta resolución, por lo que los usuarios pueden evaluar cómo sus proyectos podrían interactuar con el paisaje. Los usuarios también pueden comparar proyectos potenciales de manera rápida y fácil, y después revisar y presentar propuestas de proyectos con el mayor potencial para mejorar la calidad del agua. Los usuarios después pueden ingresar la información del proyecto en un modelo de reducción de carga de nutrientes/sedimentos llamado Herramienta de escenario de evaluación de instalaciones de la Bahía, o BayFAST. Los usuarios ingresan información adicional sobre el proyecto, y la herramienta inserta los datos geográficos. El resultado es un informe simple de una página en formato PDF que reseña los costos estimados del proyecto por libra de nitrógeno, fósforo y reducción de sedimento. Puede usar la herramienta en: http://chesapeakeconservancy.org/apps/yorkdrainage.

The Conservancy y la comisión de planificación colaboraron para elaborar una Herramienta de informe de BMP del Consorcio de Aguas de Tormenta del Condado de York de fácil utilización (recuadro, pág. 14), que permite comparar distintos métodos de restauración y cambio en el uso del suelo, y analizarlos antes de ponerlos en práctica. The Conservancy, la comisión y los miembros del personal municipal colaboraron sobre una plantilla uniforme de propuestas y recolección de datos, y optimizaron el proceso con los mismos juegos de datos. Después, The Conservancy capacitó a algunos profesionales SIG locales para que ellos a su vez pudieran proporcionar asistencia técnica a otras municipalidades.

“Se puede usar en forma fácil y rápida”, explica Gary Milbrand, CFM, el ingeniero SIG y Director de Informática de la Municipalidad de York, quien proporciona asistencia técnica de proyecto a otras municipalidades. Anteriormente, dice, las municipalidades típicamente gastaban entre US$500 y US$1.000 en consultores para analizar sus datos y crear propuestas e informes. La herramienta de informe, dice, “nos ahorra tiempo y dinero”.

La comisión requirió a todas las municipalidades reguladas que presentaran sus propuestas de BMP usando la nueva tecnología para el 1 de julio de 2016, y las propuestas de financiamiento se seleccionarán a fines de este otoño. Las contrapartes dicen que las municipalidades están más involucradas en el proceso de describir cómo sus proyectos están funcionando en el entorno, y esperan ver proyectos más competitivos en el futuro.

“Por primera vez podemos hacer una comparación cuantitativa”, dice Carly Dean, gerente de proyecto de Envision the Susquehanna. “El solo hecho de poder visualizar los datos permite que el personal municipal analice cómo interactúan sus proyectos con el terreno, y por qué el trabajo que están realizando es tan importante”. Dean agrega: “Sólo estamos empezando a escarbar la superficie. Pasará un tiempo hasta poder darnos cuenta de todas las aplicaciones potenciales”.

Integración de datos de la cubierta del suelo y el uso del suelo a nivel de parcela

El equipo de Conservación también está trabajando para superponer datos de cubierta de suelo con los datos de condado a nivel de parcela, para proporcionar más información sobre cómo se está usando el suelo. La combinación de imágenes satelitales de alta resolución y datos del uso del suelo del condado a nivel de parcela no tiene precedentes. Los condados construyen y mantienen bases de datos a nivel de parcela en todos los Estados Unidos utilizando información como registros tributarios y de propiedad. Alrededor de 3.000 de los 3.200 condados han digitalizado estos registros públicos. Pero aun así, en muchos de estos condados los registros no se han organizado y normalizado para el uso del público, dice McCarthy.

La EPA y un equipo de USGS en Annapolis han estado combinando datos de la cubierta de suelo de un metro de resolución con datos del uso del suelo para los seis estados de Chesapeake, para brindar una vista amplia a nivel de cuenca que al mismo tiempo proporcione información detallada sobre el suelo desarrollado y rural. Este otoño, el equipo incorporará los datos del uso del suelo y la cubierta del suelo de cada ciudad y condado, y realizará ajustes para confirmar que los datos de los mapas de alta resolución coincidan con los datos a escala local.

Los datos actualizados del uso del suelo y la cubierta del suelo se cargarán luego en el Modelo de la Cuenca de la Bahía de Chesapeake, un modelo de computadora que se encuentra actualmente en el nivel 3 de sus 4 versiones de pruebas beta de producción y revisión. Las contrapartes estatales y municipales, distritos de conservación y otras contrapartes de la cuenca han revisado cada versión y sugerido cambios en función de su experiencia de mitigación de aguas de tormenta, modernizaciones de tratamiento de aguas y otras BMP. Los datos detallarán, por ejemplo, el desarrollo de uso mixto, distintos usos del suelo agrícola para cultivos, alfalfa y pastura; y mediciones tales como la producción de fruta o verduras del suelo. Aquí es donde la conversión de la cubierta del suelo al uso del suelo es útil para ayudar a especificar las tasas de carga de contaminación.

“Queremos un proceso muy transparente”, dice Rich Batiuk de la EPA, director asociado de ciencia, análisis e implementación del Programa de la Bahía de Chesapeake, señalando que los datos combinados de la cubierta del suelo y el uso del suelo se podrán acceder en línea sin cargo. “Queremos miles de ojos sobre los datos de uso y cubierta del suelo. Queremos ayudar a las contrapartes estatales y locales con datos sobre cómo lidiar con bosques, llanuras de inundación, arroyos y ríos. Y queremos mejorar el producto para poder obtener un modelo de simulación de políticas de control de la contaminación en toda la cuenca”.

Ampliación del trabajo y otras aplicaciones

A medida que la tecnología se refina y es utilizada más ampliamente por las contrapartes de la cuenca, The Conservancy espera poder crear otros juegos de datos, ampliar el trabajo a otras aplicaciones, y realizar actualizaciones anuales o bianuales para que los mapas sean siempre un reflejo de las condiciones reales. “Estos datos son importantes como una línea de base, y veremos cuál es la mejor manera de evaluar los cambios que se producen con el tiempo”, dice Allenby.

Las contrapartes de la cuenca están discutiendo aplicaciones adicionales para los juegos de datos de un metro de resolución, desde actualizar los mapas de emergencia/911, a proteger especies en extinción, a desarrollar servidumbres y comprar suelo para organizaciones de conservación. Más allá de la Bahía de Chesapeake, el trazado de mapas de precisión podría ayudar a realizar proyectos a escala de continente. Es el símil para la conservación de la agricultura de precisión, que permite determinar, por ejemplo, dónde se podría aplicar un poco de fertilizante para maximizar el beneficio para las plantas. Cuando se combinan estos dos elementos, la producción de alimentos puede crecer y reducir al mismo tiempo el impacto medioambiental de la agricultura. La tecnología también podría ayudar con prácticas de desarrollo más sostenible, el aumento del nivel del mar, y la resiliencia.

