The Lincoln Institute provides a variety of early- and mid-career fellowship opportunities for researchers. In this series, we follow up with our fellows to learn more about their work.

A few years after earning her PhD in public policy from Harvard University, Jenny Schuetz participated in the Lincoln Institute Scholars program, which introduces early-career researchers to senior academics and journal editors. Schuetz now studies housing and land use policy as a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution; she’s also a lecturer in Georgetown University’s urban planning department, and the author of Fixer Upper: How to Repair America’s Broken Housing Systems.

In this interview, which has been edited for length and clarity, Schuetz discusses the ascent of zoning into the mainstream consciousness, the perplexing direction of climate migration in the United States, and how climate risk is threatening to upend the housing market.

JON GOREY: What was your experience with the Lincoln Scholars program?

JENNY SCHUETZ: When I did it, the focus was on matching up relatively early-career scholars with some of the experienced journal editors in the field and getting information on how you get your work into publications. How do you present it to an editor in a way that’s compelling, and work through the back and forth of the peer review process? And that was incredibly helpful, because it’s sort of a black box when you start out; you send off a paper, and you get back either a “revise and resubmit” or a rejection, but you often don’t really understand why. So getting to talk to some journal editors about what makes a compelling paper and how they think about pairing papers with reviewers was really useful.

I love that Lincoln does this. The cohort of junior people that I went through it with, we’re all now a little gray-haired and middle aged, but we still see each other. And it’s nice to see newer cohorts coming up through this. That’s a great way for the field to transfer knowledge and to help junior people grow.

JG: What have you been working on more recently, and what are you interested in working on next?

JS: A lot of my research still focuses on the role of zoning and land use regulations in restricting housing supply, and this has become a very hot topic in the last five or six years. One of the things that I’m actually doing now is working directly with state governments that are passing state level zoning reforms and trying to get those implemented and turned into more housing production. The implementation piece is really important—you don’t just write a policy and it implements itself, you have to have actual human beings doing things to implement it.

In fact, I’m just getting ready for a workshop in September with the Lincoln Institute, where we’re bringing together state housing agencies from seven or eight different states to talk to one another and share what kinds of challenges they’re running into, what kinds of successes. It’s a great chance for policymakers to talk to their peers in a way that they don’t often get to do, and we get to learn in real time what’s happening on the ground.

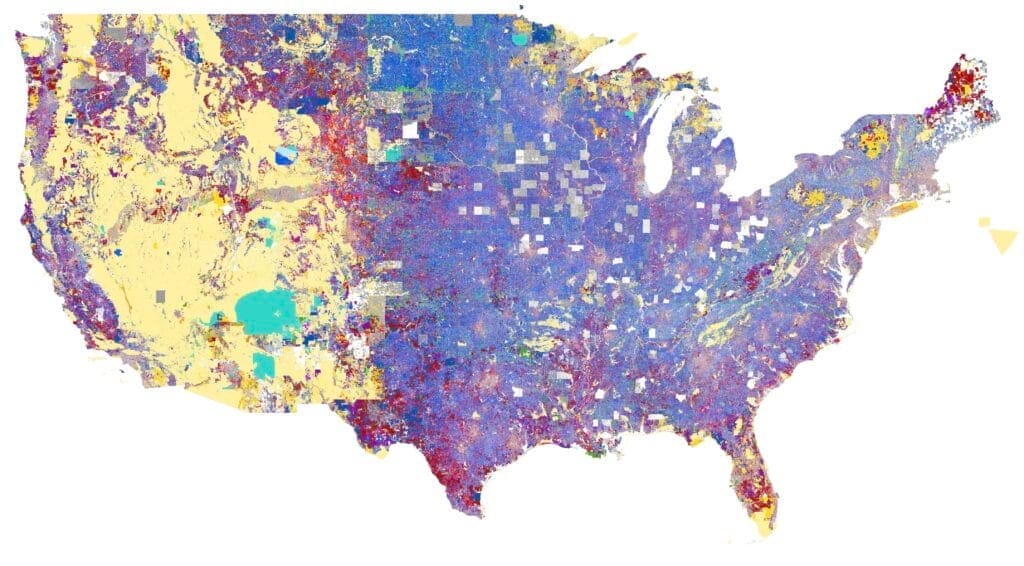

The second big piece of my research is looking at the intersection between housing and climate adaptation. There’s quite a bit of research coming out to show that, on average, Americans are moving toward more climate-risky places. We still have this movement away from the Northeast and Midwest toward the Sun Belt, so we are moving to places with extreme heat risk, drought risk, wildfire risk, and then people moving to Florida are moving into hurricane risk.