Mucha gente creyó que una pequeña organización sin fines de lucro no podía encarar este tipo de análisis, dice Allenby, pero su equipo pudo hacerlo por un décimo del costo estimado. El próximo paso sería poner estos datos del uso del suelo y la cubierta del suelo a disposición del público sin cargo. Pero en este momento eso sería muy oneroso. Los datos necesitan copias de respaldo, seguridad y una enorme cantidad de espacio de almacenamiento. El equipo de The Conservancy está transfiriendo los datos en colaboración con Esri, una compañía de Redlands, California, que vende herramientas de trazado de mapas por SIG, y también Microsoft Research y Hexagon Geospatial. El proceso se ejecuta en forma lineal, un metro cuadrado por vez. En un sistema que se ejecuta en la nube, se puede procesar un kilómetro cuadrado por vez y distribuir a 1.000 servidores por vez. Según Allenby, ello permitiría hacer un mapa a nivel de parcela de los 8,8 millones de kilómetros cuadrados de los EE.UU. en un mes. Sin esta tecnología, 100 personas tendrían que trabajar durante más de un año, a un costo mucho mayor, para producir el mismo juego de datos.

Los mapas de precisión podrían aportar mucho más detalle a State of the Nation’s Land, un periódico anual en línea de bases de datos sobre el uso y la propiedad del suelo que el Instituto Lincoln está produciendo con PolicyMap. McCarthy sugiere que la tecnología podría responder a preguntas tales como: ¿Quién es el dueño de los Estados Unidos? ¿Cómo estamos usando el suelo? ¿Cómo afecta la propiedad el uso del suelo? ¿Cómo está cambiando con el tiempo? ¿Cuál es el impacto de los caminos desde el punto de vista ambiental, económico y social? ¿Qué cosas cambian después de construir un camino? ¿Cuánto suelo rico para la agricultura ha estado enterrado debajo de los emprendimientos suburbanos? ¿Cuándo comienza a tener importancia? ¿Cuánto suelo estamos despojando? ¿Qué pasa con nuestro suministro de agua?

“¿Puede resolver problemas sociales grandes?”, pregunta McCarthy. Una de las consecuencias más importantes de la tecnología de mapas de precisión sería encontrar mejores maneras de tomar decisiones sobre las prácticas del uso del suelo, dice, sobre todo en la interfaz entre la gente y el suelo, y entre el agua y el suelo. Se necesitan los registros de suelo para usar esta tecnología más eficazmente, lo cual podría presentar un desafío en algunos lugares porque no hay registros, o los que hay no son sistemáticos. Pero es una metodología y tecnología que se puede usar en otros países, dice. “Es un cambio en las reglas del juego, permitiéndonos superponer datos del uso del suelo con datos de la cobertura del suelo, lo cual puede ser increíblemente valioso para lugares de urbanización rápida, como China y África, donde los patrones y cambios se podrán observar sobre el suelo y con el correr del tiempo. Es difícil exagerar su impacto”.

“Nuestro objetivo es usar esta tecnología para aumentar la transparencia y la rendición de cuentas en todo el mundo”, dice McCarthy. “Cuanto más información puedan acceder los planificadores, mejor podrán defender nuestro planeta”. La herramienta se debería compartir con la “gente que quiere usarla con el fin apropiado, de manera que estamos haciendo la propuesta de valor de que este es un bien público que todos debemos mantener”, dice, en forma similar a cómo USGS desarrolló el sistema SIG.

“Necesitamos la alianza pública-privada apropiada, algo así como un servicio público regulado, con supervisión y respaldo público, que se mantenga como un bien público”.

Kathleen McCormick, fundadora de Fountainhead Communications, LLC, vive y trabaja en Boulder, Colorado, y escribe frecuentemente sobre comunidades sostenibles, saludables y resilientes.

Crédito: The Chesapeake Conservancy

El reajuste de suelo es un proceso vital pero difícil y prolongado: es una especie de versión retroactiva de planificación de barrios que se desarrollaron informalmente, con viviendas no autorizadas construidas en forma caótica que no dejan espacio para el acceso a calles y pasajes. Según ONU-Hábitat, 863 millones de personas en el mundo vivían en este tipo de asentamientos en 2014, y esta cantidad podría ascender a 3.000 millones para 2050. El borrador acordado de la Nueva agenda urbana para la conferencia Hábitat III en Quito, Ecuador, señala que “la creciente cantidad de moradores de asentamientos precarios e informales” contribuye a los problemas que exacerban la pobreza global y sus riesgos concomitantes, desde la falta de servicios municipales a una mayor amenaza para la salud.

Pero la evolución tecnológica podría facilitar la revisión de esta disposición orgánica reduciendo el desplazamiento al mínimo y acelerando la absorción de estos barrios en la estructura formal de la ciudad, proporcionando así a los residentes servicios básicos, desde sistemas de alcantarillado y drenaje a acceso en caso de emergencia médica o de incendio. Una de las herramientas más prometedoras es Open Reblock, una plataforma que se encuentra actualmente en su fase piloto alrededor de Ciudad del Cabo, Sudáfrica y Mumbai, India. El proyecto nació de una colaboración entre Shack/Slum Dwellers International (SDI, que trabaja directamente con una red de comunidades urbanas pobres en 33 países), el Instituto Santa Fe (SFI, una organización sin fines de lucro de investigación y educación) y la Universidad Estatal de Arizona.

SDI se ha involucrado desde hace tiempo en el “retrazado” de base, esencialmente otra manera de caracterizar el proceso de reajuste de suelo. Luis Bettencourt, un profesor de sistemas complejos en el Instituto Santa Fe, explica que su grupo, que se enfoca en las “ciudades como sistemas”, comenzó a trabajar con SDI hace algunos años. Se produjo una convergencia útil del pensamiento de alto nivel basado en estadísticas y datos del grupo de SFI con los “relevamientos” utilizados por SDI sobre el terreno para trabajar con las comunidades de asentamientos informales.

Los esfuerzos de retrazado de asentamientos de SDI se realizan con mucho cuidado. Los residentes participaron en forma directa en el proceso de diagramación del barrio, usando papel y lápiz. Después se reunieron en juntas comunitarias, usando modelos de papel de cada estructura local colocados sobre el mapa, y comenzaron a reubicarlos para hacer lugar a nuevos pasajes y calles. Si bien esta colaboración activa fue profundamente beneficiosa, se puede decir que esta metodología analógica no se caracterizó por su rapidez.

En años recientes, la tecnología digital cada vez más accesible facilitó este proceso, dijo la secretaria de SDI, Anni Beukes. El grupo usa ahora una herramienta de sistema de información geográfica (SIG) para delinear el mapa del barrio y los servicios básicos disponibles, y después usa una herramienta separada para realizar relevamientos más detallados a nivel de hogar y medidas precisas de cada estructura. Dada la amplia disponibilidad de teléfonos móviles y tabletas, el proceso es abierto y depende, en efecto, de la participación directa de los residentes.

Enrique R. Silva, un becario de investigación y asociado sénior de investigación en el Instituto Lincoln de Políticas de Suelo, señala que se están usando herramientas de relevamiento similares alrededor del mundo. “Uno puede hacer un mapa de algo en forma casi instantánea”, dice, y los miembros de la comunidad participan en este proceso. Apunta a los esfuerzos, con respaldo del Instituto Lincoln y otros, que utilizan dispositivos “baratos y universales” y herramientas de crowd-sourcing para alcanzar metas similares en América Latina.

Un mapa maestro disponible en forma digital también crea nuevas posibilidades. Un ejemplo es Open Reblock. Utiliza un algoritmo exclusivo para leer un mapa digital de un asentamiento informal y proponer la estrategia que, desde su punto de vista, es óptima para rediseñarlo. (El algoritmo está escrito para priorizar las calles y estructuras existentes, haciéndose eco del objetivo tradicional de minimizar el desplazamiento.) Este proceso sólo toma unos minutos, cuanto mucho.

“Cuando se lo mostré por primera vez a nuestras comunidades, se quejaron de que les estaba sacando los modelos hechos en papel”, dice Beukes, riéndose. No estaban equivocados . . . pero no estaban realmente protestando.

Pero lo que produce Open Reblock no tiene como objetivo ser una directiva estricta o una propuesta final. Los miembros de la comunidad pueden ajustar los resultados basados en su conocimiento directo y sus preocupaciones. Es más, Open Reblock depende de dicha participación, creando una realidad compartida donde la gente puede jugar y crear su futura realidad, dice Bettencourt. “Es básicamente una herramienta de planificación municipal, a nivel de un barrio”. Al ofrecer una “prueba de demostración y un punto inicial” para las negociaciones, agrega, y acelera radicalmente uno de los pasos más difíciles del proceso.

Beukes dice que los participantes en los programas piloto han reaccionado con entusiasmo ante las nuevas posibilidades de este sistema. Entre otros factores: También significa que un plan final tendrá una forma más adecuada, para que funcionarios municipales puedan responder más fácilmente, y asegura que todas las partes estén viendo (y debatiendo) los mismos datos geoespaciales y esquemas de planificación. “Es una plantilla para iniciar la discusión”, agrega Bettencourt, “donde literalmente todos están mirando el mismo mapa”.

Gracias a una subvención de Open Ideo, el equipo de Bettencourt y SDI están trabajando para mejorar el diseño de la interfaz de Open Reblock, aprovechando las observaciones de los participantes comunitarios de Cabo de Hornos y Mumbai. Todo el proyecto está siendo creado con código abierto (disponible en Github), tanto para alentar mejoras por parte de cualquier persona que se quiera involucrar como para facilitar versiones más completas para uso más masivo y universal en el futuro.

Por supuesto, el proyecto no es una solución mágica. Los reajustes de suelo pueden ser contenciosos, y Silva apunta que todavía se tienen que resolver temas importantes sobre el valor de la propiedad de cada morador a un nivel más individual y humano. Bettencourt y Beukes están de acuerdo en que Open Reblock es un suplemento y no un sustituto de los procesos existentes.

De todas maneras, Bettencourt apunta a las cifras de ONU-Hábitat para especular que puede haber un millón de barrios alrededor del mundo que necesitan un retrazado. “Es un número increíble”, dice. Y confirma la opinión de los observadores de que este esfuerzo es algo casi imposible, sobre todo cuando el proceso se va prolongando con cada caso individual.

Pero desde la perspectiva de un tecnólogo, esto puede ser menos intimidatorio. Basta con pensar en las herramientas de confección de mapas y recolección de datos que han emergido en años recientes, como un paso inicial que extiende el trabajo de larga data de SDI y otros. Open Reblock es simplemente una iteración más en esa trayectoria. “Creo que tenemos todos los ingredientes, pero tenemos que empezar a ejecutar”, dice Bettencourt. “Si además contamos con un sistema para capturar datos y generar propuestas, esto es un gran paso adelante. No genera el cambio, pero ayuda”.

Rob Walker (robwalker.net) es contribuyente de Design Observer y The New York Times.

Folleto | Datos del mapa © OpenStreetMap contribuyentes, CC-BY-SA, Imagery © Mapbo

Durante años, pareció que el próximo adelanto importante en cuanto al transporte público en la ciudad suburbana de Altamonte Springs, Florida, sería un programa innovador denominado FlexBus. En lugar de recorrer rutas fijas, estos autobuses responderían a las demandas de los kioscos ubicados en centros de actividad específicos. Este sistema era, en palabras del administrador municipal Frank Martz, “el primer proyecto de transporte a demanda desarrollado en los Estados Unidos”. Algunos incluso se referían a este sistema como “el Uber para el tránsito”.

Lamentablemente, no funcionó. El operador regional de autobuses que gestionaba el proyecto perdió el financiamiento federal clave que requería el sistema, por lo que Altamonte Springs tuvo que buscar una nueva solución. Tal como expresa Martz, “en lugar de enojarnos, decidimos resolver el problema, ya que todavía teníamos que brindarles un servicio a nuestros residentes”.

Esta vez, los funcionarios se decidieron por Uber. La primavera pasada, el suburbio de Orlando anunció que se asociaría directamente con la firma de transporte compartido y subsidiaría a los ciudadanos que optaran por usar dicho servicio en lugar de sus propios automóviles, especialmente para viajes hacia las estaciones de ferrocarril regionales que conectan a los centros de población alrededor del condado de Seminole. Este programa piloto ha tenido una aceptación popular lo suficientemente buena, por lo que otros municipios dentro del área ya han lanzado programas similares.

Casi todo lo que oímos acerca de la relación entre los municipios y los emprendimientos de transporte compartido implica contiendas. Para la época en que Altamonte Springs comenzó su programa piloto, un enfrentamiento sobre detalles normativos en Austin, Texas, dio como resultado que Uber y su principal competencia, Lyft, dejaron de prestar servicios en esa ciudad. Sin embargo, Altamonte Springs es un ejemplo de cómo algunas ciudades, planificadores y académicos están intentando encontrar oportunidades dentro de la creciente importancia y popularidad del transporte compartido. El Laboratorio Senseable City del MIT ha trabajado con Uber; y el Centro de Investigación para la Sostenibilidad del Transporte de la Universidad de California en Berkeley y otras instituciones han estado estudiando los datos relacionados con el transporte compartido, con un enfoque en sus efectos sobre el transporte público. Además, el pasado marzo, la Asociación de Transporte Público de los Estados Unidos divulgó un estudio en el que se evaluaba la manera en que los nuevos servicios pueden ser un complemento a las formas más familiares de “movilidad compartida”, y se sugerían diferentes formas en que las agencias podían “promover una cooperación útil entre los proveedores de transporte público y privado”.