That’s going to have real repercussions for things like insurance markets, which are already seeing spiking premiums, and our national disaster recovery programs—we’re spending more and more money because we have more and more people and more expensive housing in these risky places. And we really don’t have a good handle on why people are doing this.

JG: What’s one of the most surprising things you’ve learned in your research?

JS: That people are overwhelmingly moving toward risky places at a time when disasters are becoming more and more salient and expensive is counterintuitive. And the reasons for it are complicated. Some of it is people don’t know what it’s like to live in 115 degrees until they move there, or people are overly optimistic [about their exposure to hurricane risk].

But also our policies aren’t designed to send the right market signals. It should be a lot more expensive to buy a house and take on a mortgage and buy insurance in places that are really risky—but our policies don’t allow that to happen, because we’re trying to keep homeownership affordable for middle-income Americans. We want everybody to buy a house and invest in it, and so we have to make it artificially cheap for people to do that, and then it encourages people to buy in the wrong places.

JG: What do you wish more people out there knew about housing?

JS: One of my longstanding beefs has been that the US leans very heavily on homeownership for wealth building. And as a motivation for that, we have not provided good standards of living and protection for renters, and have made renting seem like it’s a second-class option—that you’re a renter only until you can afford to become a homeowner. I think that has led to a lot of subtle discrimination against renters, and a lot of people not taking seriously that we need to make renting a good option.

Most of us will be renters at some point in our lives. We should just make renting a reasonable option for middle-class households for as long as it suits their needs—that should be an okay option for people at all ages and stages of their life.

JG: When it comes to your work, what keeps you up at night? And what gives you hope?

JS: The climate stuff keeps me up at night. One of the chapters in my book was about climate, and I read a lot more than I had previously on this stuff and decided, wow—this needs to be a major focus of my research, because it’s so big and important and it’s not being talked about in productive ways that get us to better policies.

On the optimistic side, there are two things. One is that we are having a lot more national public conversations about housing, whether that’s affordability or insurance premiums. I mean, zoning never got mentioned in broader media discussions or in presidential elections until four years ago, and now it’s on the front page of the newspaper a lot. So I think a broader understanding of some of the problems is really helpful for starting to move forward.

And there is so much policy experimentation and energy at the state and local level, so many cities and states that are trying new things. We’ve done the same thing with our land use for 70 or 80 years, and now suddenly we’re trying new stuff, which is great. There’s a lot of grassroots energy, and much of this is coming from younger households—which are really motivated to fix this problem—and they are getting engaged with local politics in constructive ways, trying to push their local elected officials to do better. So the kids give me hope.

JG: You’ve written at length about accessory dwelling units (ADUs), among other things, and now several states have essentially legalized ADUs statewide. What does it feel like when a policy or idea you’ve written about extensively gets adopted at a high level?

JS: It’s pretty rare that you can see your idea directly show up in policy—policymakers talk to a lot of experts, and they get a lot of opinions thrown at them, so it’s often very hard to trace your immediate impact. But it’s exciting to see ideas take shape. Both to see them translated into policy, but I think, equally, to hear people start talking about them in the ways that we’re framing the problem. I like to say we’ve got two affordability problems: the lack of supply and poor households not earning enough. And that framing has gotten picked up in a lot of places, and they’re talking about it in a more constructive way.

JG: What’s the best book you’ve read lately, or a show you’ve been streaming?

JS: I’ve been reading a lot of books about climate and housing, and they’re really depressing. I’ve been streaming “Killing Eve”—I was late to the party on that one—but that’s just fun and escapist. I love spy stories and mystery stories, and that’s a good one. It actually makes me feel like real life is okay, because there aren’t spies lurking in every corner ready to kill me!

Jon Gorey is a staff writer at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Lead image: Jenny Schuetz of the Brookings Institution testifies before the US Congress Joint Economic Committee about expanding the supply of affordable housing. Credit: Courtesy of Jenny Schuetz.