“Todo se reduce a la forma en que el nuevo sistema interactúa con el sistema tradicional existente”, opina Daniel Rodríguez, fellow del Instituto Lincoln y profesor de planificación en la Universidad de Carolina del Norte, quien además ha estudiado las innovaciones en el transporte en América Latina y los Estados Unidos. Rodríguez espera que surjan aun más experimentos a medida que las ciudades hacen todo lo posible para ver cómo “los usuarios de Uber pueden complementar la infraestructura existente”.

Y esto describe casi en su totalidad una de las primeras motivaciones del programa piloto de Uber en Altamonte Springs: el servicio, según Martz, era una opción que ya existía y que no requería ninguno de los compromisos de tiempo y dinero asociados a una iniciativa de transporte típica. “El enfoque no podía ni debía ponerse en la infraestructura”, observa Martz. “Debíamos centrarnos en el comportamiento humano”. En otras palabras, los servicios de transporte compartido ya responden a la demanda que el mercado demuestra tener; entonces ¿cómo podría la ciudad aprovechar dicha tendencia?

La respuesta fue ofrecer un subsidio a los usuarios del municipio: la ciudad pagaría el 20 por ciento del costo de cualquier viaje dentro de la ciudad, y el 25 por ciento del costo de cualquier viaje desde o hacia las estaciones de Sun Rail, el sistema de ferrocarril suburbano de la región. Los usuarios sólo tienen que ingresar un código que funciona en conjunto con la tecnología geofencing (segmentación geográfica) de Uber para confirmar la elegibilidad geográfica, la tarifa se reduce según lo que corresponda, y el municipio continuamente cubre la diferencia. “Es un tema de conveniencia para el usuario”, indica Martz, aunque hace hincapié en un tema más importante que la facilidad de pago. En lugar de crear sistemas a los que los ciudadanos respondan, tal vez sea mejor intentar un sistema que responda a los ciudadanos en donde se encuentran, y que se adapte en tiempo real a medida que cambian de lugar.

Queda por ver si este sistema funcionará a largo plazo, pero, como experimento, los riesgos son bastante bajos. Martz ha estimado un costo anual para el municipio de aproximadamente US$100.000 (el costo del proyecto anterior del FlexBus era de US$1.500.000). Aunque el plan piloto sólo lleva unos pocos meses en marcha, Martz observa que, a nivel del municipio, Uber se utiliza diez veces más que antes, razón por la cual otros municipios vecinos, tales como Longwood, Lake Mary, Sanford y Maitland, se han sumado al proyecto o han anunciado sus planes para hacerlo. “Estamos creando un grupo de trabajo entre nuestras ciudades”, agrega Martz, con el objetivo de gestionar la congestión del tránsito y ver “cómo conectar nuestras ciudades”.

Tal como lo indica Rodríguez, sólo las implicaciones en cuanto al uso del suelo, tanto a corto como a largo plazo, son convincentes de por sí. En cuanto al día a día, la posibilidad de tener un transporte compartido económico para, por ejemplo, ir al médico, acudir a reuniones en la escuela o realizar trámites similares reduce la demanda de espacios de estacionamiento. A un nivel más amplio, este sistema aprovecha las opciones que ya existen, en lugar de tener que diseñar proyectos con un uso más intensivo del suelo que pueden llevar años de planificación e implementación.

En un sentido, el experimento se encuadra dentro de una tendencia mucho más amplia de buscar innovaciones de transporte específicas. Rodríguez ha estudiado varios experimentos, desde sistemas de autobús ideados en forma local hasta tranvías por encima del nivel del suelo en América Latina que complementaban los sistemas existentes, en lugar de construir sistemas nuevos. Rodríguez señala además que, aunque, a primera vista, el concepto de asociarse con un servicio de transporte compartido pueda parecer que funciona solo en municipios pequeños que carecen de un sistema realista de tránsito masivo, este proyecto podría funcionar realmente bien en ciudades más grandes. Por ejemplo, tenemos el caso de São Paulo, Brasil, que ofrece lo que el suplemento CityLab de la revista The Atlantic ha dado en llamar “el mejor plan que existe para tratar con Uber”: en esencia, subastar créditos, disponibles tanto para los servicios de taxi existentes como para los emprendimientos de transporte compartido, para realizar viajes por una cantidad específica de kilómetros en un tiempo determinado. Los detalles normativos (diseñados, en parte, por Ciro Biderman, ex fellow del Instituto Lincoln) tienen por fin brindarle opciones a la ciudad, a la vez que atraen y explotan la demanda del mercado, en lugar de intentar darle forma.

Esta idea se condice con la postura amplia de Martz, quien se pregunta, “¿Por qué el sector público debe enfocarse en una infraestructura que era aceptada por los usuarios de hace 40 años?” Aunque de inmediato observa que esta forma de pensamiento en cuanto a las políticas se encuentra alineada en gran medida con las posturas que promueven los libres emprendimientos en un “condado muy republicano”, Martz también insiste en que el apoyo político municipal al plan ha cruzado los límites partidarios. Y lo que resulta más significativo es que esta solución, según Martz, permite que la ciudad se adapte mucho más fácilmente a los cambios tecnológicos que se van dando. La opción de compartir el vehículo parece ser una posibilidad lógica, y se sabe que Uber y otras empresas tecnológicas están barajando la posibilidad de utilizar vehículos sin conductor, que podrían incluso ser más eficientes. Martz no lo expresa abiertamente, pero si Uber se ve “afectado” por una solución más eficiente, asociarse con una firma nueva sería mucho más fácil que rehacer un proyecto de varios años en toda la región. “Dejemos que ganen las fuerzas del mercado”, sugiere Martz.

Por supuesto que, tal como indica Rodríguez, todo este sistema se encuentra aún en una etapa muy experimental, y la aceptación total de un sistema de transporte compartido puede también traer efectos negativos: obviamente el sistema se centra en los automóviles, por lo que no es necesariamente económico para un amplio sector de la población en muchas ciudades, incluso teniendo en cuenta el 20 por ciento de descuento. Además, la posibilidad de viajar mayores distancias a un costo más bajo ha sido uno de los factores principales de la expansión urbana descontrolada. “Esto podría representar un paso más en esa dirección”, observa Rodríguez.

Sin embargo, esta combinación de incertidumbres y posibilidades es exactamente la razón por la que vale la pena ocuparse de medidas que acepten a los emprendimientos de transporte compartido en lugar de enfrentarse a los mismos. “Por el momento, no existe una respuesta correcta; todavía estamos investigando el tema”, advierte Rodríguez. Aun así, los sistemas como Uber de hecho ofrecen un atributo que aquellos que desean experimentar cosas nuevas no pueden negar: “Es tangible, y se sabe que funciona”, concluye Rodríguez.

Rob Walker (robwalker.net) es colaborador de Design Observer y The New York Times.

En su ensayo de 1937, “¿Qué es una ciudad?”, Lewis Mumford describió un proceso evolutivo mediante el cual la “ciudad populosa mal organizada” evolucionaría hasta alcanzar un nuevo tipo de ciudad “de núcleos múltiples, con espacios y límites adecuados”:

“Veinte de estas ciudades, en una región cuyo entorno y recursos fueran planificados adecuadamente, tendrían todos los beneficios de una metrópolis de un millón de personas, pero sin sus grandes desventajas, tales como un capital congelado en servicios públicos no rentables o valores del suelo congelados a niveles que entorpecen la adaptación efectiva a nuevas necesidades”.

Para Mumford, cada una de estas ciudades, diseñadas mediante una sólida participación pública, se convertiría en un núcleo dentro de nuevas regiones metropolitanas de núcleos múltiples que darían como resultado lo siguiente:

“Una vida más integral para la región, ya que esta área geográfica puede sólo ahora y por primera vez ser considerada como un todo instantáneo respecto de todas las funciones de la existencia social. En lugar de depender de la mera masificación de las poblaciones para producir la concentración social y la adaptación social necesarias, debemos ahora procurar estos resultados a través de una nucleación municipal deliberada y una articulación regional más ajustada”.

Lamentablemente, desde que Mumford escribió estas palabras no hemos logrado establecer ciudades o regiones de núcleos múltiples ni hemos avanzado en la teoría de la evolución urbana. Los teóricos en temas urbanos se han abocado a describir a las ciudades, utilizar sistemas de reconocimiento de patrones básicos para detectar las relaciones entre los posibles componentes de la evolución urbana, u ofrecer prescripciones limitadas para resolver un problema urbano específico a la vez que se generan inevitables consecuencias involuntarias que representan nuevos desafíos. Y todo esto porque nunca hemos desarrollado una verdadera ciencia de las ciudades.

Durante más de un siglo, tanto planificadores como sociólogos, historiadores y economistas han teorizado sobre las ciudades y su evolución utilizando categorías, tal como indica Laura Bliss en un artículo de CityLab bien documentado del año 2014, el cual versa sobre la posibilidad de que surja una teoría evolutiva de las ciudades. Estos académicos generaron muchas tipologías de ciudades, desde clasificaciones funcionales hasta taxonomías rudimentarias (ver Harris, 1943, Functional Classification of Cities in the United StatesAtlas of Urban ExpansionAtlas of Cities). Sin embargo, el fundamento de estas clasificaciones eran categorías elegidas arbitrariamente, por lo que no aportaron mucho a nuestra comprensión de la forma en que las ciudades llegaron a ser lo que son hoy ni se animaron a presagiar lo que podrían llegar a ser.

Incluso Jane Jacobs, en el prefacio de su libro The Death and Life of Great American Cities (La vida y la muerte de las grandes ciudades de los Estados Unidos) de 1961, hace un llamado al desarrollo de una ecología de las ciudades –es decir, la exploración científica de las fuerzas que dan forma a las ciudades– pero se limita a brindar informes sobre cuáles son los factores que definen a una gran ciudad, en su mayoría en cuanto al diseño, como parte del ataque continuo de la autora hacia los planificadores ortodoxos. En algunos de sus trabajos posteriores, Jacobs establece principios para definir a las grandes ciudades, que se centran principalmente en la forma, aunque no brinda un marco para mejorar la ciencia de la teoría urbana.

La teoría urbana moderna está plagada de varios defectos: no es analítica; no logra brindar un marco para generar hipótesis y un análisis empírico para probar dichas teorías; y la investigación, en general, se centra en grandes ciudades icónicas, en lugar de extraer una selección representativa mundial de asentamientos urbanos que muestre las diferencias entre las ciudades pequeñas y las grandes, las ciudades principales y las secundarias, las ciudades industriales y las comerciales. Y lo que resulta más importante, la investigación no proporciona mucha orientación sobre cómo deberíamos intervenir para mejorar nuestras ciudades futuras con el fin de apoyar a los asentamientos humanos sostenibles en nuestro planeta.

La Nueva Agenda Urbana, que se anunciará en la III Conferencia de ONU-Habitat, a realizarse en el mes de octubre en Quito, Ecuador, presen–tará objetivos mundiales consensuados para la urbanización sostenible. Estos objetivos brindan una orientación a los estados miembro de las Naciones Unidas a medida que se preparan para la colosal tarea de dar la bienvenida a 2,5 mil millones de nuevos ciudadanos urbanos a las ciudades del mundo en los próximos treinta años, lo que concluirá el proceso de 250 años mediante el cual los asentamientos humanos pasaron de ser casi en su totalidad rurales y agrarios a ser predominantemente urbanos. No obstante, antes de intentar siquiera implementar la Nueva Agenda Urbana, debemos confrontar las graves limitaciones que tenemos en nuestra comprensión de las ciudades y de la evolución urbana. Una nueva “ciencia de las ciudades” reforzaría nuestros intentos por lograr que esta última etapa de la urbanización funcione correctamente.

Mi intención en este mensaje no es presentar una nueva ciencia de las ciudades, sino sugerir una forma de darle un marco a esta ciencia con base en la teoría evolutiva. La evolución de las especies se encuentra determinada por cuatro fuerzas principales, por lo que parece razonable que estas mismas fuerzas ayuden a dar forma a la evolución de las ciudades. Estas fuerzas son: la selección natural, la migración genética, la mutación y la deriva aleatoria, las cuales se van dando en formas predecibles para dar forma a las ciudades, de tal manera que, en lugar del concepto de “éxito reproductivo” tenemos el concepto de “crecimiento de la ciudad” como indicador del éxito evolutivo.

La selección natural es un proceso de impulso y respuesta, que está relacionado con la forma en que una ciudad responde a los factores de cambio externos (impulsos) que fomentan o inhiben el éxito. Los impulsos pueden ser económicos, medioambientales o políticos, pero lo que más debe destacarse es que están fuera del control de la ciudad. Por ejemplo, la reestructuración económica puede generar una selección en detrimento de las ciudades que dependen de la manufactura, tienen una mano de obra capacitada en forma inflexible o extraen o producen bienes de consumo simples con una demanda cambiante en los mercados mundiales. El cambio climático y el aumento del nivel del mar pueden inhibir el éxito de las ciudades costeras o aquellas expuestas a graves catástrofes climatológicas. Los impulsos políticos pueden consistir en cambios de régimen, revueltas sociales o guerras, o pueden ser situaciones en apariencia de menor importancia, tales como un cambio en la fórmula de distribución respecto de los ingresos a nivel nacional. Cada impulso beneficiará a unas ciudades y traerá perjuicios a otras. La capacidad de una ciudad para responder a los diferentes impulsos puede tomarse como una medida de su nivel de resiliencia, la cual se ve directamente afectada por las otras tres fuerzas evolutivas.

La migración genética (o flujo genético) ayuda a diversificar las estructuras económicas, sociales y etarias de las ciudades a través del intercambio de individuos, recursos y tecnologías. Supuestamente, la inmigración de individuos, capital y nueva tecnología mejora la capacidad de una ciudad para responder a los impulsos externos. Por otro lado, la emigración, en general, reduciría dicha capacidad.

Para las ciudades, la mutación consiste en un cambio impredecible en la tecnología o en la práctica que ocurre dentro de una ciudad, y puede consistir tanto en una innovación como en una interrupción.

La deriva aleatoria implica cambios en las ciudades a largo plazo, los cuales son el resultado de cambios culturales o de comportamiento. Aquí podemos mencionar a las decisiones que se toman para mantener o preservar los bienes de largo plazo, ya sean inmuebles o bienes culturales. La deriva describe las formas impredecibles en que las ciudades pueden modificar su carácter.

Como ya lo he mencionado, no es mi intención establecer aquí una nueva teoría de evolución urbana. Sólo recomiendo tomar esta dirección a fin de estimular nuestro pensamiento en torno al cambio urbano de forma más rigurosa y sistemática. Ya se ha dedicado una gran cantidad de trabajo a cuantificar los elementos que forman parte de este marco. Los teóricos especializados en riesgos y las aseguradoras han cuantificado muchos de los impulsos externos que presentan desafíos a las ciudades. Los demógrafos y los teóricos especializados en poblaciones han estudiado la migración humana, y los macroeconomistas han estudiado los flujos de capital. Se ha prestado mucha atención a la innovación y a las interrupciones en las últimas décadas. La deriva aleatoria no se ha estudiado mucho. Sin embargo, tal como observa Bliss, la gran cantidad de datos y las nuevas tecnologías pueden ayudarnos a detectar la deriva a largo plazo. De todas maneras, un marco de mayores proporciones en el que se entretejan todas estas áreas de estudio tan diferentes podría ayudarnos a comprender más la evolución urbana.

No obstante, aunque una teoría evolutiva de las ciudades representaría un avance evidente en cuanto a la teoría urbana, debo advertir aquí que, a diferencia de lo que ocurre con la evolución, que es un proceso mayoritariamente pasivo –las especies soportan las fuerzas externas que actúan sobre ellas– las ciudades, al menos en teoría, se ven impulsadas por un comportamiento más intencional: la planificación. Sin embargo, los planificadores necesitan mejores herramientas para ejercer sus tareas y probar sus enfoques. Si queremos implementar con éxito la Nueva Agenda Urbana, sería muy útil contar con un conjunto de herramientas basadas en la ciencia evolutiva. Finalmente, Mumford concluye su ensayo de 1937 de la siguiente manera:

“La tarea de la próxima generación consiste en materializar todas estas nuevas posibilidades en la vida de la ciudad, lo cual se puede lograr no simplemente a través de una mejor organización técnica sino mediante una comprensión sociológica más acabada, y adaptar las actividades propiamente dichas a individuos y estructuras urbanas adecuadas”.

En el Instituto Lincoln de Políticas de Suelo estamos listos para apoyar a las próximas generaciones al realizar un análisis integral y científico de la evolución urbana y del importante rol que las políticas de suelo efectivas pueden representar a la hora de impulsar dicha evolución. Nuestro futuro urbano depende de ello.

The Chesapeake Bay is a cultural icon, a national treasure, and a natural resource protected by hundreds of agencies, nonprofit organizations, and institutions. Now with unprecedented accuracy, a new ultra-high-resolution digital mapping technology, developed by the Chesapeake Conservancy and supported by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, is pinpointing pollution and other threats to the ecosystem health of the bay and its watershed, which spans 64,000 square miles, 10,000 miles of shoreline, and 150 major rivers and streams. At one-meter-by-one-meter resolution, the “precision conservation” mapping technology is gaining the attention of a wide range of agencies and institutions that see potential applications for a variety of planning purposes, for use throughout the United States and the world. This new land cover dataset, created by the Conservancy’s Conservation Innovation Center (CIC), has 900 times more information than previous datasets, and provides vastly greater detail about the watershed’s natural systems and environmental threats—the most persistent and pressing of which is pollution of the bay’s waters, which impacts everything from the health of people, plants, and wildlife to the fishing industry to tourism and recreation.

“The U.S. government is putting more than $70 million a year into cleaning up the Chesapeake but doesn’t know which interventions are making a difference,” says George W. McCarthy, president and CEO of the Lincoln Institute. “With this technology, we can determine whether interventions can interrupt a surface flow of nutrients that is causing algae blooms in the bay. We can see where the flows enter the Chesapeake. We’ll see what we’re getting for our money, and we can start to redirect the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Department of Agriculture, and multiple agencies that might plan strategically but not talk to each other.”

The nonprofit Chesapeake Conservancy is putting finishing touches on a high-resolution map of the entire watershed for the Chesapeake Bay Program. Both organizations are located in Annapolis, Maryland, the epicenter of bay conservation efforts. The program serves the Chesapeake Bay Partnership, the EPA, the Chesapeake Bay Commission, and the six watershed states of Delaware, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia—along with 90 other partners including nonprofit organizations, academic institutions, and government agencies such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Geologic Survey (USGS), and the U.S. Department of Defense.

On behalf of this partnership, EPA in 2016 invested $1.3 million in state and federal funding in the Conservancy’s high-resolution land cover project, which is being developed with the University of Vermont. Information gleaned from several precision mapping pilot programs is already helping local governments and river partners make more efficient and cost-effective land-management decisions.

“There are a lot of actors in the Chesapeake Bay watershed,” says Joel Dunn, president and CEO of the Chesapeake Conservancy. “We’ve been working on a very complicated conservation problem as a community over the last 40 years, and the result has been layers and layers and many institutions built to solve this problem.”

“Now it’s not a collective will problem but an action problem, and the whole community needs to be partnering in more innovative ways to take restoration of the watershed’s natural resources to the next level,” he adds.

“Conservation technology is evolving quickly and may be cresting now,” Dunn says, “and we want to ride that wave.” The project is an example of the Conservancy’s efforts to take its work to new heights. By bringing “big data” into the world of environmental planning, he says, the Conservancy is poised to further innovate as “conservation entrepreneurs.”

What Is Precision Mapping Technology?

Land use and land cover (LULC) data from images taken by satellites or airplanes is critical to environmental management. It is used for everything from ecological habitat mapping to tracking development trends. The industry standard is the USGS’s 30-by-30-meter-resolution National Land Cover Database (NLCD), which provides images encompassing 900 square meters, or almost one-quarter acre. This scale works well for large swaths of land. It is not accurate, however, at a small-project scale, because everything at one-quarter acre or less is lumped together into one type of land classification. A parcel might be classified as a forest, for example, when that quarter-acre might contain a stream and wetlands as well. To maximize improvements to water quality and critical habitats, higher resolution imaging is needed to inform field-scale decisions about where to concentrate efforts.

Using publicly available aerial imagery from the National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP), combined with LIDAR (or Light Detection and Ranging) land elevation data, the Conservancy has created three-dimensional land classification datasets with 900 times more information and close to a 90 percent accuracy level, compared to a 78 percent accuracy level for the NLCD. This new tool provides a much more detailed picture of what’s happening on the ground by showing points where pollution is entering streams and rivers, the height of slopes, and the effectiveness of best management practices (BMPs) such as bioswales, rain gardens, and forested buffers.

“We’re able to translate raw imagery to a classified landscape, and we’re training the computer to look at what humans see at eye level,” and even to identify individual plants, says Jeff Allenby, director of conservation technology, who was hired in 2012 to leverage technology to study, conserve, and restore the watershed. In 2013, a $25,000 grant from the Information Technology Industry Council (ITIC) allowed Allenby to buy two powerful computers and begin working on the digital map. With support from the Chesapeake Bay Program, his geographic information system (GIS)-savvy team of eight has created a classification system for the Chesapeake watershed with 12 categories of land cover, including impervious surfaces, wetlands, low vegetation, and water. It is also incorporating zoning information about land uses from the Chesapeake Bay Program.

The Technology’s Potential

Precision mapping “has the potential to transform the way we look at and analyze land and water systems in the United States,” says James N. Levitt, manager of land conservation programs for the department of planning and urban form at the Lincoln Institute, which is supporting the Conservancy’s development of the technology with $50,000. “It will help us maintain water quality and critical habitats, and locate the areas where restoration activities will have the greatest impact on improving water quality.” Levitt says the technology enables transferring “nonpoint,” or diffuse and undetermined, sources of pollution into specific identifiable “point” sources on the landscape. And it offers great potential for use in other watersheds, such as the Ohio and Mississippi river systems, which, like the Chesapeake watershed, also have large loads of polluted stormwater runoff from agriculture.

It’s a propitious time to be ramping up conservation technology in the Chesapeake region. In February 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court decided not to consider a challenge to the Chesapeake Bay Partnership’s plan to fully restore the bay and its tidal rivers as swimmable and fishable waterways by 2025. The high court’s action let stand a ruling by the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals that upheld the clean water plan and reinforced restrictions on the total maximum daily load, or the permissible limit of pollution from substances like nitrogen and phosphorus. These nutrients, found in agricultural fertilizers, are the two major pollutants of the bay, and are addressed under federal water quality standards established by the Clean Water Act. The ruling also allows EPA and state agencies to fine polluters for violating regulations.

The Chesapeake Bay’s water quality has improved from its most polluted phase in the 1980s. Upgrades and more efficient operations at wastewater treatment plants have reduced nitrogen going into the bay by 57 percent and phosphorus by 75 percent. But the watershed states are still in violation of clean water regulations, and increasing urban development calls for constant assessment and pollution reduction in water and critical habitats.

Pilot Project No. 1: Chester River

Backed by funding from ITIC’s Digital Energy and Sustainability Solutions Campaigns, the Conservancy completed a high-resolution land classification and stormwater runoff flow analysis for the entire Chester River watershed on Maryland’s eastern shore. Isabel Hardesty is the river keeper for the 60-mile-long Chester River and works with the Chester River Association, based in Chestertown, Maryland. (“River keeper” is an official title for 250 individuals worldwide who serve as the “eyes, ears, and voice” for a body of water.) The Conservancy’s analysis helped Hardesty and her staff understand where water flows across the land, where BMPs would be most effective, and which degraded streams would be best to restore.

Two-thirds of the Chester River watershed’s land cover is row crops. Row-crop farmers often apply fertilizer uniformly to a field, and the fertilizer runs off with stormwater from all over the site. This is considered nonpoint pollution, which makes it harder to pinpoint the exact source of contaminants flowing into a river—compared to, say, a pile of manure. The Conservancy’s team mapped the entire Chester watershed, noting where rain fell on the landscape and then where it flowed.

“With the naked eye, you can look at a field and see where the water is flowing, but their analysis is much more scientific,” says Hardesty. The map showed flow paths across the whole watershed, in red, yellow, and green. Red indicates higher potential for carrying pollutants, such as flow paths over impervious surfaces. Green means water is filtered, such as when it flows through a wetlands or a forested buffer, making it less likely to carry pollution. Yellow is intermediary, meaning it could go either way. The analysis has to be “ground-truthed,” says Hardesty, meaning the team uses the GIS analysis and drills down to an individual farm level to confirm what’s happening on a specific field.

“We are a small organization and have relationships with most of the farmers in the area,” says Hardesty. “We can look at a parcel of land, and we know the practices that farmers use. We’ve reached out to our landowners and worked with them on their sites and know where pollution may be entering streams. When we know a particular farmer wants to put a wetland on his farm, this land use and water flow analysis helps us determine what kind of BMP we should use and where it should be located.” The value of precision mapping for the Chester River Association, says Hardesty, has been “realizing that the best place to put a water intercept solution is where it’s best for the farmer. This is usually a fairly unproductive part of the farm.” She says farmers generally are happy to work with them to solve the problem.

The Chester River Association is also deploying the technology to use resources more strategically. The organization has a water monitoring program with years of watershed data, which the Conservancy team analyzed to rank streams according to water quality. The association now has GIS analysis that shows the flow paths for all stream subwatersheds, and is creating a strategic plan to guide future efforts for streams with the worst water quality.

Pilot Project No. 2: York County Stormwater Consortium BMP Reporting Tool

In 2013, the Conservancy and other core partners launched Envision the Susquehanna to improve the ecological and cultural integrity of the landscape and the quality of life along the Susquehanna River, from its headwaters in Cooperstown, New York, to where it merges with the Chesapeake Bay in Havre de Grace, Maryland. In 2015, the Conservancy selected the program to pilot its data project in York County, Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania has struggled to demonstrate progress in reducing nitrogen and sediment runoff, especially in places where urban stormwater enters rivers and streams. In 2015, EPA announced that it would withhold $2.9 million in federal funding until the state could articulate a plan to meet its targets. In response, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection released the Chesapeake Bay Restoration Strategy to increase funding for local stormwater projects, verify the impacts and benefits of local BMPs, and improve accounting and data collection to monitor their effectiveness.

York County created the York County–Chesapeake Bay Pollution Reduction Program to coordinate reporting on clean-up projects. The Conservancy’s precision mapping technology offered a perfect pilot opportunity: In spring 2015, the York County Planning Commission and the Conservancy began working together to improve the process for selecting BMP projects for urban stormwater runoff, which, combined with increased development, is the fastest growing threat to the Chesapeake Bay.

The planning commission targeted the annual BMP proposal process for the 49 of 72 municipalities that are regulated as “municipal separate storm sewer systems,” or MS4s. These are stormwater systems required by the federal Clean Water Act that collect polluted runoff that would otherwise make its way into local waterways. The commission’s goal was to standardize the project submittal and review processes. The county had found that calculated load reductions often were inconsistent among municipalities because many lacked the staff to collect and analyze the data or used a variety of different data sources. This made it difficult for the commission to identify, compare, and develop priorities for the most effective and cost-efficient projects to achieve water-quality goals.

How to Use the York County Stormwater Consortium BMP Reporting Tool

To use the online tool, users select a proposed project area, and the tool automatically generates a high-resolution land cover analysis for all of the land area draining through the project footprint. High-resolution data is integrated into the tool, allowing users to assess how their project would interact with the landscape. Users also can compare potential projects quickly and easily, and then review and submit proposals for projects with the best potential to improve water quality. Users then input their project information into a nutrient/sediment load reduction model called the Bay Facility Assessment Scenario Tool, or BayFAST. Users enter additional project information, and the tool fills in the geographic data. The result is a simple, one-page pdf report that outlines the estimated project costs per pound of nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment reduction. See the tool at: http://chesapeakeconservancy.org/apps/yorkdrainage/.

The Conservancy and planning commission collaborated to develop the user-friendly, web-based York County Stormwater Consortium BMP Reporting Tool (above), which allows different land use changes and restoration approaches to be compared and analyzed before being put into place. The Conservancy, commission, and municipal staff members collaborated on a uniform template for the proposals and data collection, and they streamlined the process with the same data sets. The Conservancy then trained a few of the local GIS professionals to provide technical assistance to other municipalities.

“It’s easy and quick to use,” explains Gary Milbrand, CFM, York Township’s GIS engineer and chief information officer, who is a project technical assistant for other municipalities. In the past, he says, municipalities typically spent between $500 and $1,000 on consultants to analyze their data and create proposals and reports. The reporting tool, he says, “saves us time and money.”

The commission required all regulated municipalities to submit BMP proposals using the new technology by July 1, 2016, and proposals will be selected for funding by late fall. Partners say the municipalities are more involved in the process of describing how their projects are working in the environment, and they hope to see more competitive projects in the future.

“For the first time, we can compare projects ‘apples to apples,’” says Carly Dean, Envision the Susquehanna project manager. “Just being able to visualize the data helps municipal staffs analyze how their projects interact with the landscape, and why their work is so important.” Dean adds, “We’re only just beginning to scratch the surface. It will take a while before we grasp all of the potential applications.”

Integrating Land Cover and Land Use Parcel Data

The Conservancy team is also working to overlay land cover data with parcel-level county data to provide more information on how land is being used. Combining high-resolution satellite imagery and county land use parcel data is unprecedented. Counties throughout the United States collect and maintain parcel-level databases with information such as tax records and property ownership. About 3,000 out of 3,200 counties have digitized these public records. But even in many of these counties, records haven’t been organized and standardized for public use, says McCarthy.

EPA and a USGS team in Annapolis have been combining the one-meter-resolution land cover data with land use data for the six Chesapeake states to provide a broad watershed-wide view that at the same time shows highly detailed information about developed and rural land. This fall, the team will incorporate every city and county’s land use and land cover data and determine adjustments to make sure the high-resolution map data matches local-scale data.

The updated land use and cover data then will be loaded into the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Model, a computer model now in its third of four beta versions of production and review. State and municipal partners, conservation districts, and other watershed partners have reviewed each version and suggested changes based on their experience in stormwater mitigation, water treatment upgrades, and other BMPs. Data will detail, for example, mixed-use development; different agricultural land uses for crops, hay, and pasture; and measures such as how much land produces fruit or vegetable crops. That’s where the conversion from land cover to land use comes in to help specify the pollution load rates.

“We want a very transparent process,” says EPA’s Rich Batiuk, associate director for science, analysis, and implementation for the Chesapeake Bay Program, noting that the combined land cover and land use data will be available online, at no cost. “We want thousands of eyes on land use and cover data. We want to help state and local partners with data on how we’re dealing with forests, flood plains, streams, and rivers. And we want an improved product that becomes the model for simulations of pollution control policies across the watershed.”

Scaling Up and Other Applications

As the technology is refined and used more widely by watershed partners, the Conservancy hopes to provide other data sets, scale up the work to other applications, and conduct annual or biannual updates so the maps reflect current conditions. “This data is important as a baseline, and we’ll be looking at the best way to be able to assess change over time,” says Allenby.

Watershed partners are discussing additional applications for one-meter-resolution data, from updating Emergency-911 maps, to protecting endangered species, to developing easements and purchasing land for conservation organizations. Beyond the Chesapeake, precision mapping could help conduct continental-scale projects. It offers the conservation parallel to precision agriculture, which helps determine, for example, where a bit of fertilizer in a specific place would do the most good for plants; the two combined could increase food production and reduce agriculture’s environmental impact. The technology could also help with more sustainable development practices, sea level rise, and resiliency.

Many people said it wasn’t feasible for a small nonprofit to do this kind of analysis, says Allenby, but his team was able to do it for a tenth of the cost of estimates. The bigger picture includes making land use and cover data available to the public for free. But that’s an expensive proposition at this point: The data needs backup, security, and a huge amount of storage space. Working with Esri, a Redlands, California-based company that sells GIS mapping tools, as well as Microsoft Research and Hexagon Geospatial, the Conservancy team is transferring the data. The process now runs linearly one square meter at a time. On a cloud-based system, it will run one square kilometer at a time and distribute to 1,000 different servers at once. Allenby says this could allow parcel-level mapping of the entire 8.8 million square kilometers of land in the United States in one month. Without this technology, 100 people would have to work for more than a year, at much greater cost, to produce the same dataset.

Precision mapping could bring greater depth to State of the Nation’s Land, an annual online journal of databases on land use and ownership that the Lincoln Institute is producing with PolicyMap. McCarthy suggests the technology might answer questions such as: Who owns America? How are we using land? How does ownership affect how land is used? How is it changing over time? What are the impacts of roads environmentally, economically, and socially? What changes after you build a road? How much prime agricultural land has been buried under suburban development? When does that begin to matter? How much land are we despoiling? What is happening to our water supply?